The Vedas Are Composed

1500–1200 BCE

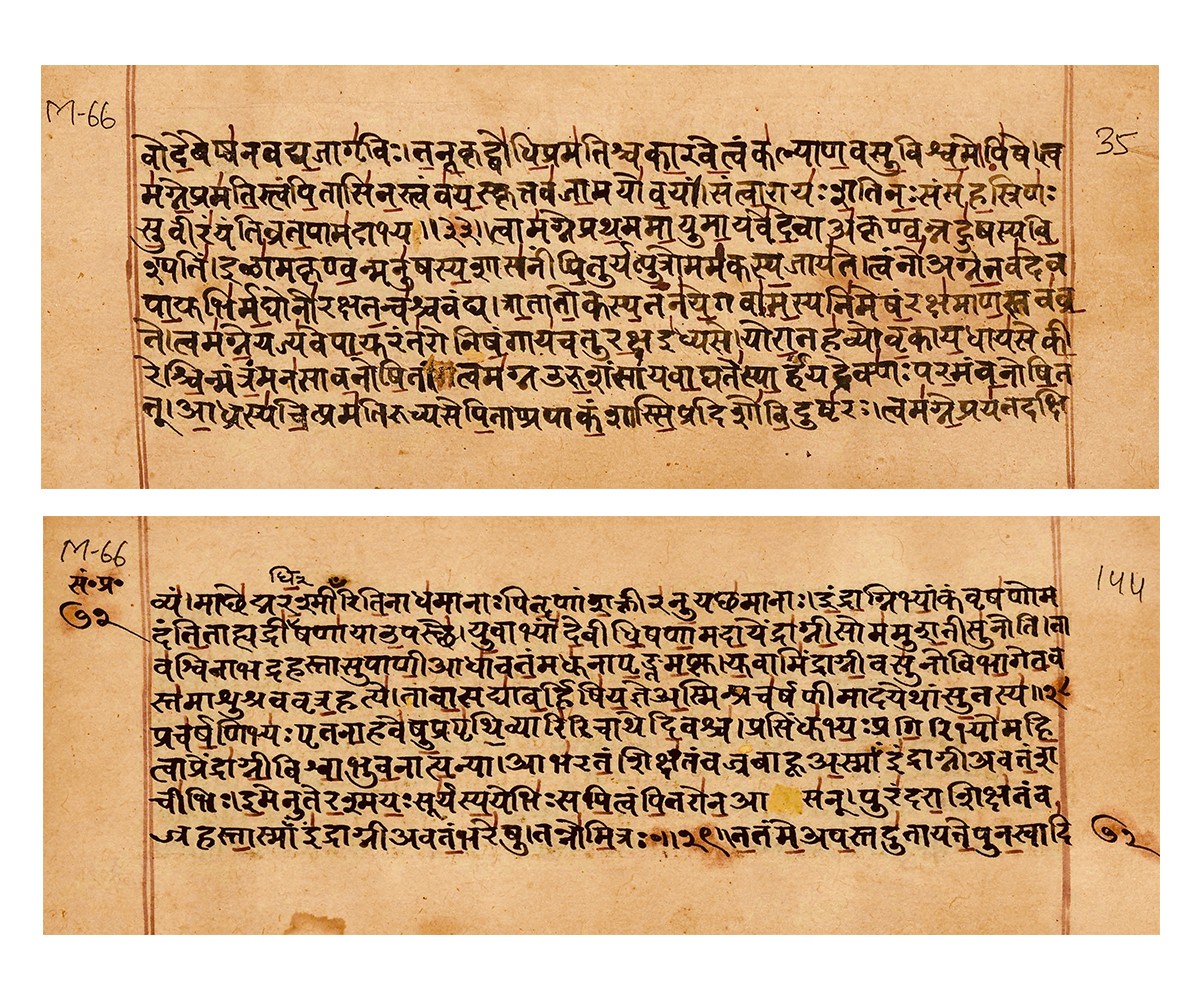

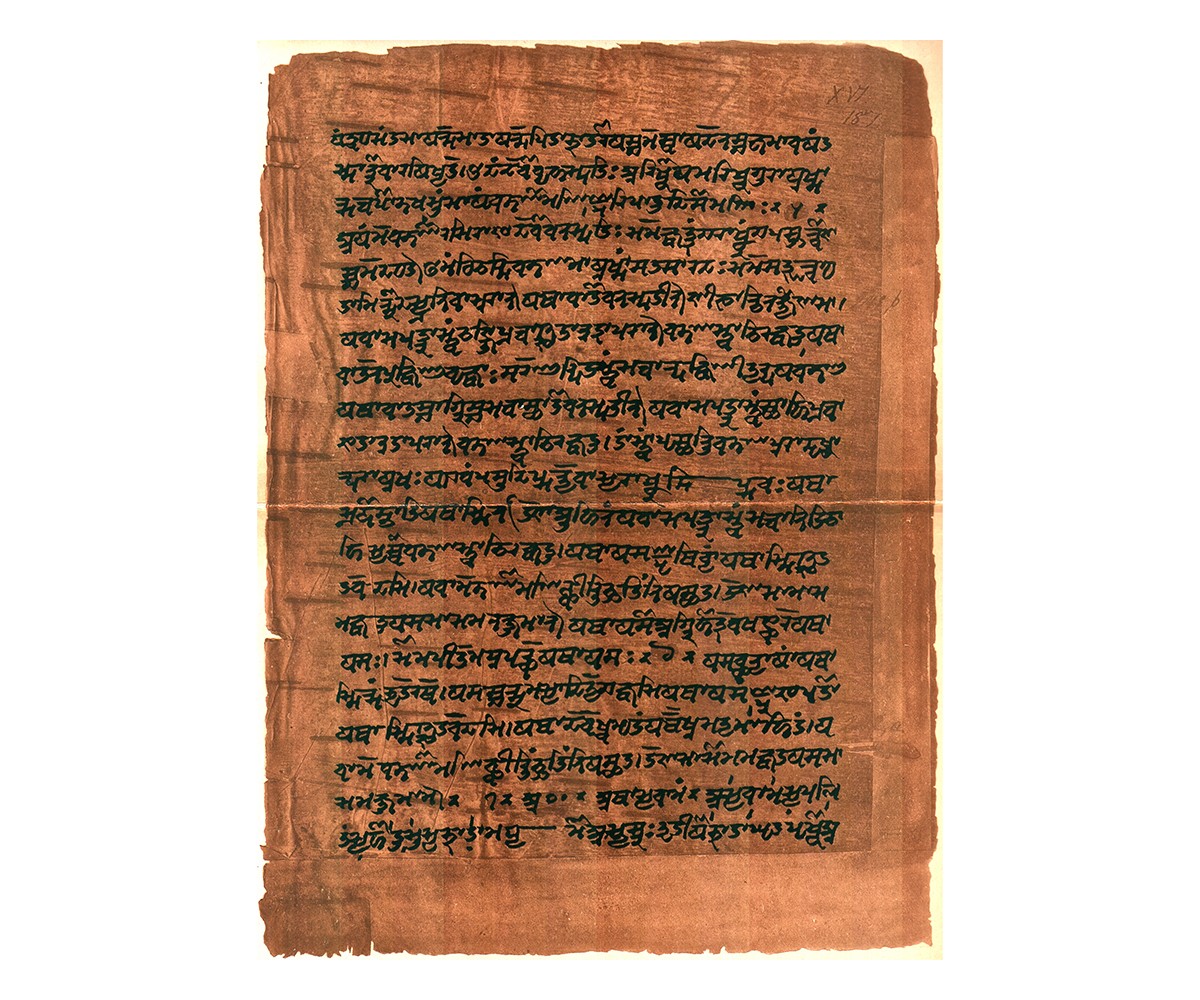

The earliest surviving works of Sanskrit literature, the Vedas (literally ‘knowledge’ in Sanskrit) are composed in present-day northern India and Pakistan. They comprise the Rigveda, Yajurveda, Samaveda and Atharvaveda, each of which is subdivided into Samhitas, Upanishads, Aranyakas, Brahmanas and Upasanas. As the foundational texts of what will come to be known as Hinduism, they are also the oldest known sacred texts in the world. The composition of the Vedas — starting with the Rigveda in c. 1500 BCE — marks the beginning of the Vedic period, when much of the social structure and mainstream cultural hegemony of the subcontinent is established. The short-lived but influential Kuru kingdom is the main site of this new political order and religious tradition.

