The Driglam Namzha and Nationalism in Bhutan

1987–1989

In an effort to emphasise Bhutan’s unique cultural identity, a set of seventeenth-century rules for etiquette, clothing and architecture — the Driglam Namzha — is enforced by the Druk Gyalpo, or the king of Bhutan. This takes the form of multiple royal decrees, including a national dress code (the gho for men and the kira for women) to be worn on formal occasions, and the exclusive use of Bhutan’s official language Dzongkha in schools. The directives also extend to cultural institutions, so that art patronage favours practices involving traditional Bhutanese crafts and Buddhist themes rather than more political and secular work; and increased support for Bhutanese folk singers and dancers, particularly at events such as weddings, new year celebrations and sporting events.

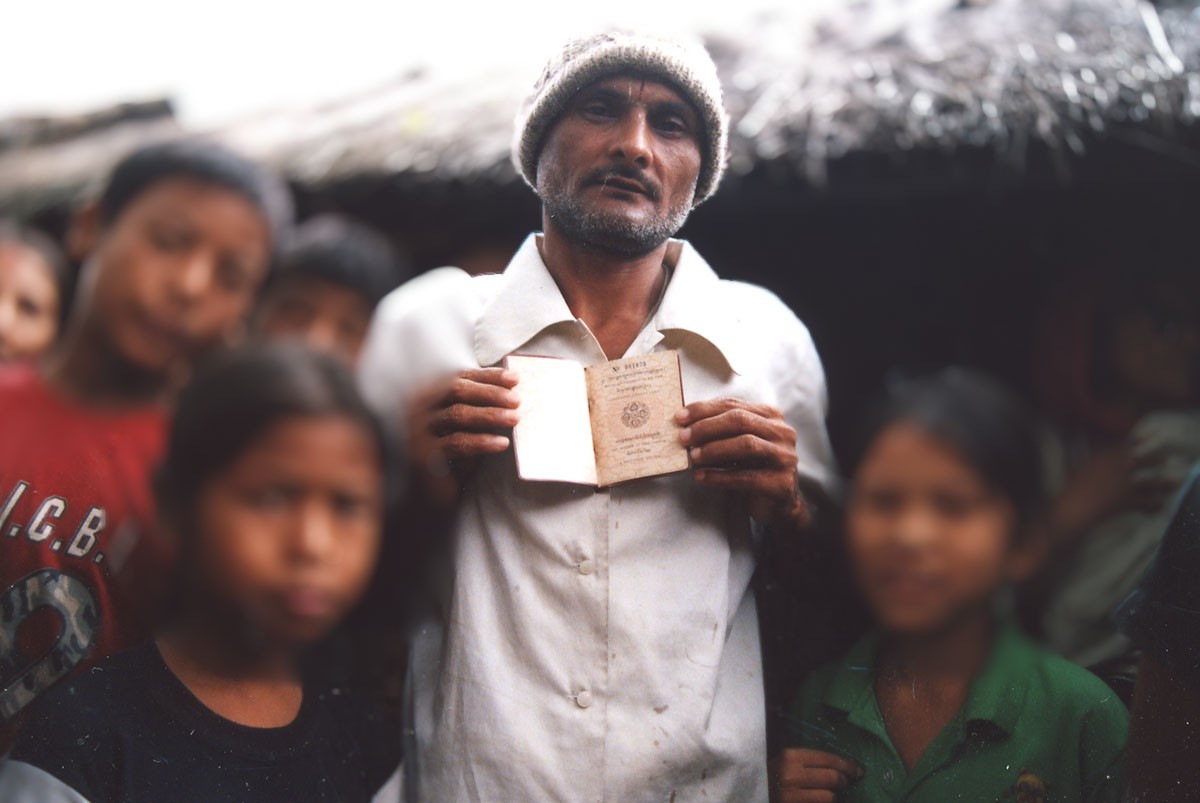

These policies, despite being diluted with later decrees, alienate the country’s ethnic minority — migrants from neighbouring Nepal, locally known as Lhotshampas, who were primarily employed in the construction of Bhutan’s modern infrastructure and other development projects in the twentieth century. This mainly Hindu, Nepali-speaking population differs in key cultural aspects from the majority Ngalop Buddhist people descended from Tibetan settlers who migrated to Bhutan from the ninth century onwards.

In the 1980s the Lhotshampas have also been vocal supporters of democratic reforms in the country, with the goal to push the government towards a constitutional monarchy, in an extension of the concurrent pro-democracy movement in Nepal. The revitalisation of the Driglam Namzha in this milieu is interpreted as an attempt to emphasise Bhutanese nationalism and tradition towards strengthening the position of the Bhutanese monarchy and turning support away from the reformist movement headed by Lhotshampa groups such as the Bhutan Peoples’ Party, founded in 1990 and soon declared a terrorist organisation by the Bhutanese government for its violent clashes with law enforcement. In the early 1990s, many Lhotshampas begin to face accusations of being illegal settlers; they flee Bhutan by the thousands as ethnic violence increases in the country’s south, where most Lhotshampas have historically resided.

Bibliography

Altmann, Karin. Fabric of Life: Textile Arts in Bhutan – Culture, Tradition and Transformation. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2016.

Banki, Susan. “Resettlement of the Bhutanese from Nepal: The Durable Solution Discourse.” In Protracted Displacement in Asia: No Place to Call Home, edited by Howard Adelman, 29–58. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing, 2008.

Bean, Susan S, Diana K. Myers, and Rinzin O. Dorji. “Modeling a Future for Handmade Textiles Bhutan in the Twenty-First Century.” Textile Museum Journal 46, no. 1 (2019): 52–73.

Savada, Andrea Matles. Nepal and Bhutan: Country Studies. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, 1991. https://www.loc.gov/item/93012226/.

Walcott, Susan M. “One of a Kind: Bhutan and the Modernity Challenge.” National Identities 13, no. 3 (2011): 253–66. https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/S_Walcott_One_2011.pdf.

Feedback

This entry appears in

Art in South Asia

Visit Timeline

Associated Timeline Events

First Published: March 11, 2024

Last Updated: August 6, 2024