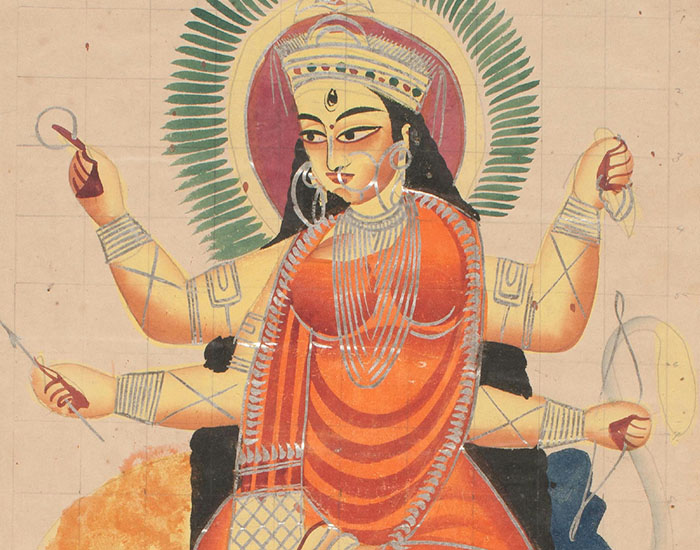

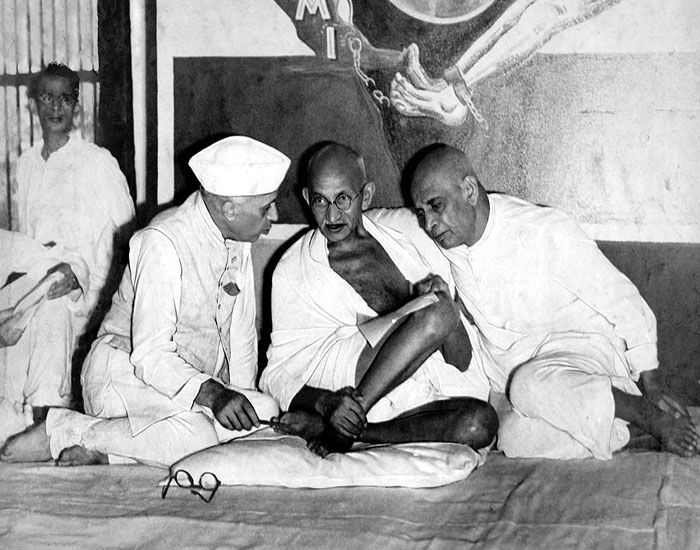

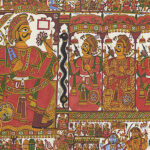

Known for their intricacy and small scale, miniature paintings in medieval India were composed into personal albums (or muraqqas) and manuscripts where they illustrated the accompanying text. Such manuscripts largely consisted of romances, epics, works of fantasy, travel literature, religious texts and biographies.

The tradition of miniature painting in the Indian subcontinent has been traced to palm leaf manuscripts made in the ninth century under Pala patronage in eastern India and Nepal. From the eleventh century onwards, Jain manuscript painting began to be practised in the west and central India, first on palm leaf and then, with the introduction of paper from West Asia in the fourteenth century, in large paper codices as well. These palm leaf paintings had a limited but bold colour palette and used innovative compositions to pair the text with images.

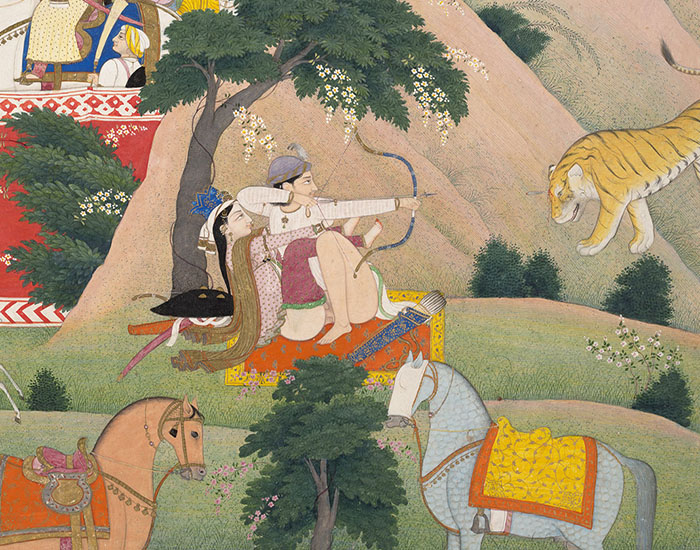

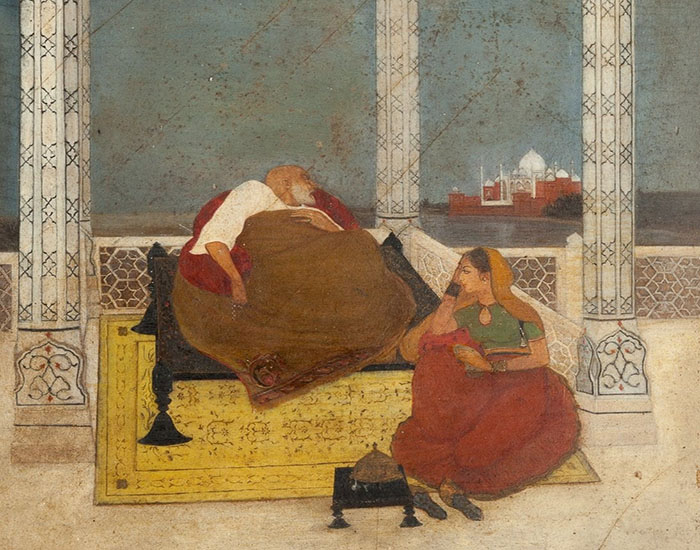

The painting style of the Safavid court in Persia exerted a heavy influence on Mughal and Deccan miniature painting in the late sixteenth century. Mughal painting was especially influential due to the empire’s political power, and this naturalistic, restrained and yet heavily ornamented style was often imitated by smaller kingdoms. Rajasthani, Deccan, Maratha and Pahari courts often employed artists who had trained in the Mughal style, although these schools eventually came to be known for their own unique styles, techniques and subject matter.