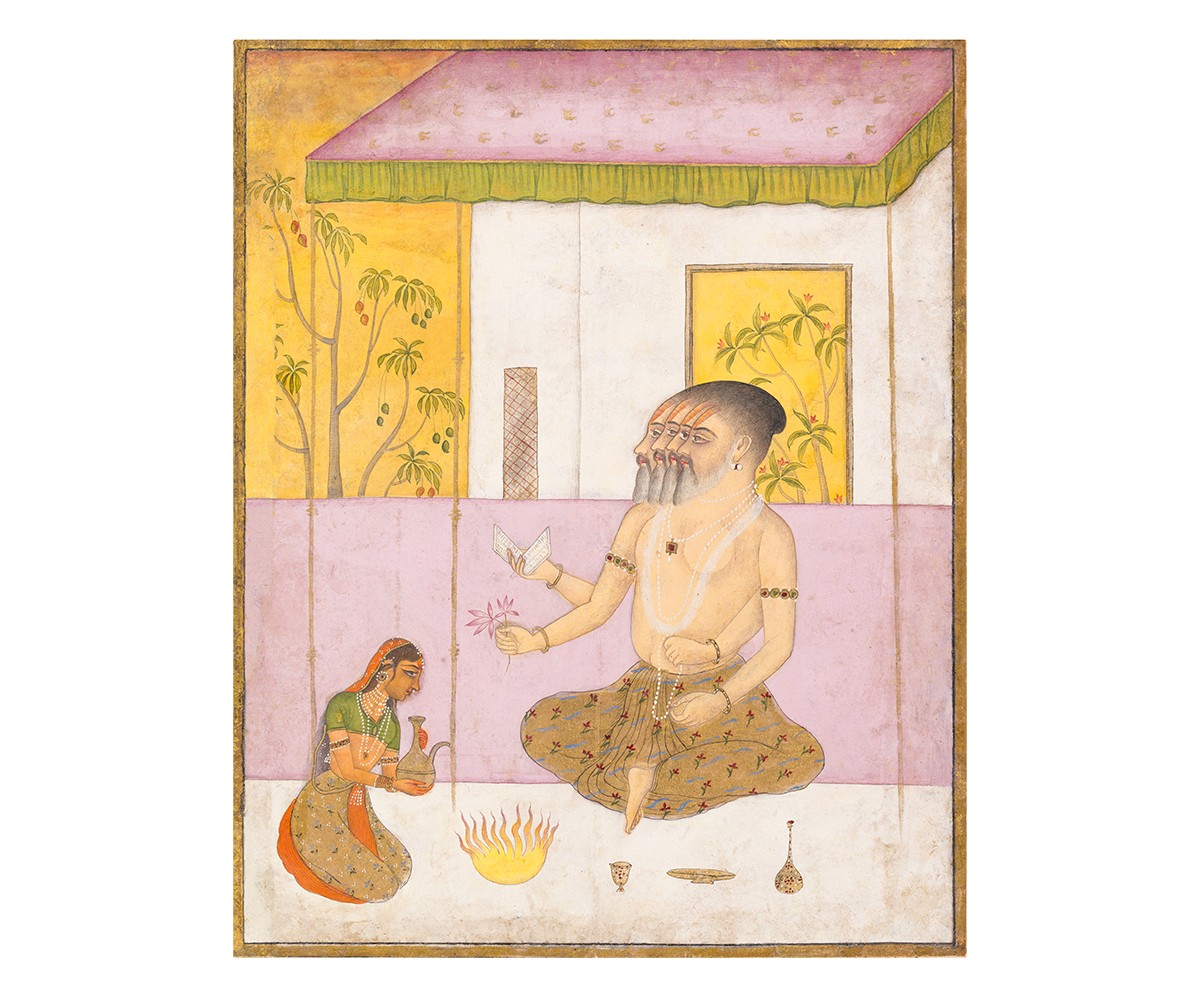

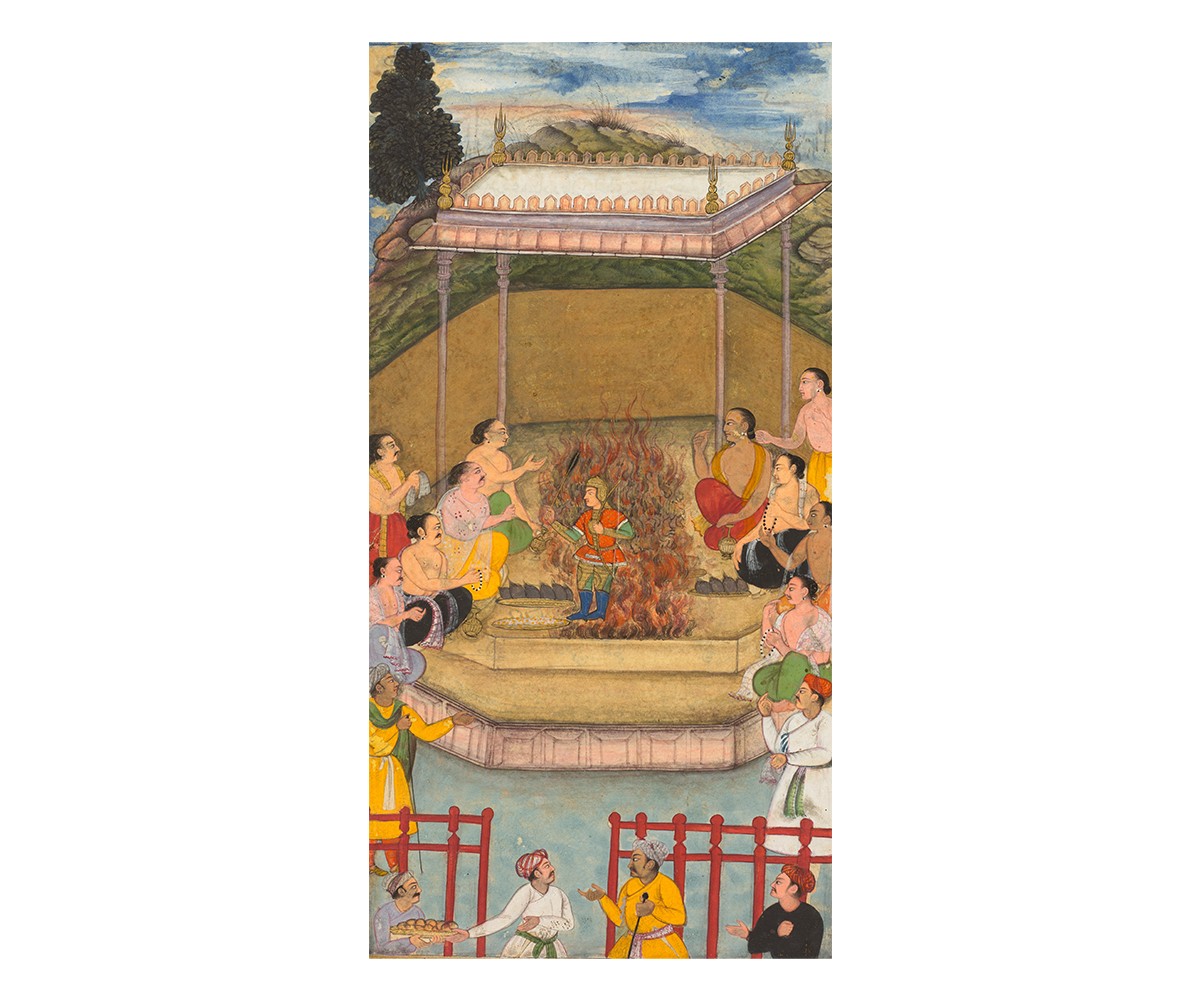

The Vedas are not ascribed to any one author (perhaps intentionally), and are seen as a synthesis of religious, practical and cultural knowledge meant to form the basis of a functional society. Scholars believe they are composed by rishis, or sages, from migrant Indo-Aryan groups who settled in present-day Punjab and Haryana in India after the decline of the Indus Valley Civilisation. The texts describe several key deities and myths in the Hindu pantheon; establish the concept of varna in the caste system; lay out guidelines for rituals and sacrifices; list medical ailments, cures and ideal habits (a body of knowledge that would later be known as Ayurveda); provide the framework for astronomical and astrological charts; outline the structure for a lunisolar calendar, and so forth. The roots of Vedic thought and Sanskrit grammar are echoed (albeit faintly) in regions where other branches of Aryan tribes migrated, as seen in the ritual traditions and languages of contemporaneous Persian and Central Asian societies.

Up to the present day, the Vedas are rigorously memorised and precisely recited as part of the oral tradition of shruti. Scholars have noted that, contrary to popular perception, important texts such as the Vedas have likely undergone relatively little change in their orally transmitted