Encyclopedia of Art > Articles

Manuscript Painting

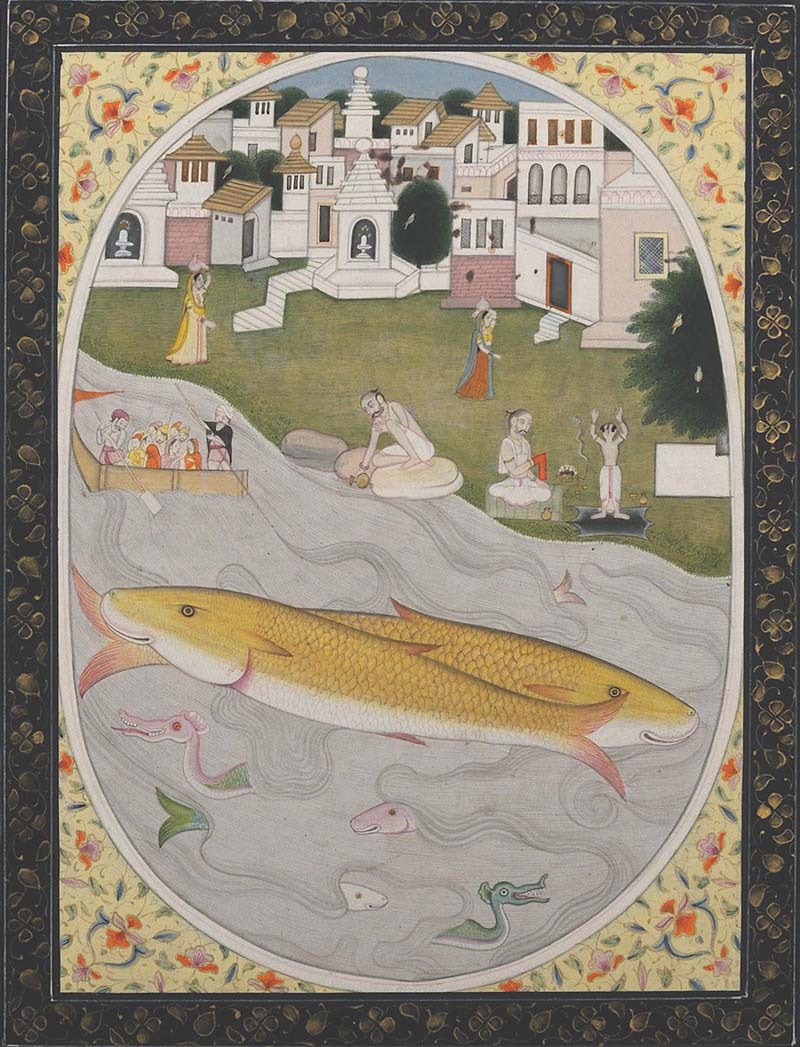

Also called miniature paintings due to their intricacy and small scale, manuscript paintings are the illustrations of key scenes that accompany the text in a range of historical Indian books, including romances, epics, works of fantasy, travel literature, religious texts and biographies. In this sense, illustrated manuscripts are distinct from muraqqas, which were albums of individual painted images made for a patron’s personal perusal.

The tradition of illustrating manuscripts in the Indian subcontinent dates back to the ninth century, or possibly earlier. Historically, most manuscripts were made on commission from wealthy patrons, as a result of which manuscript painting became a major court art during the medieval period in India. In many cases, manuscripts were also used for storytelling performances at these courts, with the image on the front-facing side and the corresponding text on the reverse side of a folio, allowing the performer to check the text as they displayed the illustration to the audience. The systems of producing these manuscripts would vary: in some cases, a single artisan illustrated an entire book, but manuscript painting was typically done by an atelier of at least a few artisans, working under a master painter. Well-established artisans were retained for long periods by particularly wealthy courts with rulers who had a keen interest in the arts, but for the most part artisans worked with clients on a project basis. Teams of artisans divided the work among themselves on the basis of specialisations such as portraiture, patterning, painting costumes and accessories, or the rendering of animals, birds and plants.

While Indian traditions of manuscript painting vary greatly in style, they are typically rendered in a flattened perspective and a variety of colours, with patterned borders featuring floral or geometric motifs. Wherever patterns are included in the painting – such as on a figure’s clothes, upholstery or architecture – these are reproduced evenly as though on a flat surface and rendered with great care to maintain uniformity. Manuscript painting traditions that were directly or indirectly influenced by the Persian style typically have a lighter colour palette, a high horizon line and tend towards naturalism in the rendering of faces, flora and fauna. The intricacy of border patterns, neatness of composition and use of expensive colours such as gold and ultramarine blue are some common indicators of a manuscript painter’s skill and abilities as well as a patron’s tastes and wealth.