ARTICLE

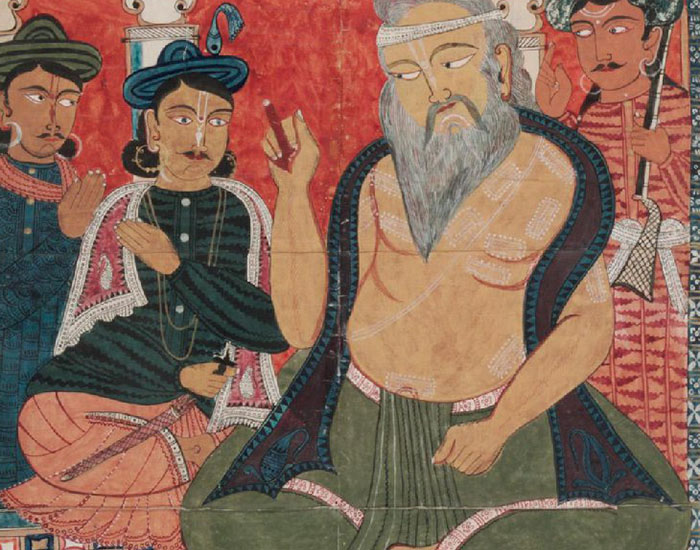

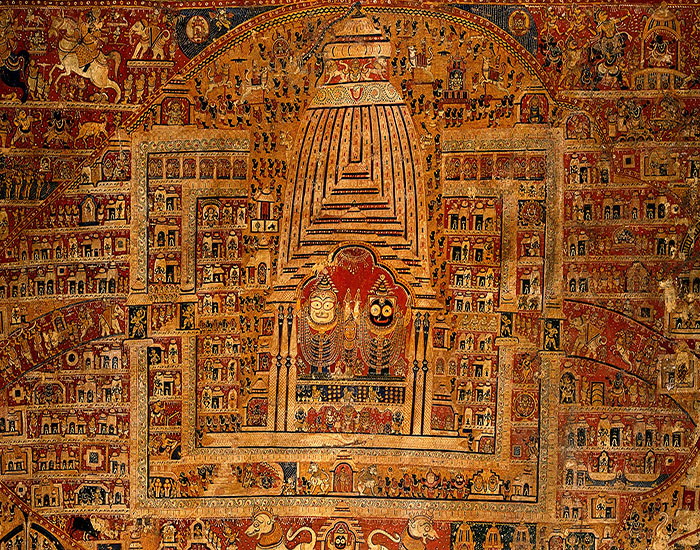

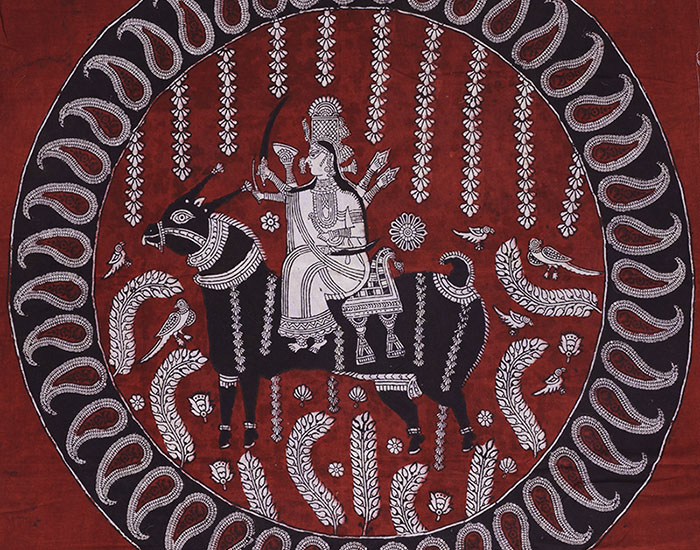

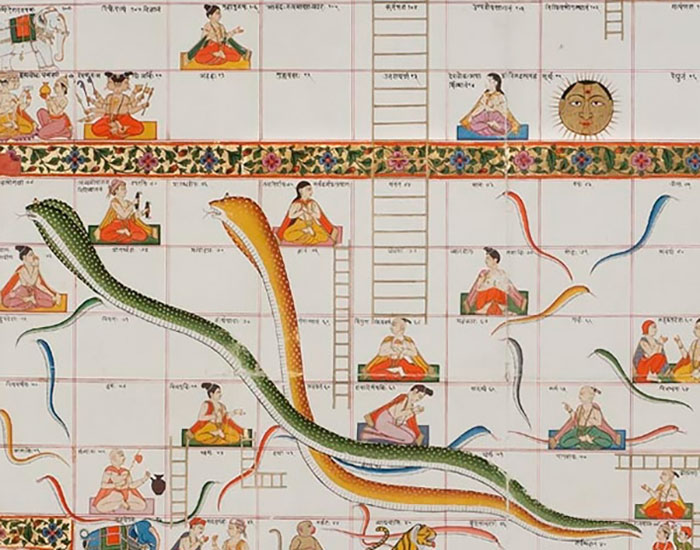

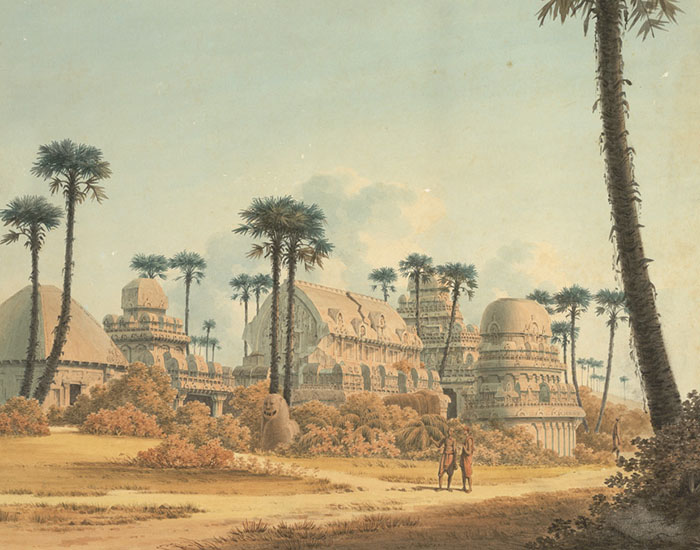

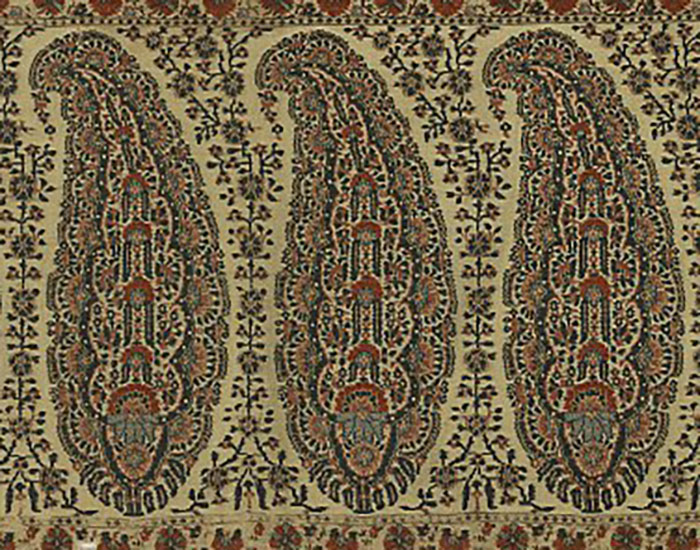

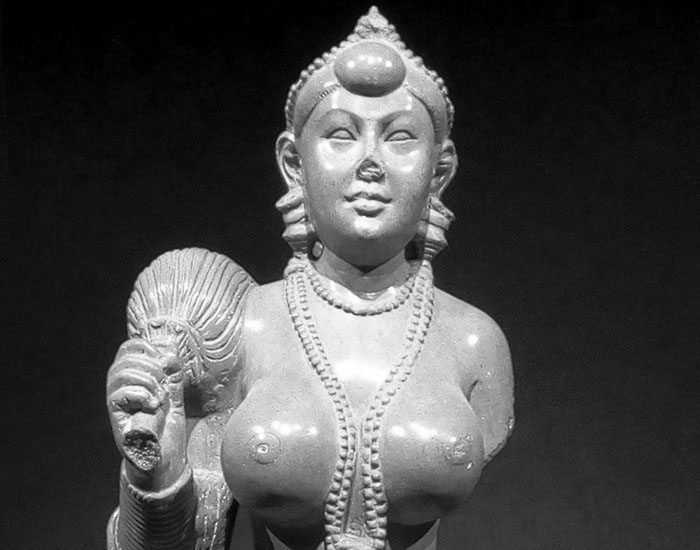

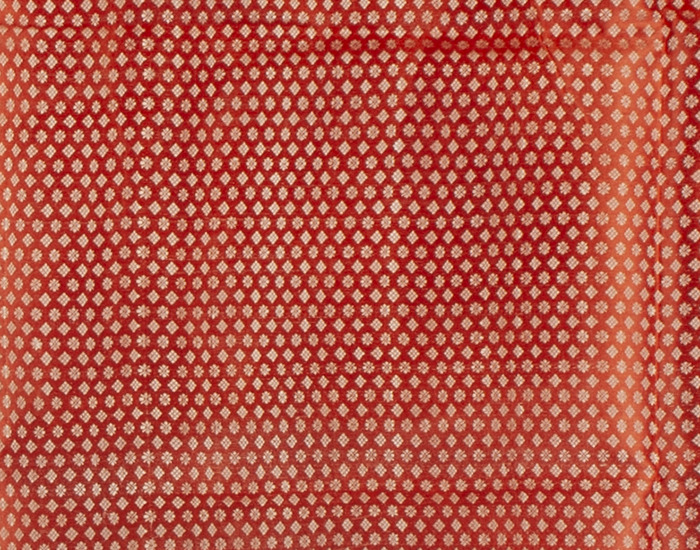

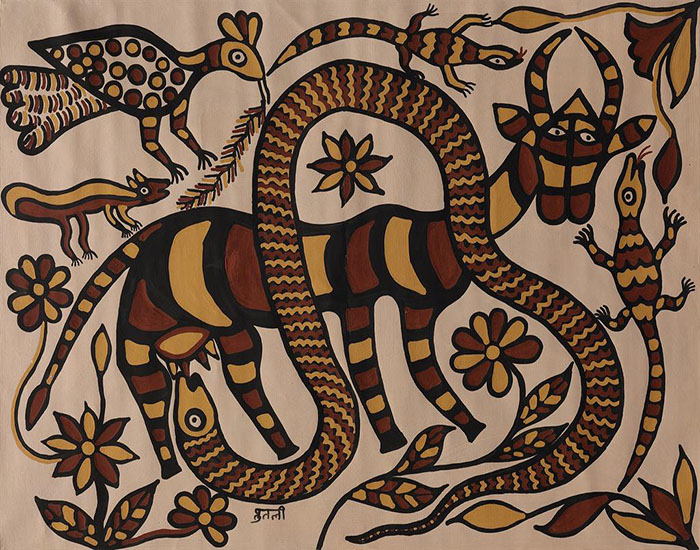

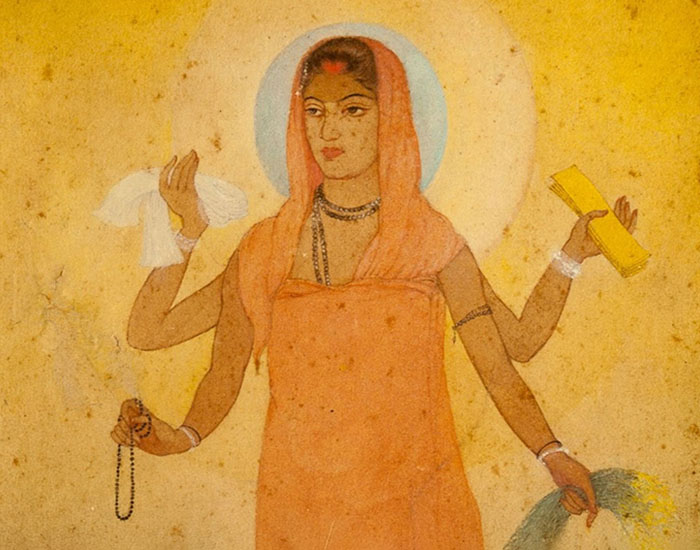

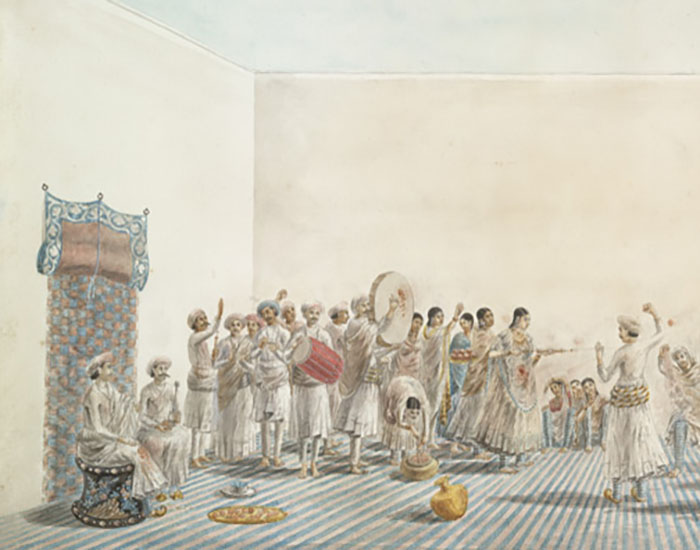

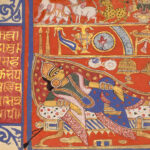

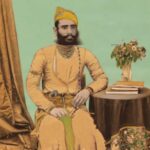

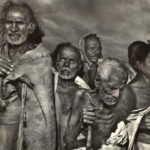

Comprising the manuscript illustration traditions patronised by the sultanates of Ahmadnagar, Bijapur and Golconda, Deccani manuscript painting flourished between the sixteenth and late seventeenth centuries. It also includes the manuscripts and muraqqas commissioned by Maratha emperors and peshwas in the eighteenth century, though these were fewer in number. Manuscript painting in the Deccan grew steadily until the Mughal conquest of the region between 1600–87 resulted in the annexation of the Deccan sultanates, after which a combination of puppet governments and appointed governors kept the practice alive, but with a heavy emphasis on emulating the Mughal aesthetic. The Deccan plateau, which extends over most of the land between the eastern and western coasts of the Indian peninsula, has enjoyed a long history of trade and artistic exchange because of its many ports, which linked it to the Indian Ocean trade routes. Further, the royal families of several Deccan sultanates also had ancestral or cultural links with Persia and Turkey. As a result, Deccan manuscript painting absorbed a range of influences, especially from the Safavid and Mughal ateliers, and, in its initial phases, from the paintings and sculptures of medieval Hindu and Jain temples in the region. It is also notable for its patronage from women rulers, whose power is reflected in the paintings, as well as in subjects such as astrological charts, the Buraq and composite animals. While the style varied somewhat between courts and time periods, overall Deccani manuscript paintings were boldly coloured, heavily ornamented, and often equal parts fantastical and detailed in their rendering of flora and fauna. The costumes and jewellery worn by the figures featured varying degrees of synthesis between the south Indian fashions of the time and the traditional attires of Persia and Asia Minor. The matured styles of the various courts — in the early decades of the seventeenth century — show a fascination with movement, especially the suggestion of a slight breeze that lent a characteristic dynamism to otherwise static figures. Persian influences can be seen particularly in the way mountains and faces were drawn, and in the high, slightly curved horizon line. However, as Mughal military expansion into the south began at the end of the sixteenth century, painters began to move between Mughal and Deccan ateliers, sometimes deliberately altering their work for their north Indian patrons. Over time, Deccani paintings became more naturalistic, more tightly composed and more muted in their colour choices – similar to the Mughal style. The oldest surviving manuscript paintings from the region belong to the incomplete Tarif-i-Hussain Shahi manuscript, made in 1565 for the Ahmadnagar court, though scholars speculate that there may have been older manuscripts that are now lost. Information on the development of the Ahmadnagar style is particularly fragmentary, as few folios and drawings have survived. The prominent position given to Khanzada Humayun, the queen regent of Ahmadnagar between 1565–69, in the paintings and the text of the Tarif-i-Hussain Shahi manuscript suggests that she likely commissioned it herself. However, she was deliberately erased later on in all but one painting of the manuscript after her son Murtaza overthrew and imprisoned her. The Ahmadnagar style appears to become more restrained and naturalistic in the 1570s, and a clear Mughal influence is visible by the 1590s. By 1600, however, political turbulence in the kingdom and the Mughal conquest of key cities in Ahmadnagar ended local patronage for the art form, although Rajput governors of the Mughal Deccan continued to hire artisans for Rajasthani-style miniatures, particularly for portraits and ragamala paintings. The Bijapur sultanate, also formed in 1490, extensively patronised manuscript painting. The earliest example is the Nujum-ul-Ulum, an encyclopaedic manuscript on astrology and magic commissioned by Ali Adil Shah I. His successor, Ibrahim Adil Shah II, sponsored manuscript painting and other art forms generously, also dabbling in painting himself. His reign marks what scholars consider the high point of Bijapur painting, which is notable for its extremely dense use of golden floral and arabesque patterns for the ornamentation of clothing, and its intricate, varied depiction of flora. Ibrahim’s interest in both Hindu mythology and Sufism allowed for the inclusion of syncretic symbolism in illustrations commissioned during his reign, and even more so in the accompanying texts. Chand Bibi, aunt and queen regent during Ibrahim’s minority, features in later eighteenth-century Deccan paintings as the ideal female ruler and warrior, typically depicted hawking with an entourage. While Ibrahim’s successors continued to commission illustrated manuscripts, this was done as a matter of courtly duty rather than personal interest. This, along with the increased presence of Mughal governors in the region following the conquest of Ahmadnagar territories in 1600–36, meant that the younger generation of local artists was encouraged to emulate the Mughal style in their commissioned manuscripts. Many artists trained in the north were also brought into the royal ateliers of the Deccan. As a result, the Bijapuri style became very close to that of Mughal manuscript paintings by 1680, soon after which Bijapur was annexed by Aurangzeb. Meanwhile, in the north Deccan, the Maratha court took an interest in manuscript painting, commissioning muraqqas, ragamalas and illustrated copies of religious texts regularly over the course of the early seventeenth and eighteenth century. Initially, these were made at Rajput kingdoms in Rajasthan, but as Maratha patronage steadied, local painters were hired in the chitrashalas or painting ateliers at Poona (now Pune). In Hyderabad, the Qutub Shahis of Golconda – the wealthiest of the Deccan sultanates – employed local, West Asian and Central Asian artists in their atelier, but the style tended towards that of the Safavids. While the idealised faces and bodies of human figures of these paintings are characteristic of Persian painting, their realistic postures suggest the hand of local artisans experienced in making stone sculptures for temple walls. The Golconda style underwent subtle changes over the course of the seventeenth century: first, in the form of the Mughal naturalism, which had already spread to Bijapur, and then as a deliberate rigidity and restraint seen in painted figures, possibly in emulation of new Persian painters of miniatures such as Shaikh Abbasi. Scholars have suggested that this style may be the work of Deccani artists who trained in Persian ateliers and returned to India or of Persian artists migrating to India themselves. Following the capture of Golconda by Mughal forces in 1687 and the deposition of the Qutub Shahis, a Mughal tributary state based in Hyderabad emerged as the major political presence in the south Deccan in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. While these rulers were governors and not royalty, they still functioned as major patrons, typically commissioning portraits in which they appear in profile with grave expressions, possibly to emulate the Mughal style – a choice that was somewhat undercut by the abundant flora surrounding them. After Hyderabad and the southern Deccan were taken over by the Asaf Jahis in 1724, the court style retained its rigid emulation of Mughal painting, steadily sponsoring artisans over the course of the eighteenth century. These works were technically well-executed and extremely formal, with the dynamism and nuance of earlier Deccan styles visible only in drawings and sketches. Today, folios and manuscripts illustrated in the Deccan can be found in museums and private collections across the world, including the National Museum, New Delhi; the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhak Mandal, Pune; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA; the David Collection, Copenhagen, Denmark; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, USA; and the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts, St. Petersburg, Russia.