form due to the exacting system of memorisation, in which the texts’ rhythm and cadence are also preserved, not only as a mnemonic aid, but also for their spiritual significance as echoes of the first sounds in the world.

Bibliography

Doniger, Wendy. The Hindus: An Alternative History. New Delhi: Penguin India, 2009.

Dutt, Sagarika. India in a Globalized World. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2006.

Flood, Gavin. An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Holdrege, Barbara A. Veda and Torah: Transcending the Textuality of Scripture. New York: State University of New York Press, 1996.

Inden, Ronald. “Imperial Puranas: Kashmir as Vaisnava Center of the World.” In Querying the Medieval: Texts and the History of Practices in South Asia, edited by Ronald Inden, Jonathan Walters, and Daud Ali, 29–98. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2000..

Mills, Margaret Ann, Peter J. Claus, and Sarah Diamond. South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka. New York: Routledge, 2003.

Singh, Upinder. A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. New Delhi: Pearson, 2016.

Witzel, Michael. “The Development of the Vedic Canon and Its Schools: The Social and Political Milieu.” In Inside the Texts, Beyond the Texts: New Approaches to the Study of the Vedas, edited by Michael Witzel, 258–348. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Mills, Margaret Ann, Peter J. Claus and Sarah Diamond. South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka . Abingdon, UK; New York: Routledge, 2003.

Doniger, Wendy. The Hindus: An Alternative History . New Delhi: Speaking Tiger, 2009.

Dutt, Sagarika. India in a Globalized World . Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2006.

Flood, Gavin. An Introduction to Hinduism . Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Holdrege, Barbara A. Veda and Torah: Transcending the Textuality of Scripture . New York: State University of New York Press, 1996.

Inden, Ronald. “Imperial Puranas: Kashmir as Vaisnava Center of the World.” In Querying the Medieval: Texts and the History of Practices in South Asia , edited by Ronald Inden, Jonathan Walters, Daud Ali (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 29–98.

Singh, Upinder. A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century . New Delhi: Pearson, 2016.

Witzel, Michael. “The Development of the Vedic Canon and its Schools: The Social and Political Milieu.” In Inside the Texts, Beyond the Texts: New Approaches to the Study of the Vedas , edited by Michael Witzel (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997), 258–348.

Feedback

This entry appears in

Art in South Asia

Visit Timeline

Associated Timeline Events

First Published: March 11, 2024

Last Updated: July 2, 2024