Folk Performance Traditions Spread Further

1600–1700

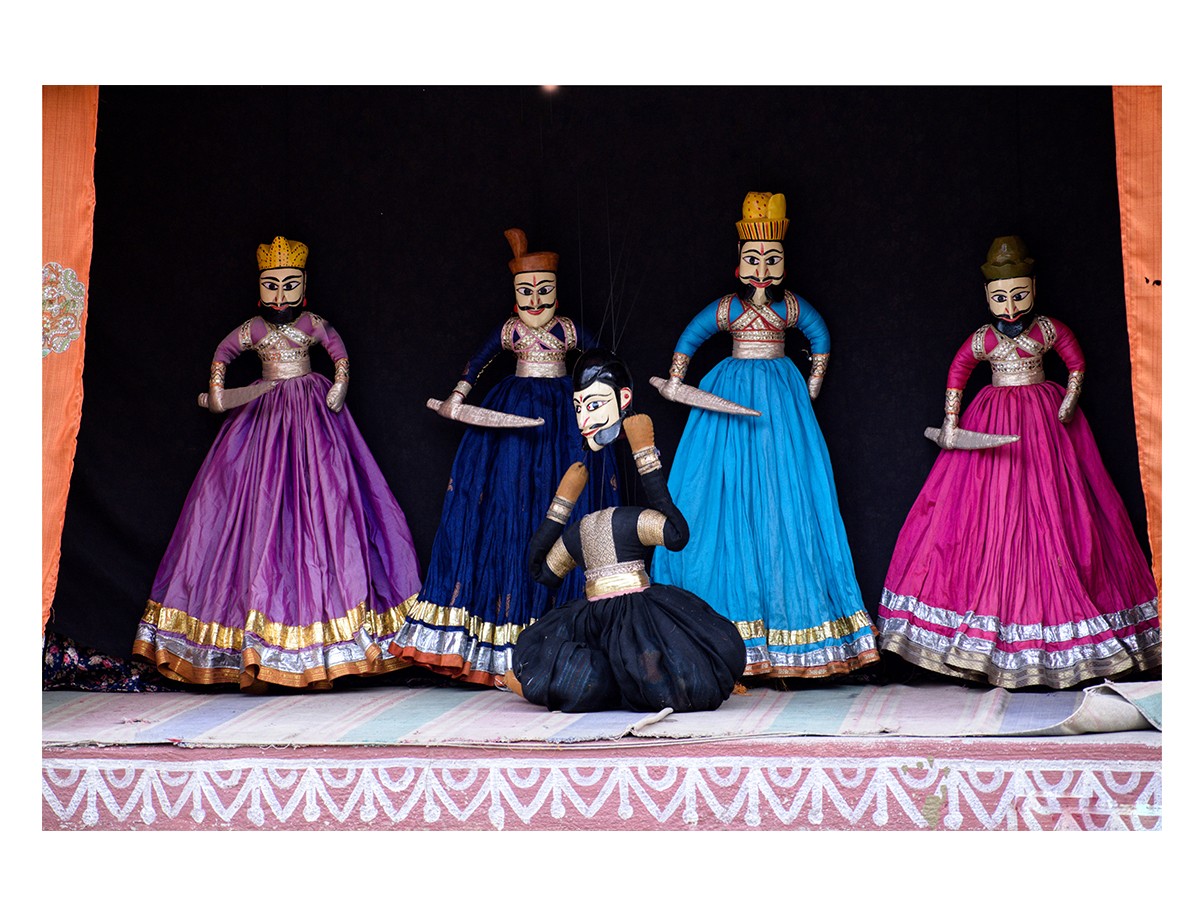

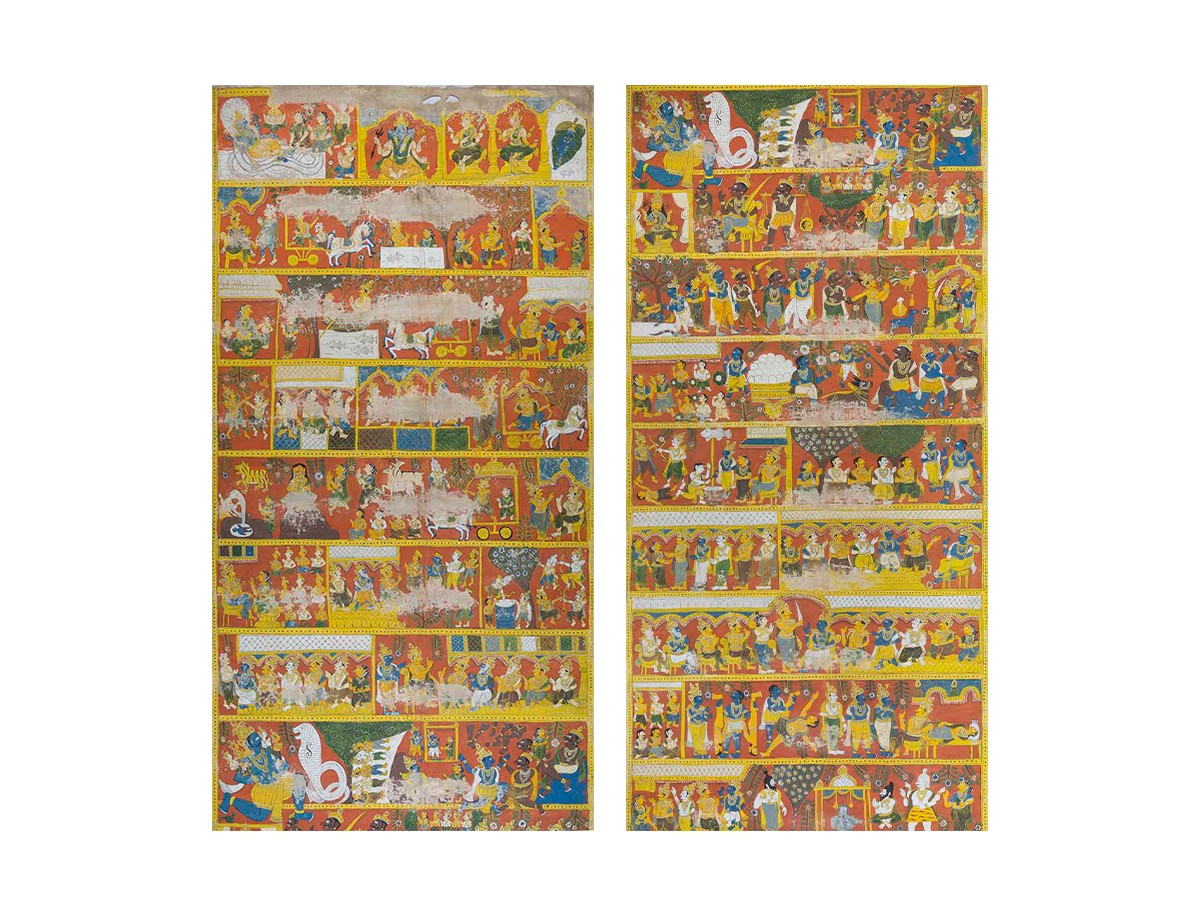

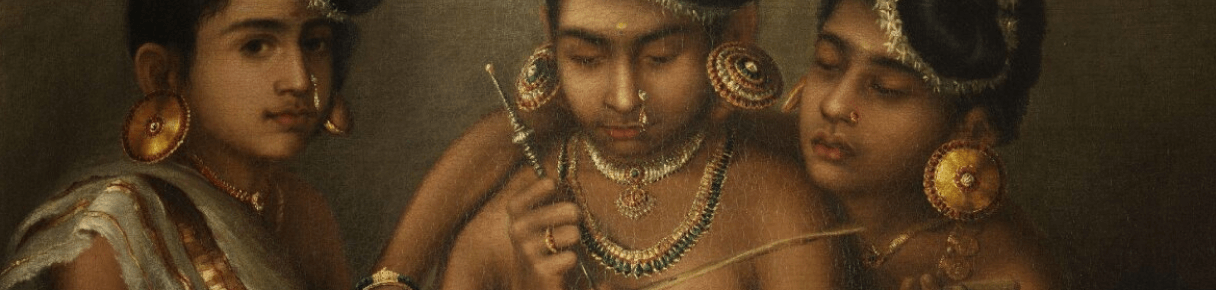

This century sees the emergence of a variety of performance traditions, particularly those practised by nomadic communities. This includes dance and theatre forms like Kathakali and Cham, puppetry traditions like Kalasutri Bahulya and Gulabo-Sitabo, and illustrated storytelling traditions like Cheriyal scroll painting. Art forms that may have existed earlier, most notably Kathputli and Tholpavakoothu, in present-day Rajasthan and Kerala respectively, standardise their narratives and archetypes during this period.

Following different sources of local and royal patronage, artisan communities migrate to the newly established Maratha empire, or within the expanding Mughal empire. Entertainers are welcomed by soldiers and civilian audiences alike, while devotional performers — rarely nomadic — receive steady patronage from local temples and feudal lords.

The movement and spread of influences lead to the development of new traditions in different regions in the same period, which is especially visible in puppetry. In some cases, such as Charma Bahuli Natya, nomadic performers also work as imperial spies, particularly for the Marathas, during the reign of Shivaji.

Bibliography

Awasthi, Suresh. Performance Tradition in India. New Delhi: National Book Trust, 2001.

Chauhan, Sarita. Folk Painting Traditions of India. New Delhi: Institute for Social Democracy, 2012.

Centre for Cultural Resources and Training. Living Traditions: Tribal and Folk Paintings of India. New Delhi: Ministry of Culture, Government of India, 2017.

Stache-Rosen, Valentina. “Story-Telling in Pingulī Paintings.” Artibus Asiae 45, no. 4 (1984): 253–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/3249740.

Feedback

This entry appears in

Art in South Asia

Visit Timeline

Associated Timeline Events

First Published: March 11, 2024

Last Updated: August 5, 2024