ARTICLE

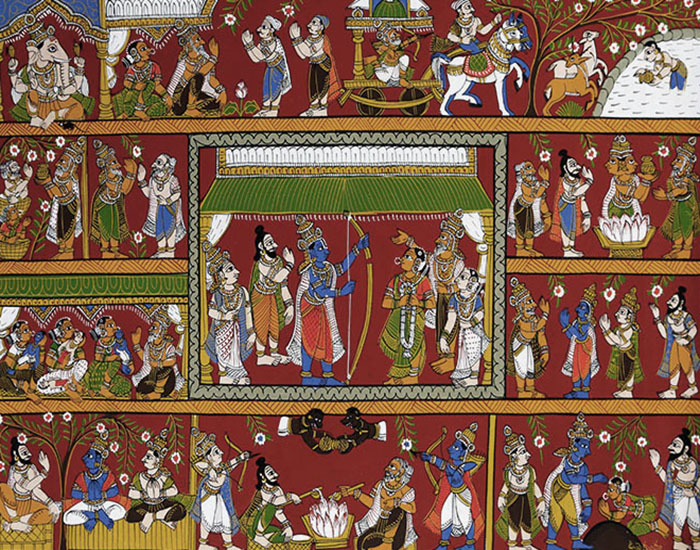

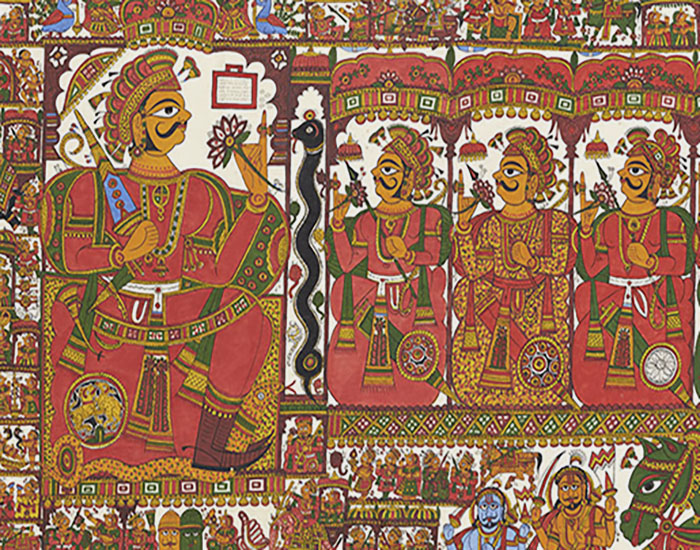

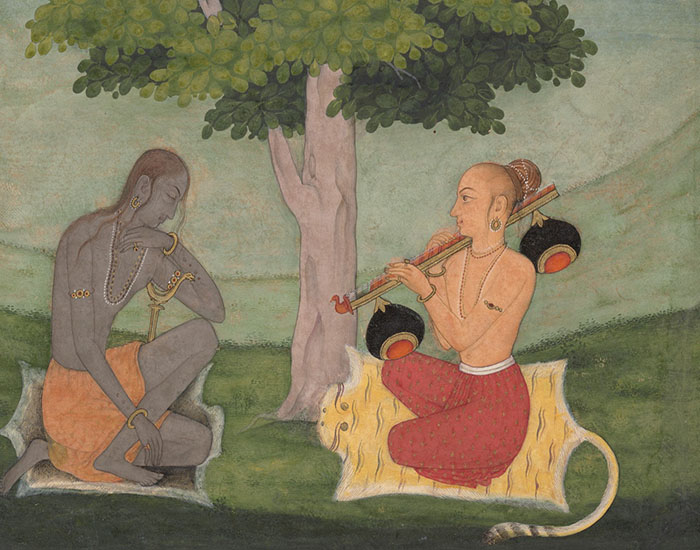

The traditions of manuscript painting that emerged in the Rajput courts of central and northwestern India between the sixteenth and the eighteenth century are collectively referred to as Rajasthani manuscript painting. Imbibing elements of naturalism, as well as Mughal and Islamic influences, these paintings were characterised by flat compositions, the use of black outlines, pointed facial features and a bold colour palette. The earliest examples of painted narratives from the region – which comprises the present-day states of Gujarat and Rajasthan – are the palm leaf manuscripts of Jain texts, which were stored in bhandaras, or libraries. By the fifteenth century, secular and Hindu religious manuscripts also began to appear, including illustrated versions of the Gita Govinda, the Devi Mahatmya, the Panchatantra and the Rati Rahasya. Despite their use of paper, these texts retained the restricted, horizontal format of palm leaf manuscripts. The illustrations themselves are characteristic of the Western Indian style of painting, featuring saturated colours, angular silhouettes, protruding almond-shaped eyes and faces depicted in three-quarter profile. By the mid-fifteenth century, a stylistic shift was precipitated by the growing influence of Persian and Islamic court art, with Jain manuscript paintings from this period incorporating elements such as decorative borders as well as embellishments like silver, gold and lapis lazuli. An illustrated Bhagavata Purana from this period also reflects the influence of Islamic codexes, with images becoming independent of text and expanding in size, sometimes occupying the entire folio. Another significant evolution was the development of an early Rajasthani style, also known as the Chaurapanchasika style, which derived its name from a group of sixteenth-century poetry manuscripts. During the Mughal era, Rajasthani manuscript painting developed in the Rajput courts of the region, in workshops that were likely inspired by their Mughal counterparts. The Mughal techniques of naturalism in landscape and physiognomy, spatial depth and perspective, were absorbed to differing degrees in these courts and co-existed alongside their own traditional styles. The themes of the manuscripts from this period were diverse, encompassing religious texts such as the Bhagavata Purana, epics such as the Ramayana and Mahabharata, as well as legends and stories about local folk heroes. Works about the life of Krishna, in particular, were popular and produced across the different royal courts. Poetical works such as Rasamanjari, Rasikapriya were also commissioned, as were devotional works like the Gitagovinda and Sur Sagar. Each Rajput court across the region had its own legacy and style of manuscript painting. These were not always limited to royal workshops. In Marwar, for example, a Meghaduta manuscript was commissioned by lay patrons in 1699 and was stylistically similar to a traditional Ragamala series dating back to 1624. At Mewar, which was another prominent school of miniature painting, the earliest manuscript, Chawand Ragamala, dates back to 1605. It is one of several notable works produced by the court’s workshop during the first half of the seventeenth century, including the Mewar Ramayana (1649–53). The central Indian region of Malwa already had a longstanding manuscript painting tradition, now known as the Malwa school of painting. After the fall of its capital, Mandu, in the second half of the sixteenth century, the smaller Rajput principalities of the region kept its tradition of illustrated manuscripts alive. In the seventeenth century, the style of the Bikaner school continued to parallel the Mughal artistic style of the time. However, by the second half of the century, the Mughal workshops suffered a decline and its local painting tradition re-emerged and gained prominence, as evidenced by a Rasikapriya series and Bhagavata Purana dating to this time. During the same period, manuscript painting was also flourishing in the workshops or chitrashalas of Bundi and Kota. The former is notable for its use of elements from both the Mughal and the Deccani schools. The latter, after its separation from Bundi, established its own painting tradition, which included detailed depictions of landscapes and hunting scenes in addition to devotional works. The apogee of the Kishangarh school, meanwhile, came in the first half of the eighteenth century, characterised by devotional paintings of Radha and Krishna. These paintings, primarily executed by the master artist Nihal Chand, were based on the Bhagavata Purana, the Gita Govinda and the poems of Savant Singh, the then ruler of Kishangarh. In the court of Amber at Jaipur as well, court painting gained prominence in the eighteenth century, with several manuscripts produced under the royal patronage of its ruler Savai Pratap Singh, including a Ragamala series and a Rasikapriya series. Like many manuscript painting traditions in the subcontinent, the administrative and economic policies of the British Crown in the nineteenth century led to a decline in patronage as the wealth of most smaller courts was reduced. Coupled with the arrival of photography, which attracted the interest of royal patrons, and new forms of employment for artists, such as Company Painting, Rajasthani and other miniature painting traditions faded away by the late nineteenth century.