The major traditions of manuscript painting in the Indian subcontinent are Pala Buddhist painting in eastern India and Nepal; Jain manuscript painting in western and central India; Mughal and Rajasthani painting in northern and western India respectively; Deccani painting in southern India; and Pahari painting in the kingdoms at the foothills of the Himalayas. In addition to, and often within, these categories smaller kingdoms had their own manuscript painting styles and ateliers, which usually came under the influence of the major schools. Additionally, some notable manuscripts have been found whose makers and patrons remain unknown. Among these are Majuli manuscript painting, Bengal Sultanate manuscript painting, Awadhi manuscript painting, a Jain-style Shahnama, the Nimatnama-i-Nasiruddin-Shahi cookbook, and an illustrated copy of the Chandayana. Apart from imperial patronage, wealthy merchants or noblemen also commissioned manuscripts, although these are more difficult to date and were executed by minor or inexperienced artists. Exceptions to this include the few European patrons who were active in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, though they typically commissioned albums rather than manuscripts.

Manuscript painting in India drew influences from outside as well as within the subcontinent. External influences, which are seen primarily in Deccani and Mughal painting, came from the Safavid court in Persia (present day Iran and Iraq), which had a flourishing manuscript painting tradition from the sixteenth century onwards and became a highly influential cultural presence in Asia as well as the Indian subcontinent. Local traditions of manuscript painting are much older, with some scholars tracing it back to the third or fourth century CE, although the earliest surviving folios date back to the twelfth century and the earliest wooden covers for manuscripts date back to the ninth century. These early folios took the form of narrow, painted palm leaves that were punched with holes and tied together to make books.

In fact, within India, manuscripts were made exclusively with palm leaves until the fourteenth century, when paper began to be used in Gujarat for Jain manuscripts. A paper manuscript, called a codex to distinguish it from the palm leaf variety, became the most preferred medium by the early sixteenth century due to its variable size and capacity to hold a wider range of pigments. The palm leaf manuscripts ranged from ten to twenty inches in length, while the codices could reach up to two feet. The codices also had more ornate borders around the images and some of the text as well, likely as a result of Persian influence. Expensively painted manuscripts, especially codices, often used rare or precious materials as pigment, including gold and lapis lazuli, and the high standard for intricate work meant that artists used fine squirrel hair brushes, sometimes comprising a single strand.

Religious Jain and Buddhist texts were the most common illustrated manuscripts of the mediaeval period before the establishment of Islamic sultanates in India. The wooden covers discovered are speculated to have been made for a now lost Buddhist manuscript from the kingdom of Gilgit in present-day Kashmir. Later Buddhist palm leaf manuscripts that have survived were made at the monastic centres of Nalanda and Kurkihar (present-day Bihar) in the eleventh century, as part of a tradition now referred to as the Pala school. Jain manuscripts, usually religious in nature, continued to be produced well into the sixteenth century in Western and Central India, drawing influences from the emerging painting tradition in Safavid Persia through existing trade links across the Persian Gulf. Jain and Buddhist manuscripts typically gave more importance to the text, with the images playing a largely decorative role. In later traditions, however, both text and image were crafted and patronised to an equal degree.

Pluralism has been a major characteristic of manuscript painting in India, with Jain, Hindu and Muslim patrons and artists creating manuscripts with themes that draw from a wide range of religious and cultural material. As a result, there was a rich and rapid exchange of styles in the subcontinent as artists trained in various schools moved from court to court. Beginning with Akbar’s patronage of the art form in the second half of the sixteenth century, Mughal manuscripts became the most influential style in India, attracting painters and calligraphers from across regions and cultural backgrounds, including some from Persia. Mughal painters were also influenced by Western art and adopted some of its attributes, most notably the more naturalistic aerial perspective. At roughly the same time, the Deccan kingdoms that had broken away from the Bahmani Sultanate in the sixteenth century began commissioning illustrated manuscripts of their own, first in a highly original elaborate aesthetic and then in a more noticeably Mughal style. Although some kingdoms in present-day Rajasthan also began patronising manuscript painters around the same time as the Mughal court, the Rajput style emerged in earnest only by the late seventeenth century, as painters left the declining ateliers of the Mughal court. From the early eighteenth century onwards, Pahari painting flourished as a distinct genre in kingdoms established by Rajput kings in present-day Himachal Pradesh.

By the late nineteenth century, illustrated manuscript painting was largely replaced by photography and large Western-style portraiture. These art forms appealed to rulers of the Princely States under British rule both in a technological and cultural capacity. While illustrated manuscripts are no longer produced, the most recognisable styles of such painting have been adopted by several contemporary artists from Pakistan, most notably Shazia Sikander, Bashir Ahmad, Saira Wasim and Imran Quereshi. In India, miniature painting has also been a major influence on artists of the Baroda school and Bengali modernists such as Nilima Sheikh and Abanindranath Tagore.

First Published: April 21, 2022

Last Updated: July 26, 2023