ARTICLE

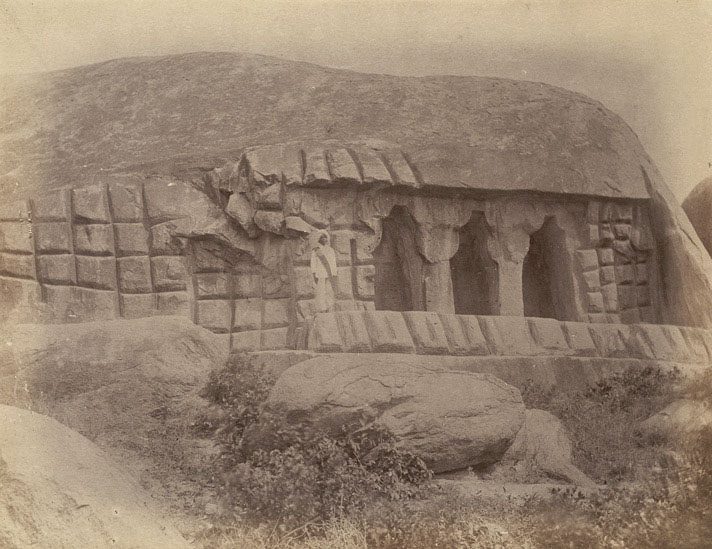

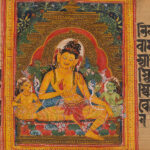

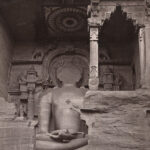

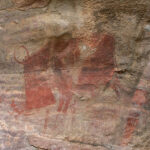

Bound and painted palm-leaf books commissioned during the reign of the Pala Dynasty, illustrated manuscripts were a significant aesthetic mode in early mediaeval Bengal, along with bronze and stone sculptures and architecture. Through this period, the modern-day regions of Bihar, West Bengal and Bangladesh became possibly one of the last major sites for disseminating Buddhism in South Asia and beyond between the ninth and thirteenth centuries CE. Illustrated manuscripts from the period were thus informed by various aspects of Buddhist iconography and sacred textual traditions, such as the Ashtasahasrika Prajnaparamita (The Perfection of Wisdom in Eight Thousand Lines) or episodes from the Jataka tales. While they owed the evolution of their artistic style to previous models like the Ajanta cave and mural paintings of the time, they also marked new ways of developing the miniature painting tradition in the Indian subcontinent. Apart from sites occupied by the Pala Dynasty, especially centring on Nalanda and Kurkihar, and the Varman Dynasty to its east, similar illustrated manuscripts have been found in places like Nepal, Tibet and Southeast Asian states like modern-day Burma and Thailand, possibly taken there by Buddhist monks and scholars. Many of these manuscripts were found with thickly daubed layers of vermillion, sandalwood paste, oil and milk on the covers, suggesting that they were considered to be personal objects of devotion and worship rather than books to be read for leisure. Talipot palm leaves were used for these manuscripts, cut to sizes about five or eight centimetres wide and fifty to fifty-five centimetres in length, smoothened with a stone and primed with a thin layer of white. They were strung together with cords and usually bound within varnished wooden boards, although in some cases ivory or copper was used. The text was inscribed on the palm leaves with a careful kutila (“hooked”) script and gaps were left for the paintings to be filled in later, usually in oblong spaces of 5.5 centimetre x 7.5 centimetre area. Most manuscripts tended not to have illustrations, and when they did they were arranged usually in groups of three to a page: placed either at the beginning, the middle of the text or at the end. Black or red outlines were usually sketched first to give the figures a marked lineament. These were usually filled in with solid colours, although some mixing of the organic colours could be seen in depictions of skin textures. The colours were derived from mineral sources and followed a process of extraction and grinding that was similar to the one employed for the Ajanta paintings. Typical colours included white, yellow, blue, vermilion, green and black. The colour schemes and iconographies were defined by sacred texts and practices in the Buddhist monasteries where they were made. Red ochre was used to make the final sketch, while black was applied to define the eyes and features of the face. While early instances of manuscript paintings show multiple figures somewhat crowding within the frame, later examples showed a more relaxed approach to composition, with flowing lines and increased plasticity in the figures, especially in contrast with sculptural works. Tonally flat colours were used for backgrounds, with figures fixed on singular planes. Faces were usually depicted in three-quarter views, although the Buddha was presented frontally. The roundness and volume of the figures were usually highlighted with transparent applications of dark tones of colour on the outlines. Scholars have argued that the tradition of manuscript illustration saw at least two variations within the style, loosely defined by their locations in the north or south of Bengal and Bihar. The former was also known as the “Varendra” style and was situated in the Magadhan centres of modern-day Bihar, such as Nalanda. Illustrations executed in this style usually bore hard lines and ornate compositions. Sometimes, figures of donors or patrons and their family members were painted directly onto the manuscript, usually just beyond the central frames of the main illustration. Archaeological sites in the Munshiganj district in modern-day Bangladesh, dating to the eleventh–twelfth centuries CE, led to the recovery of two manuscripts in the southern style, also known as the “Vanga” style. One features the complete text of the Ashtasahasrika Prajnaparamita and the other one a set of twenty-two illustrated folios of the same text in another, incomplete manuscript set, now lodged at the Baroda Museum and Picture Gallery in India. The southern style is marked for the simplicity of its pictorial style, minimal decorations and bold application of tonally flat colours. The manuscripts were written in a proto-Bengali Gaudiya script, rather than the kutila script preferred in the north. Many manuscript painting workshops in the region were disrupted towards the end of the twelfth century, when Turkic rulers began to establish their rule over present-day West Bengal, Bangladesh and parts of Bihar. The Bharat Kala Bhavan and The Asiatic Society of Bengal hold some Pala manuscripts, particularly of the Prajnaparamita Sutra, dating back to the eleventh and twelfth centuries CE.

ARTICLE

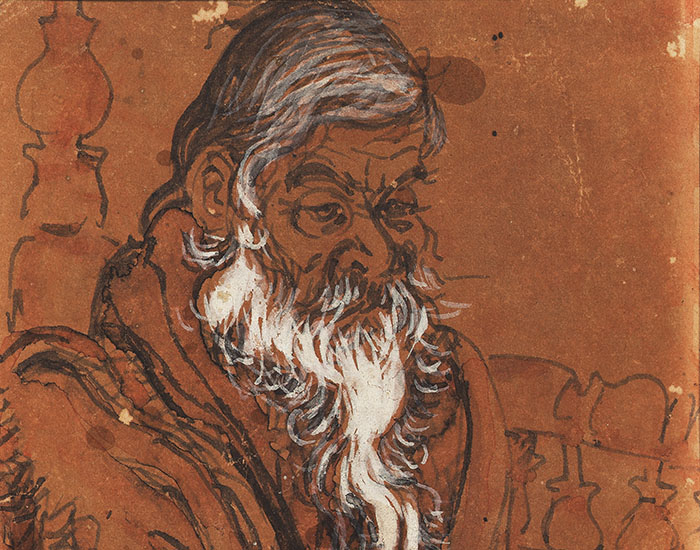

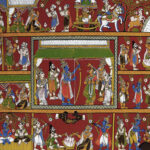

Manuscript and muraqqa illustration traditions in kingdoms at the foothills of the Himalayas — including present-day Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, and Jammu and Kashmir — are grouped together under the term pahari, meaning “of the mountains.” These kingdoms were established by Rajput kings from Rajasthan in the late seventeenth century and maintained their sovereignty until the early nineteenth century. The courts at Basohli, Kulu, Guler and Kangra in particular took great interest in manuscript painting and established the careers of notable artists such as Pandit Seu and his sons, Nainsukh and Manaku, to whom the distinctive character of Pahari painting is largely credited. Manuscript painting flourished in the Himalayan foothills – which are also known as the Punjab hills as they pass through the northern part of Indian and Pakistani Punjab – until these kingdoms were annexed by the Sikh Empire and the British East India Company in the first half of the nineteenth century. Despite major changes and external influences, Pahari painting retained certain key features. The paintings usually illustrated amorous or religious Hindu texts, particularly those featuring Krishna and Radha, namely the Gita Govinda and Bhagavata Purana. To a lesser extent, the Nala-Damayanti, Mahabharata and Ramayana were also illustrated. Following Rajput tradition, Pahari courts also commissioned ragamala albums and portraits of young kings. Almost all figures – in albums as well as in manuscripts – were depicted in profile, with their facial features rendered with increasing accuracy over the eighteenth century. Costumes were carefully painted to convey their pattern and texture. While Pahari painting is often divided into a Basohli and Kangra phase due to the heightened influence of these courts, manuscripts and albums were commissioned by many other kingdoms in the region, albeit for smaller projects and sums of money. The artists hired for these commissions worked throughout the region, as a result of which it is difficult to distinguish variations of styles across different courts. The earliest manuscript from the Himalayan foothills is an illustrated copy of the Rasamanjari, made at Basohli between 1660 and 1670. This early style is characterised by the use of bright, deep shades of yellow, ochre and green; detailed depictions of ornamentation on the main figures of the painting; and the use of strong gestures to express heightened emotions. The almond-shaped eyes are wide open and intense, especially in romantic or intimate scenes. While necessary details of the environment were painted around the characters — such as trees or architectural features — these were kept in the middle ground or foreground, while the background was usually a solid colour field with a very high horizon line. When noble or royal persons were included in a painting, they were often shown to be disproportionately large compared to the structures inside which they were situated, underscoring their importance in relation to other figures. For a brief time, paintings at Basohli in the seventeenth century included the application of wing cases from beetles on the figures’ costumes to imitate jewellery. However, this technique is not seen in later paintings. As a result of the political independence and the remoteness of the Pahari kingdoms, the early Pahari style at Basohli was far removed from the naturalism, restraint and muted colours of Mughal painting, despite the strong influence of the Mughal style in Rajasthan and the Deccan during the same period. Over the course of the next century, however, Nainsukh began to occasionally work for the Rajasthani and Mughal courts and, as a highly influential painter, became responsible for the introduction of Mughal elements into the manuscripts painted in Basohli and surrounding kingdoms. Additional Mughal influences on the Pahari style were brought by the many artisans who fled from the atelier of Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah, following the seige on Delhi by Nader Shah’s forces in 1739. Notable features that distinguish this later style from that of the seventeenth century include a landscape backdrop with a lower horizon line, a lighter colour palette, less ornamentation in the costumes, and a more realistic size difference between human figures and architectural elements. This style, established in the mid to late eighteenth century, is considered to be the fully realised form of Pahari painting. The Kangra ateliers flourished in the late eighteenth century to the early nineteenth, carrying forward the themes, experiments and Mughal influences of the Basohli paintings, while also adding new elements. This was largely done by artists from the families of Nainsukh and Manaku, under the patronage of the Kangra king Sansar Chand. In addition to the features of the late Pahari style described above, Kangra paintings feature an emphasis on the green, undulating landscape of the Punjab hills as well as a continuous narrative technique practised mainly in Pahari paintings and very rarely in Rajasthani and Mughal ateliers. This composition technique typically involves the strategic arrangement of trees and architectural elements in such a way that a scene is divided into panels. The main participants of the narrative are shown multiple times in the same painting, enacting different parts of the narrative within the divisions created by the surrounding landscape and buildings. Continuous narratives were usually applied to known stories from the Bhagavata Purana, the Gita Govinda and the Ramayana, possibly so that the painting would remain intelligible to the viewer. Royal patronage for Pahari manuscript painting ceased in the early nineteenth century, prompting many Pahari artisans to take up employment at Sikh or Rajasthani courts. While some minor artists in Kangra continued to practice the art form, the Punjab hills were no longer a cultural centre for most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Today, organisations such as the Kangra Arts Promotion Society (KAPS) and the Kangra Museum of Arts in Dharamshala offer training in the traditional Pahari style of painting, including the use of traditional materials and pigments. These paintings are sold commercially as individual works, although the income from sales and the stipend from these organisations remain a precarious form of livelihood for traditional Pahari artists.

ARTICLE

A major tradition of miniature painting in the history of South Asia and the wider Islamic world, Mughal manuscript painting emerged in the mid-sixteenth century in the royal ateliers (workshops) of the Mughal kings and remained highly influential until the late eighteenth century, well after the decline of its foremost patron, the Mughal court. Known for its naturalism, intricacy, luminosity and pluralism in both style and subject matter, Mughal miniature painting embodied a range of syncretic influences. Borrowing from styles as diverse as Persian miniatures, pre-existing manuscript paintings in South Asia and European Renaissance images, these paintings served as historical documents, visual aids for storytellers, illustrations for significant literary texts, ritual objects and accompanied scriptures and scientific literature. Inspired by the aesthetic achievements of Shah Tahmasp’s court in Safavid Persia (present-day Iran), the Mughal emperor Humayun had successfully negotiated to take two Persian artists, Mir Sayyid Ali and Abd al-Samad, with him to India, along with military aid. In 1555, Ali and al-Samad set up the Mughal atelier after Humayun re-established the Mughal empire in India. As Mughal power and influence grew in the subcontinent, so did the painting style’s popularity and aspirational value for many smaller courts in South Asia. As a result of this, contemporary scholars categorise Mughal manuscript paintings into two distinct categories — the imperial Mughal painting that was executed by the Mughal atelier and commissioned by the court, and a sub-imperial or popular form of Mughal painting, which was made by other, smaller ateliers without royal patronage. The difference is visible in the subject matter, intricacy and naturalism of the style, and the quality of materials used, while the similarities result from the standards set by the older and more lauded imperial atelier. During Akbar’s reign — which came shortly after the Mughal atelier was set up — the size of the royal atelier grew from about thirty artists in 1557 to over a hundred in the 1590s and consisted of painters, colourists, calligraphers, bookbinders and other specialists. Mughal manuscript painting, sponsored as it was by the wealthy Mughal court, used fine quality paper which was imported from Persia and Italy. Pigments for colours were derived from similarly rare and expensive mineral sources such as lapis lazuli, orpiment, cinnabar and gold, amongst others. Illustrated manuscripts were often commissioned from texts of classical Persian literature, biographies of Mughal rulers and their ancestors, historical documents and Persian translations of works of ancient Indian literature. Illustrations of key scenes would appear alongside the calligraphic nastaliq text. Additionally, in order to efficiently carry out a large number of projects — including illustrated manuscripts, individual paintings and designs for other objects — the hierarchy within the atelier remained somewhat fluid but highly collaborative. Within a given folio a master painter composed the image based on the text, which would then be coloured in by a junior artist. Further, there were some artists who specialised in portraiture or drawing animals. This achieved a level of consistency amongst different artists, but also maintained an individualistic style. For example, the artist Daswanth became well-known for his fantastical and frenzied compositions that stood in direct contrast to the work of Basawan, a contemporary, who became well-known for his talent for naturalism. Occasionally, the individual folios in the manuscripts also contained copious details such as the names of the artists involved, number of days taken to complete the artwork, the size of the atelier and so forth. One of the earliest examples of illustrated manuscripts from this period is the *Tutinama (‘Tales of a Parrot’), which was written in the fourteenth century and illustrated in the 1560s. It displays indigenous flora and fauna within Persianate landscapes and includes the realistically proportioned dark-skinned figures associated with South Asia, rather than the willowy, fair-skinned youths emblematic of Persian paintings. Mughal artists were also introduced to European influences around this time, when European emissaries and missionaries brought religious paraphernalia and examples of European art with them to the Indian subcontinent. This infused notions of pictorial depth and perspective into the sensibilities of the artists, though this always remained a minor component of the fully formed style of Mughal painting. Thus, the Mughal style of painting is characterised by the amalgamation of Persian, Indian and European styles. Apart from the Tutinama, some other important manuscripts that represent the Mughal manuscript painting tradition include — the Hamzanama (‘Book of Hamza’), a fictional biography of the prophet Mohammed’s uncle Hamza ibn Abdul-Muttalib (c. 569–625), made during Akbar’s reign and considered to be one the largest and most ambitious manuscripts illustrated by the atelier with its 1400 paintings; the Akbarnama (‘Book of Akbar’), a real-time documentation of Akbar’s reign, illustrated by at least forty-nine artists in the atelier; Shah Jahan’s biography, the Padshahnama (‘Book of the Ruler of the World’), known for its use of multiple perspectives and exuberant colours; and the Khamsa of Nizami, a collection of five poems from Nizami Ganjavi (c. fourteenth century), again produced in Akbar’s court. Over time, the structure of the atelier and the types of manuscripts being produced changed. In the 1580s and 1590s, the atelier mainly worked on dynastic histories such as the Timurnama (‘Book of Timur’, written in the sixteenth century) or the Baburnama (‘Book of Babur’, written in the fifteenth century), and translations of Hindu epics such as the Mahabharata (known as the Razmnama). These would often be large projects, both in the dimensions of the codices as well as the number of illustrations commissioned. In comparison, Persian poetical texts were much smaller in size and were worked on by fewer artists. During the reign of Jahangir, the focus moved away from manuscripts to muraqqas — albums of miniature paintings and calligraphic manuscripts — and the number of artists retained by the imperial atelier for long-term projects was significantly reduced because of the emperor’s tastes and interest in the works of only a few individual artists. Stylistically, Jahangir preferred naturalism and favoured elements of Persian painting along with a particular emphasis on portraiture. Flourishing under the patronage of Akbar and Jahangir, the ateliers remained functional during the reigns of Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb. While Shah Jahan maintained funding for the atelier, his interest was mainly directed towards architecture. The paintings of this period were formal and lacked the flair for experimentation or aesthetic interest under the previous emperors, as the Mughal court viewed painting at the time as a medium of courtly representation. However, the muraqqas and illustrations in texts like the Padshahnama were highly naturalistic and technically accomplished. Aurangzeb’s religious orthodoxy led him to direct funding away from the atelier a few years into his reign, but for most of the 1660s the emperor tolerated painting as a courtly art. Several highly valued examples of portraits and durbar scenes in the Mughal style were produced in this period. With the exception of a revival under the reign of Muhammad Shah (1719–48), patronage for miniature painting had dwindled enough in the eighteenth century that artists were forced to seek employment outside the imperial court, thus lending a strong Mughal element to the painting traditions of smaller kingdoms, particularly Rajput and Maratha courts. With the advent of British rule, the tradition of Mughal miniature painting, with its emphasis on naturalism, was incorporated into the Company school. Today, dispersed folios and, more rarely, whole manuscripts in the Mughal style, are housed at various museums across the world.

ARTICLE

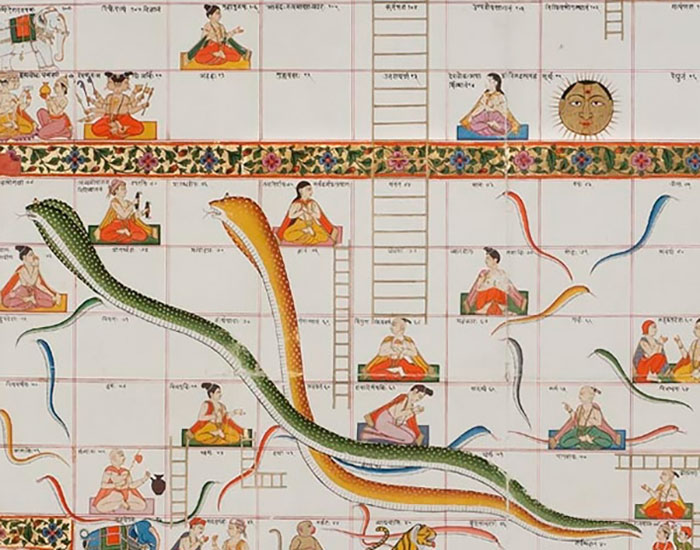

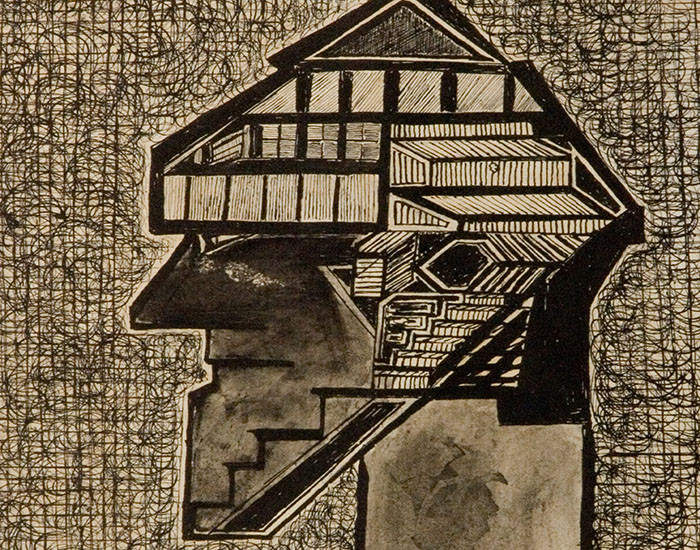

Also called miniature paintings due to their intricacy and small scale, manuscript paintings are the illustrations of key scenes that accompany the text in a range of historical Indian books, including romances, epics, works of fantasy, travel literature, religious texts and biographies. In this sense, illustrated manuscripts are distinct from muraqqas, which were albums of individual painted images made for a patron’s personal perusal. The tradition of illustrating manuscripts in the Indian subcontinent dates back to the ninth century, or possibly earlier. Historically, most manuscripts were made on commission from wealthy patrons, as a result of which manuscript painting became a major court art during the medieval period in India. In many cases, manuscripts were also used for storytelling performances at these courts, with the image on the front-facing side and the corresponding text on the reverse side of a folio, allowing the performer to check the text as they displayed the illustration to the audience. The systems of producing these manuscripts would vary: in some cases, a single artisan illustrated an entire book, but manuscript painting was typically done by an atelier of at least a few artisans, working under a master painter. Well-established artisans were retained for long periods by particularly wealthy courts with rulers who had a keen interest in the arts, but for the most part artisans worked with clients on a project basis. Teams of artisans divided the work among themselves on the basis of specialisations such as portraiture, patterning, painting costumes and accessories, or the rendering of animals, birds and plants. While Indian traditions of manuscript painting vary greatly in style, they are typically rendered in a flattened perspective and a variety of colours, with patterned borders featuring floral or geometric motifs. Wherever patterns are included in the painting – such as on a figure’s clothes, upholstery or architecture – these are reproduced evenly as though on a flat surface and rendered with great care to maintain uniformity. Manuscript painting traditions that were directly or indirectly influenced by the Persian style typically have a lighter colour palette, a high horizon line and tend towards naturalism in the rendering of faces, flora and fauna. The intricacy of border patterns, neatness of composition and use of expensive colours such as gold and ultramarine blue are some common indicators of a manuscript painter’s skill and abilities as well as a patron’s tastes and wealth. The major traditions of manuscript painting in the Indian subcontinent are Pala Buddhist painting in eastern India and Nepal; Jain manuscript painting in western and central India; Mughal and Rajasthani painting in northern and western India respectively; Deccani painting in southern India; and Pahari painting in the kingdoms at the foothills of the Himalayas. In addition to, and often within, these categories smaller kingdoms had their own manuscript painting styles and ateliers, which usually came under the influence of the major schools. Additionally, some notable manuscripts have been found whose makers and patrons remain unknown. Among these are Majuli manuscript painting, Bengal Sultanate manuscript painting, Awadhi manuscript painting, a Jain-style Shahnama, the Nimatnama-i-Nasiruddin-Shahi cookbook, and an illustrated copy of the Chandayana. Apart from imperial patronage, wealthy merchants or noblemen also commissioned manuscripts, although these are more difficult to date and were executed by minor or inexperienced artists. Exceptions to this include the few European patrons who were active in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, though they typically commissioned albums rather than manuscripts. Manuscript painting in India drew influences from outside as well as within the subcontinent. External influences, which are seen primarily in Deccani and Mughal painting, came from the Safavid court in Persia (present day Iran and Iraq), which had a flourishing manuscript painting tradition from the sixteenth century onwards and became a highly influential cultural presence in Asia as well as the Indian subcontinent. Local traditions of manuscript painting are much older, with some scholars tracing it back to the third or fourth century CE, although the earliest surviving folios date back to the twelfth century and the earliest wooden covers for manuscripts date back to the ninth century. These early folios took the form of narrow, painted palm leaves that were punched with holes and tied together to make books. In fact, within India, manuscripts were made exclusively with palm leaves until the fourteenth century, when paper began to be used in Gujarat for Jain manuscripts. A paper manuscript, called a codex to distinguish it from the palm leaf variety, became the most preferred medium by the early sixteenth century due to its variable size and capacity to hold a wider range of pigments. The palm leaf manuscripts ranged from ten to twenty inches in length, while the codices could reach up to two feet. The codices also had more ornate borders around the images and some of the text as well, likely as a result of Persian influence. Expensively painted manuscripts, especially codices, often used rare or precious materials as pigment, including gold and lapis lazuli, and the high standard for intricate work meant that artists used fine squirrel hair brushes, sometimes comprising a single strand. Religious Jain and Buddhist texts were the most common illustrated manuscripts of the mediaeval period before the establishment of Islamic sultanates in India. The wooden covers discovered are speculated to have been made for a now lost Buddhist manuscript from the kingdom of Gilgit in present-day Kashmir. Later Buddhist palm leaf manuscripts that have survived were made at the monastic centres of Nalanda and Kurkihar (present-day Bihar) in the eleventh century, as part of a tradition now referred to as the Pala school. Jain manuscripts, usually religious in nature, continued to be produced well into the sixteenth century in Western and Central India, drawing influences from the emerging painting tradition in Safavid Persia through existing trade links across the Persian Gulf. Jain and Buddhist manuscripts typically gave more importance to the text, with the images playing a largely decorative role. In later traditions, however, both text and image were crafted and patronised to an equal degree. Pluralism has been a major characteristic of manuscript painting in India, with Jain, Hindu and Muslim patrons and artists creating manuscripts with themes that draw from a wide range of religious and cultural material. As a result, there was a rich and rapid exchange of styles in the subcontinent as artists trained in various schools moved from court to court. Beginning with Akbar’s patronage of the art form in the second half of the sixteenth century, Mughal manuscripts became the most influential style in India, attracting painters and calligraphers from across regions and cultural backgrounds, including some from Persia. Mughal painters were also influenced by Western art and adopted some of its attributes, most notably the more naturalistic aerial perspective. At roughly the same time, the Deccan kingdoms that had broken away from the Bahmani Sultanate in the sixteenth century began commissioning illustrated manuscripts of their own, first in a highly original elaborate aesthetic and then in a more noticeably Mughal style. Although some kingdoms in present-day Rajasthan also began patronising manuscript painters around the same time as the Mughal court, the Rajput style emerged in earnest only by the late seventeenth century, as painters left the declining ateliers of the Mughal court. From the early eighteenth century onwards, Pahari painting flourished as a distinct genre in kingdoms established by Rajput kings in present-day Himachal Pradesh. By the late nineteenth century, illustrated manuscript painting was largely replaced by photography and large Western-style portraiture. These art forms appealed to rulers of the Princely States under British rule both in a technological and cultural capacity. While illustrated manuscripts are no longer produced, the most recognisable styles of such painting have been adopted by several contemporary artists from Pakistan, most notably Shazia Sikander, Bashir Ahmad, Saira Wasim and Imran Quereshi. In India, miniature painting has also been a major influence on artists of the Baroda school and Bengali modernists such as Nilima Sheikh and Abanindranath Tagore.

The process of stamping designs fabric using dye-soaked, hand-carved wooden blocks is known as woodblock printing.

The convenience of combining motifs and intricate patterns on different blocks to create unique designs made the resulting textile affordable and appealing. Some of the more popular block printing traditions include ajrakh, bagh, bagru, sanganeri, saudagiri, mata ni pachedi, namavali and balotra, as well as the less popular traditions of the Chhimba community in Punjab and the more recent printing practices in Serampore of West Bengal.

Although block printing is believed to have been practised in a rudimentary form as early as the Indus Valley civilisation, the earliest material evidence of these textiles and their international trade came from fragments of cloth from Gujarat, found in Egypt and Indonesia, dated to the thirteenth or fourteenth century. The Indian Ocean trade in Indian textiles continued until it was taken over by the British East India Company and the Crown in the nineteenth century.

While several Indian communities practise the craft, the Khatris and Chippas in the country’s northwestern regions are the oldest known communities to have been continuously involved in block printing, going back as far as the sixteenth century.

ARTICLE

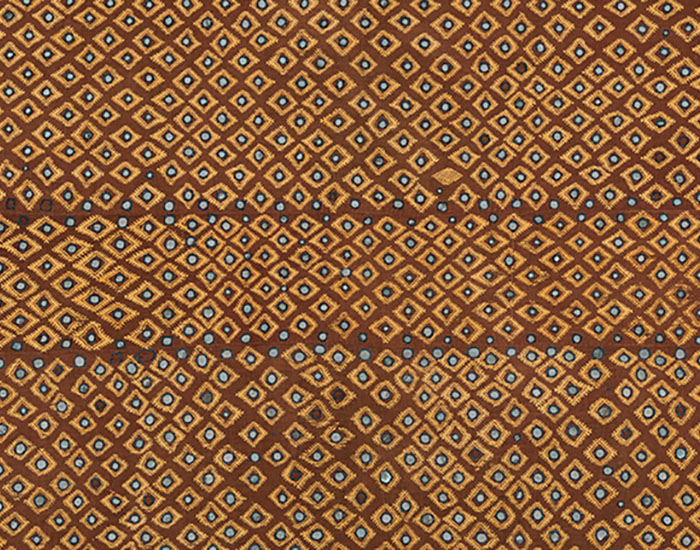

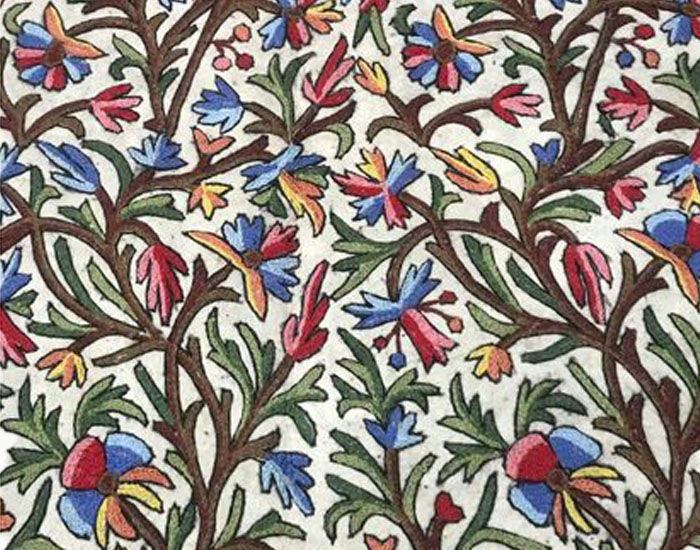

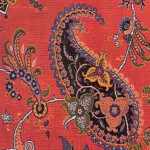

The process of stamping designs and patterns on base fabrics such as cotton or silk using dye-soaked, hand-carved wooden blocks. The technique is central to a variety of printing traditions across India in which blocks are used to create a range of designs composed of floral and religious motifs, geometric forms, and calligraphy. Some of these block printing traditions include ajrakh, Bagh, Bagru, Sanganeri, saudagiri, mata ni pachedi, namavali, and balotra, as well as the less popular traditions of the Chhimba community in Punjab and the more recent printing practices in Serampore of West Bengal. While several Indian communities practise the craft, the Khatris and Chippas in the country’s northwestern regions are the oldest known communities to have been continuously involved in block printing, since at least the sixteenth century. Although, block printing is believed to have been practised in a rudimentary form as early as the Indus Valley civilization between 3000 BCE and 1200 BCE, direct textual evidence dates the craft of block printing on textiles to the eleventh century in Kerala. The earliest material evidence of these textiles and their international trade came from fragments of cloth from Gujarat found in Egypt and Indonesia dating back to a period between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. It has been inferred that these textiles were printed and dyed in blue and red during that time — and some were hand-painted using the technique of kalamkari. Block-printed fabrics had experienced sustained international trade in the western and eastern regions of the Indian Ocean, before the establishment of first Europe-mediated and then European trade between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries. The initially indirect trade was routed through the existing Indian Ocean and Southeast Asian markets by commercial officers from Portugal and the Dutch East India Company and French East India Company. The cultivation of a robust European market for Indian printed cloth such as Kalamkari and chintz, proved lucrative by British East India Company, which began to establish trade monopolies from the seventeenth century on. The visual appearance of any block printed textile depends on the quality of the carving on the block, the richness of the dye and the effectiveness of the mordant used with it. While engraved blocks of metal and terracotta are sometimes used, those made from types of wood such as sheesham, sagwan and rohida are often preferred for their texture and ease of carving. Woodblock carving has been traditionally carried out in Gujarat and Rajasthan, each with producing blocks in distinctive styles. While in Gujarat, Pethapur has been the centre of block making, in Rajasthan, it is Jaipur that serves as the primary centre, both serving printing and dyeing clusters in their respective states as well as in Madhya Pradesh. is the primary blocks from Jaipur are best known for their precise cuts, which allow for cleaner printing with a lower risk of smudging. Contemporary block makers still prefer to use hand tools such as chisels to carve the blocks, alongside some mechanised tools such as small drills. Teak is the preferred variety of wood for making blocks, as it remains undamaged even after frequent contact with water and other substances used in the printing process. Air passages known as pavansar are also often drilled into the blocks to prevent them from clinging to the fabric when lifted. A single printed motif may require the use of multiple blocks. For instance, one block can be used to create a rekh of the motif, another can be used to fill it, such as a datta, and a third block, such as gadh, can be used to create the background of the design. This requires both the block maker and printer to be aware of how every block will be used, and how the motifs will fit into the design. karigars also mark the date on each block, in case it needs to be repaired or altered, so that patterns will repeat perfectly when the fabric is printed. Prior to printing, a mordant is typically added to the dye to allow it to stick to the base fabric because many natural dyes do not easily adhere to the cloth. Only a few — such as indigo, which is used in several block printing traditions and was a key product in colonial extraction — do not require the use of mordants. Although natural dyeing and printing was a thriving practice in India until the nineteenth century, karigars eventually began relying almost entirely on inexpensive chemical dyes. The use of such dyes has allowed two types of manual printing techniques to emerge: direct printing and discharge printing. In addition to block printing, karigars also sometimes employ resist-dyeing, which includes techniques such as dabu printing and batik. Block printing, indigo dyeing and resist dyeing are often combined to produce complex, layered and multi-coloured patterns in traditions such as the aforementioned ajrakh, Bagru and Bagh. The block printing technique in each region of the country is distinct, localised in terms of the materials and tools used as well as the cultural influences and social characteristics of particular communities. Traditionally, the raw fabric, motifs, colours and intricacy of block printed garments have served as designators of the wearer’s identity, caste, community, status and occupation. However, with the onset of urbanisation and market-driven mass production, these textiles have been redefined and adapted for contemporary consumption and usage, losing much of their social and symbolic values. Block printing has had a long tradition in Asia, and particularly India, which though having undergone much change to meet varying market demands and technological and lifestyle changes, has mostly remained authentic and uncompromising in aesthetic and technique. Block printed fabrics have in recent years experienced an upsurge in Indian and international markets, leading to more concerted efforts towards the conservation and revitalisation of indigenous block printing traditions. One f the largest repositories of Examples of printed textiles and garments have constituted the collections of museums in India — such as Sanskriti Museum of Indian Textiles, Calico Museum, and the Anokhi Museum of Hand Printing.

ARTICLE

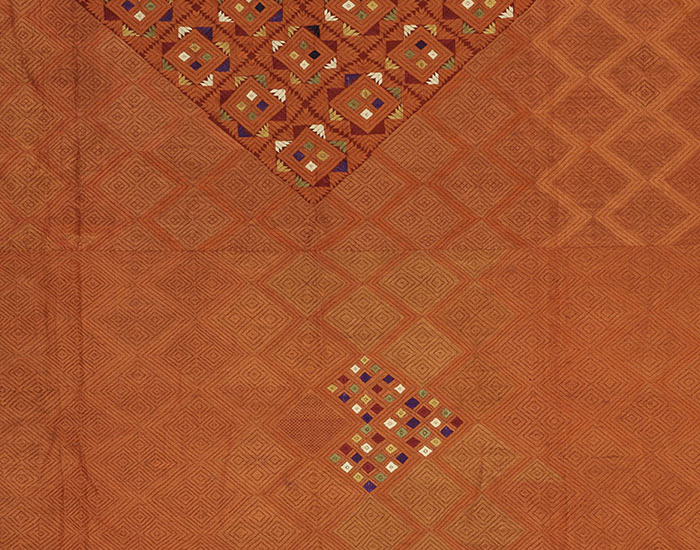

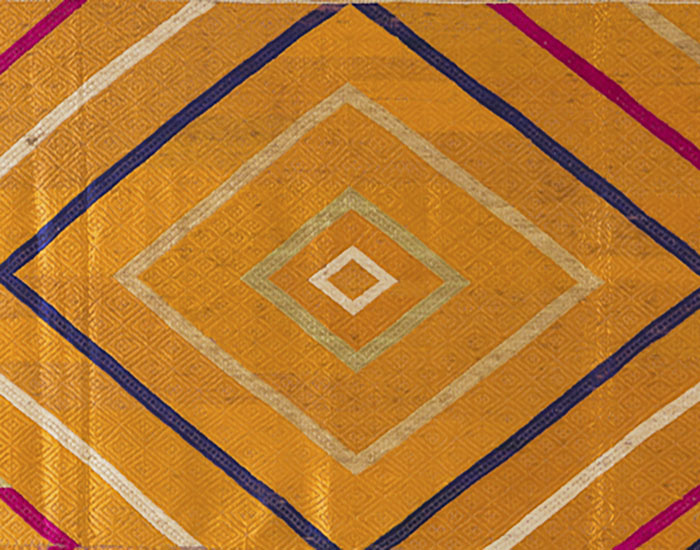

This block printing technique for textiles derives its name Balotra from the city in the Barmer district of Rajasthan where it is primarily produced. Balotra printed fabrics are characterised by their vertically arranged floral and geometric butis that appear in earthy reds and yellows, as well as cream, over a base that is dyed deep indigo or dark green. These butis are usually large and often printed without the use of a black rekh, or “outline,” resulting in bold and simple designs without the nuances of colour evident in textiles such as ajrakh or Bagru. A unique feature of Balotra printing, considered an extension of ajrakh printing, is that it is done on both sides of the cloth and in quick succession. As with block printing traditions in other parts of Rajasthan, such as — Bagru and Sanganer — the karigars in Balotra belong to the Chhipa community. Oral traditions of the community indicate that woodblock printing has been practised there for many years. After the Partition of India, many Muslim Chippa families migrated to Pakistan, leaving a gap subsequently filled by an influx of Hindu Chippas into Balotra. The waters of the seasonal Luni river and Rajasthan’s hot and dry climate made Balotra well suited to the traditional methods of dyeing and printing that the immigrant and native Chhipas and Khatris had been practising. The preparation and printing of the fabric are similar to that of Bagru, although it is not as laborious or repetitive. The fabric, usually cotton, is first washed and beaten to remove impurities and soften its fibres, and then soaked in water for anywhere between twelve and seventy-two hours. In a process known as saaj, the fabric is treated using a mixture of castor oil, camel or goat dung, and soda ash. While still wet it is soaked in a paste of harda, which lends the cloth a yellow tinge and allows it to develop deeper blacks. Once dry, the designs are transferred to the fabric with wooden blocks in multiple stages: first using direct printing — in which dye is applied to the blocks and pressed onto the fabric — and then using dabu (or dye-resist) printing. The latter of these two processes is more complex as it serves additionally to protect the base colours of the prints from the eventual dye baths. The dabu paste is first made by combining clay, beden, lime and natural gum and fermented for several days. This mixture is then printed onto cloth using wooden blocks, after which it is usually sprinkled with beden to keep up from smudging and to help it dry quickly. Once dry, the fabric is soaked in vats of dye and then thoroughly washed to remove traces of the dabu paste. When dried again, the fabric reveals the dabu printed parts as undyed. A single fabric may be subjected to multiple rounds of dabu printing and dyeing, depending on what the design demands. Direct printing is used for colours such as black, made from a mixture of iron filings, jaggery and natural gum; red, made from natural gum and alum; and grey, khaki and brown, from kashish. Other colours in the palette include indigo-blue, green and a marigold yellow — all created using natural dyes. Balotra print fabric was traditionally used for the attire of women — ghagra (skirt), choli and odhani (a draped cloth) — from various regional communities. Dark-coloured fabrics that mask traces of dirt were used every day as they were better suited to labour, whereas the relatively uncommon lighter variations were reserved for special occasions. The printed cloth also served as social designators, with colours, motifs and patterns being used as differentiators of ethnicity, religion, socio-economic position, occupation and marital status. For example, the phooli, gainda and chameli are motifs worn exclusively by the Mali community. Others such as Rabari ro fatiya and Maliya ro fatiya, named after their respective communities, and the tokriya for the Rabari and gul buta for the Jain communities are all worn by widows. The mato ro fatiya is worn by women who are pre-construction workers, the trifuli is worn by young betrothed girls in Marwar. Motifs derived from names of medicinal and talismanic plants, such as laung and nimboli are worn by married women and by Chaudhary women and Mali widows, respectively. Other motifs such as methi, worn by widows from several communities, and goonda, worn by married Chaudhary women, are based on locally available plants commonly used in cooking. Since the 1990s, traditional Balotra printing has seen a steady decline as local printers have turned to other professions and as the appeal of less-expensive chemical dyes, polyester fabric and screen-printing methods have simultaneously increased. Only a handful of Chippa karigars who use traditional methods to produce authentic Balotra prints remain. These artisans work to supply local communities while also expanding their customer base by adapting traditional designs to decorate household textiles such as floor coverings, bedsheets, pillows and cushion covers.

ARTICLE

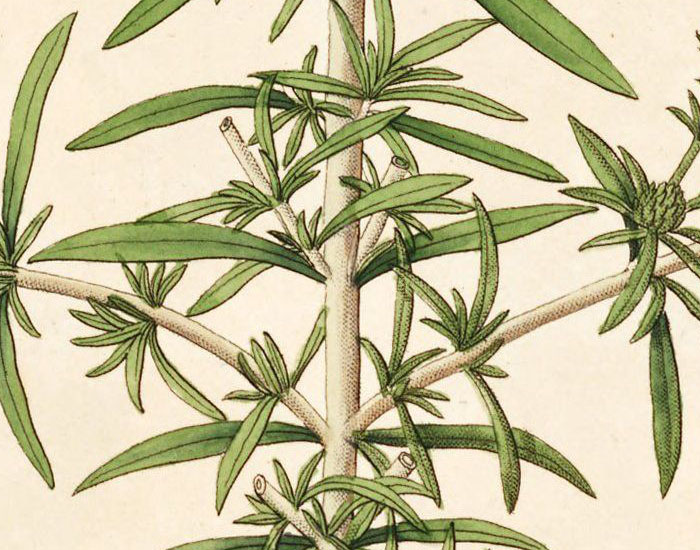

A traditional form of block printing locally known as thappa chhapai using natural dyes, Bagh has historically been practised by Khatris in a town of the same name in the Dhar district of Madhya Pradesh. These prints are characterised by a combination of their colour palette of black, red and white, and their intricate naturalistic and geometric motifs. Other features that distinguish the Bagh printing process from ajrakh, also practised exclusively by the Khatri community, is that the colours desired in the final product are applied directly on the undyed base fabric — instead of through a resist-dyeing process — and that the cloth is printing only on one side. Members of the Khatri community migrated from Sind (now Pakistan) nearly five centuries ago and settled in parts of Gujarat, Rajasthan and eventually Madhya Pradesh. They chose Bagh due to its location on the banks of the copper-rich Baghini river and its proximity to markets. Over time, the Khatris evolved a printing and dyeing technique that utilised local resources and catered to the Adivasi (Bheel and Bheela) and Rajput communities. The distinctive Bagh tradition emerged with the development of improved black and red colours (using iron rust and alum) as well as vegetable dyes and the incorporation of regional influences and visual motifs. The motifs and designs of Bagh prints, also known as alizarin prints, are produced by wooden blocks carved in Pethapur, Gujarat. The repertoire of traditional designs and motifs include chameli , maithir, kairi and jurvaria, which are then set in nariyal, leheriya, tikona and gehwar patterns. Some patterns, such as the jaali, or “trellis,” are said to have been inspired by monuments such as the Taj Mahal. The process of making Bagh prints is laborious and demands great attention to detail. In preparation for printing, the fabric is soaked in water overnight, dried and then dipped in a mixture of goat droppings, sanchiri, castor oil and water. It is then dried, washed, dried again and laid atop low tables in front of a karigar seated on the floor. The karigar’s work begins with printing the outline, followed by filling it in with colours and details. The red and black designs are printed in separate stages, allowing the natural dye to dry before the next layer of the design or colouring is applied. Red dyes are made from Aal (Morinda citrifolia), with alum functioning as a mordant, while black dyes are made by combining iron filings and jaggery. A paste made of tamarind seeds is typically used as a binding agent. Once dried for ten days, the fabric is taken to the river, where it is washed and beaten against rocks to soften it and remove excess dye — a process known as vichaliya — after which it is laid out to dry on the banks. The dye is then fixed and the reds are deepened by boiling the cloth for a couple of hours in a solution of alizarin and local dhawda flowers. In a final step, the fabric is washed once again in large tanks known as haudis and then laid out to dry. Threatened to the point of extinction by the advent of synthetics and rapidly changing lifestyles, Bagh printing was kept alive and subsequently contemporised by the efforts of a few prominent Khatri families. An award-winning duo, the late Ismail Suleiman Khatri, and his wife Hajjani Jetun Bi, are master karigars who have been credited with keeping the printing tradition alive in Bagh. Their five sons are all acclaimed karigars who continue to practise and popularise the craft, adapting their designs to suit contemporary aesthetic sensibilities. Among them, Mohammed Yusuf Khatri is prominent for his role in preserving the craft and improving the local economy by training the local non-Khatri artisans in Bagh block-carving and printing, and by expanding the design repertoire and introducing them to a larger market in the form of sarees, stoles and home linen. The next generation of Khatris have carried on this work, extending training and experimenting with materials such as reed mats to ensure the relevance and sustainability of this block-printing tradition. In 2008, Bagh prints from Madhya Pradesh received Geographical Indication (GI) status from the Government of India for their territory-specific production and characteristics.

ARTICLE

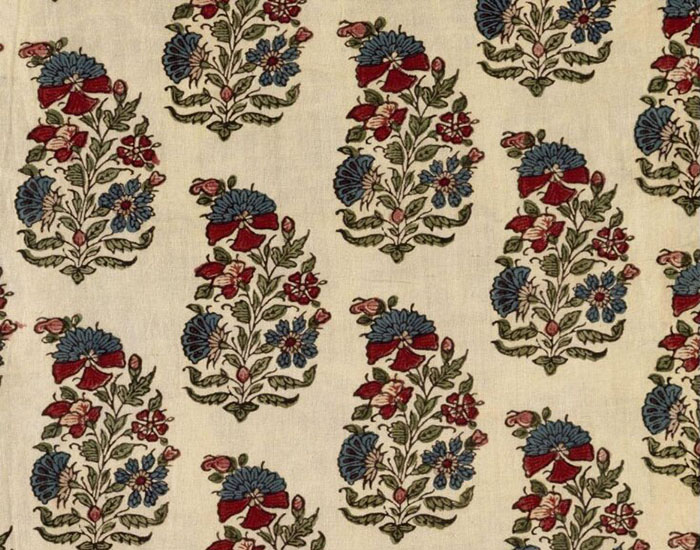

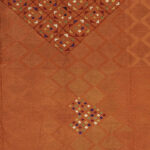

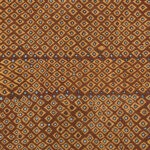

A textile block printing technique that features repeated floral buti arranged in various patterns. Commonly seen butas in Bagru prints include gainda, gulab, badaam, kamal and bel. These motifs appear in varying sizes and combinations throughout the cloth on which they are printed. Other designs feature smaller jaali patterns, also composed of floral motifs. Bagru prints employ natural dyes, most frequently black, derived from a mixture of iron filings and jaggery and gum; red, from a mixture of madder and alum; and grey, khaki and brown, derived from kashish. Other colours in the palette include indigo, green and yellow. Named after the city in Rajasthan where it originated, the technique is primarily practised by the Chippa community in Bagru, Rajasthan. The city’s proximity to the Sanjariya river was ideal for the repeated washes required by the technique. Bagru’s clay-rich soil is also an essential element in the printing process, and the area’s warm climate allows fabrics to dry easily. Bagru printing involves multiple stages of washing, drying, printing and dyeing. The fabric, usually cotton, is first washed and beaten to remove impurities and soften the fibres, then soaked in water for twelve to seventy-two hours. The fabric is then treated using a mixture of castor oil, camel or goat dung and soda ash in a process known as saaj. The still-wet fabric is then soaked in a paste of harda, which lends the cloth a yellow tinge. The harda allows the fabric to develop deeper blacks. The fabric is then dried, after which the designs are transferred to the fabric using wooden blocks in multiple stages: first using direct printing — in which dye is applied to the blocks and pressed onto the fabric — then using dabu printing. A single fabric may be subjected to multiple rounds of dabu and dyeing according to the demands of the design. As with other block printing traditions such as Bagh and ajrakh, karigars print the outline before progressing to the filler colours and other finer details of the designs. Usually, a set of three hand-carved blocks are used to create each floral motif — a rekh block, a background colour block called gadh and a colour-detailing block called datta. The blocks are carved out of sheesham wood, with the process of carving and seasoning each block set taking about a week. In the past, chippas were printed on coarse, hardy reja cotton for local peasant and pastoral communities for garments such as ghagras, odhnis, sarees and pagdis. Bagru prints were also used for household products such as angocha, bedspreads, cushion covers and razai. Differing stylisations and combinations of the motifs and colours were developed for each community that wore the prints, allowing traders, farmers and artisans to be identified on the basis of the patterns on their clothes. The original patrons of Bagru prints included Rajputs as well as local communities. Over the last few centuries, the prints have been produced for local consumption, while other floral printed fabrics, such as chintz, have been heavily traded and appropriated in the West. Today, there are about fifty to sixty blockprinting workshops in Bagru, with a community of over five thousand workers. Both women and men participate in the printing process. To cater to contemporary markets, printers use fine fabrics that aren’t limited to cotton. While most of these workshops produce woodblock-printed cloth, some have now employed the screen-printing method, which is less laborious. Many karigars also use chemical dyes.

ARTICLE

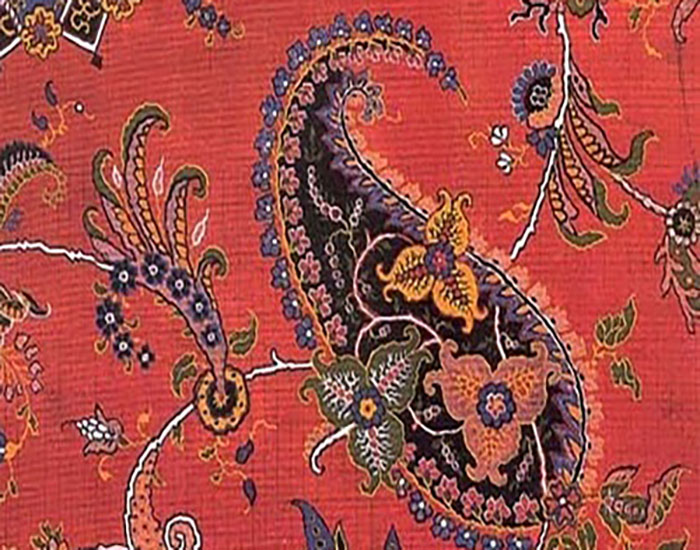

A textile block printing technique created by resist dyeing. The term also refers to the resulting fabric, usually cotton, which features floral and geometric motifs printed in darker colours such as indigo and red. While the etymology of the word ajrakh is contested, the Arabic origin of the word — from azraq, meaning “blue” or “indigo” — is the most commonly accepted. It is also believed to derive from the Hindi aaj rakh, meaning “keep for today”. Ajrakh production can be traced back to the Indus Valley civilisation, between 2500-1500 BCE. The bust of the Priest King of Mohenjo Daro depicts him wrapped in a shawl with trefoil motifs, similar to the kakar or cloud motif seen in ajrakh prints. Numerous textile fragments dating from the twelfth to fourteenth centuries CE have been discovered at Al Fustat in Cairo, Egypt, and are considered to be the earliest known examples of printed textiles. The fragments, printed with small blocks and dyed using indigo and madder, bear a striking resemblance to ajrakh. The technique has been practised by members of the Khatri community, who migrated from Sindh in Pakistan to Kutch in Gujarat and Marwar in Rajasthan in the sixteenth century, settling in places that had access to flowing water, which is essential to the ajrakh process. Several karigars (craftspeople) relocated to Ajrakhpur in Gujarat following the 2001 earthquake. The process of creating ajrakh textiles has evolved significantly, from resist-patterning on one side of the cloth to two-sided resist-printed cloth. The printing blocks are often carved in pairs, thus registering an exact inverted image on the other side of the cloth. The production process for ajrakh is notably laborious. The fabric is first washed, beaten and rinsed to soften it and remove impurities. In a process known as saaj, the fabric is treated with a mixture of castor oil, camel or goat dung and soda ash. It is then dried and smoothened to ensure accuracy in the printing process. In the subsequent step, called kasanu, the fabric is dyed using harda, which lends it a yellow tinge. After it dries, the fabric is laid on low printing tables, where a karigar prints a rekh using a mixture of lime and natural gum, which acts as a resist. If the cloth is to be printed on both sides, the rekh is applied on the reverse side as well. The lines printed are resistant to alizarin as well as indigo, showing up as white in the finished product. In the next step, kut, a dye made of iron, jaggery, assorted millets and tamarind, is used to print another set of lines within and over the initial rekh. These lines oxidise when exposed to air and the harda and develop a black colour. Next, a dye that uses alum as a mordant is used to fill in the red details. A paste called pa, made using clay, millet flour and dhawda gum, is applied over these filled-in details to make them resistant to indigo dyeing. Dry cow dung powder is then sprinkled over the wet pa to prevent the resist from spreading. Once the printed lines have dried, the cloth is ready for dyeing. It is dipped in large vats containing a mixture of indigo, lime, jaggery and mustard seeds. The dyed cloth emerges a bright green that slowly turns blue once the dye oxidises. Various natural dyes may be added to the fabric before this stage. The cloth is then repeatedly washed and dried. Following this, the fabric is dyed red by soaking it in a solution of alizarin, natural gum, dhawda flowers and madder, and stirred continuously. It is then dried and washed, and the resultant cloth is considered a simple ajrakh. It is possible to carry out multiple rounds of resist printing and indigo dyeing to give the fabric added detail and dimension. This more intricate form of ajrakh is known as minakari, named after the detailed enamel jewellery tradition. The blocks used in ajrakh are often carved out of sheesham, rohida or sagwan wood, with cosmic and naturalistic motifs. Some blocks are carved in pairs, allowing traditional master karigars (meaning “artisans” in Hindi) to print fabrics identically on both sides with extreme precision. Traditionally, the Khatris have carved the blocks themselves, although this is now in decline, with blocks being carved in Ahmedabad or Farrukhabad in Gujarat. Ajrakh fabrics were primarily worn only by pastoralist men of Gujarat, Rajasthan and the Sindh regions, typically as a lungi, fainta or gamcha. However, its use is not restricted to special occasions, but functions as a versatile fabric for everyday needs: it is often wrapped as a turban or shawl, and is used to create women’s garments including odhnis and skirts or used as a bedsheet or tablecloth. After extensive use, the fabric softens and can be used to swathe babies, make hammocks and used as patchwork to create quilts called rillis. Today, commercially produced, cheaper versions of ajrakh are screen-printed in parts of Rajasthan. One of the current most prominent master karigars of the technique is Dr. Ismail Mohammad Khatri, who — along with his sons, grandsons and the larger Khatri community — continues to print the fabric in the traditional manner, using only natural dyes.

ARTICLE

A form of kalamkari from southern India, where designs are printed, instead of being drawn using a kalam (pen) are known as Machilipatnam block prints. These prints are presently limited to the town of Pedana, near Machilipatnam, Andhra Pradesh. As a trade textile it was known by several names: chintz by the English, sitz by the Dutch and pintado by the Portuguese. Locally, it is also known as addakam (dyeing) and Pedana kalamkari. The blocks are traditionally carved out of teakwood. The dyes are procured from minerals, leaves, flowers and barks of local trees. The colour red, a distinct presence in kalamkari, is made from a solution of alum and tamarind seed powder; the colour black comes from iron ore; violet is derived from indigo; and shades of yellow, such as mustard and lemon, are derived from varying mixes of turmeric and harad (myrobalan). The fabric is soaked in water for three days to remove starch from it. It is treated with buffalo’s milk and harad, then rinsed and dried for the first stage of printing. The edges of the carved block are pressed onto the cloth, beginning first with outlines and then filling in colour. If the design is supposed to be polychromatic, the red and black portions are printed first, after which the fabric is rinsed and dried to be prepared for a second round of printing. Once printing is finished, the fabric is boiled in a bath with dyes, creating varying combinations of colour. The fabric is rinsed and dried and after another stage of printing with natural dyes the cycle of rinsing and drying is repeated. In the Machilipatnam style, the outline drawing is carved on wooden blocks which are then used to print on fabrics. Unlike handpainted kalamkari, which was a smaller setup concentrated as an inter-generational craft, Machilipatnam print production is carried out in karkhanas (commercial workshops) where block making, washing and printing takes place simultaneously. Srikalahasti, the major centre where kalamkari developed, provided patronage to it through religious functions. Machilipatnam, on the other hand, was an important port city from the medieval period and a bustling trade centre. Due to the textile trade and varying influences of Persian, Arab and European traders, the motifs and designs of Machilipatnam block printed fabric were cross-cultural. Textiles were mass-produced in the karkhanas for trade, leading to a prioritisation of decorative function over the narrative function as was done in Srikalahasti kalamkari. Common patterns include geometric formation, floral patterns, twining creepers, animal figures and ornamental arches and niches. During British rule, Machilipatnam block printing was used to produce textiles for garments as well as for furnishing. While locally it was used for prayer mats, tents and canopies, the European market used it for clothing and bedspreads that were known as palampores. Presently, the craft faces difficult competition from techniques of mechanical printing and digital design. One of the few remaining craftspeople, Pitchuka Srinivas has established a small kalamkari museum for the tradition in the town. The production of kalamkari has been extended to markets of home linens, garments as well as souvenirs and it enjoys a great popularity in the west, where it is routinely exported. Pedana kalamkari received a Geographical Indications (GI) tag in 2013.

Indian textile dyes date back four thousand years, with the earliest evidence being madder-dyed cloth fragments from Mohenjo-Daro dating to the second millennium BCE. Trade of dyes may have begun in this same period, based on the traces of indigo found in Egyptian tombs and the later records of trade with the Mediterranean world. Commercial activity around natural dyes reached its height during the medieval and early colonial periods in the form of block-printed and kalamkari cloth before they were largely replaced by European synthetic dyes.

Indian dyes were coveted not only for their vibrancy and their use in inventive textiles but also because of the carefully guarded traditional dyeing processes, which often involved the application of mineral salts or mordants that fixed the colour to the fabric, making the colours uniquely durable. Shades of blue made from indigo, black from haritaki (black myrobalan) and khair (acacia bark), and a range of reds, lilac and burgundy made from manjistha (madder), chay root, aal (Indian mulberry) and lac insects were the longest-lasting dyes, which is why these colours are still visible on fabric thousands of years later. Yellow dyes are made mainly from haldi (turmeric root) and to a lesser extent kusumba (safflower), palash (Parrot tree) flowers and pomegranate rind. However, natural yellow dyes are relatively short-lived compared to blue or red, as are mixed dyes that use a yellow element, such as greens and oranges.

ARTICLE

A deep red natural dye produced from the roots of the aal tree (Morinda citrifolia or Indian mulberry), aal dye is predominantly used by the Panika community of Bastar, Chhattisgarh and Kotpad, Odisha to dye textiles worn by the Panika, Gond, Muria and Maria communities of the region. There is some evidence that the use of aal dye was widespread historically and that it was once exported to the Mediterranean region; textile fragments containing the dye, dating to the first millennium BCE, having been discovered on the shores of the Red Sea. However, textiles using this dye have not been sold on the general market in recent history. The traditional method of preparing the dye begins with gathering the roots of an aal tree that is between three and four years old, since the roots of older trees lose their pigment. The thin roots are selected, dried, ground into powder at a mill and added to a vat of boiling water to prepare the dyebath. Prior to this, the yarns are prepared for dyeing over nearly two weeks by rinsing and repeatedly dipping them in pots of water mixed with castor oil, after which they are covered in liquefied cow dung, wrung and dried. Wood ash sourced from household kitchens is mixed with water and left to settle overnight, after which the water is separated out. The yarns are then dipped in the ash water and wrung multiple times a day until they froth from the process, indicating that they are ready to be dyed. The alumina dissolved in the water from contact with the ash helps the yarn gain a deep, rich red during the dyeing process. Once the yarns are dry, they are added to the boiling dyebath and stirred continuously until the water evaporates, then dried and dyed again for two or three cycles. In cases where a deep brown colour is desired, iron sulphate is mixed into the dyebath on the third cycle. The resultant colour of the yarns is resistant to washing, light and heat. The roots are harvested and sold to the Panika community by the Parja, Gadva and Muria communities. The women of the community begin dyeing cotton yarn from a young age, and the men weave the yarn into their traditional clothing. Yarns dyed in aal dye are used to make headcloths for men and sarees for women. The dye is known to have a cooling effect, providing some relief to wearers who work extensively in the sun. While aal dye continues to be used today, the level of dye production has drastically reduced owing to the commercial availability of synthetic red and brown dyes as well as finished cotton fabric. The Kotpad Weavers Cooperative Society, founded in 1956, lobbies for government aid on behalf of the dyers and weavers and aids in creating a contemporary market for these goods.

ARTICLE