A traditional form of textile painting for the ritual worship of the goddess is known as Mata ni Pachedi. The craft has been associated with the nomadic Vaghri community of Gujarat which was not allowed to enter the temples since they were a non-dominant caste and had to create their own shrines for worship. The main image in Mata ni Pachedi is that of Hindu goddesses situated within enclosures demarcating a temple. The paintings, quite like the phad tradition from Rajasthan and kalamkari from south India, depict narratives from mythological texts, epics and popular tradition through illustrations. Traditionally Mata ni Pachedi was used as a canopy resembling a ceiling and backdrop in temporary wooden shrines.

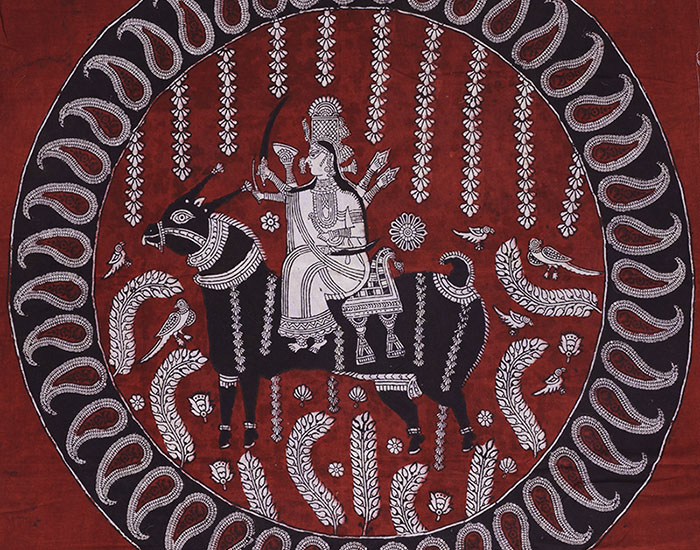

To make Mata ni Pachedi, a rectangular fabric is used, which is then divided into seven to nine columns to create a grid for the narrative to unfold. The grid is structured by almost-architectural insertions that reproduce windows, doors and archways in a stylised form. Earlier, the colours used were naturally procured and processed and consisted of a visual scheme of masoor (red) and black on a white cloth: black was extracted from jaggery, iron rust and water and red from alum, alizarin, tamarind and dhawadi flowers. Before painting, the cloth is soaked, washed, de-starched and treated with a harda (terminalia chebula) solution. Both wood-block printing and hand-painting are used to paint the fabric. While wood blocks are usually used for the borders, many drawings, embellishments and motifs are painted with a bamboo kalam (pen). With the ready availability of artificial textile colours and high demand during Navratri, when Mata ni Pachedi is elaborately decorated, the artists have now switched from natural colours to speed up their process.

In Mata ni Pachedi the central figure of the goddess has a commanding presence. She is flanked on her sides by worshippers, musicians and animals. The many forms of the goddess – known through mythological and oral narratives, textual sources and popular local traditions – are found in this textile including Durga and Ambe. Also included are goddesses from the local folk culture of Gujarat, such as Vishat Mata, one of the most important goddesses for the Vaghris (it is believed that the community descended from her); Vahanvati Mata, who is worshipped by seafarers and traders; Momai Mata, more popularly known as Dashamaa, a goddess of the Kutch region and protector of health, livestock and harvest; Khodiyar Mata, who is known to be powerful enough to predict the nature of incoming monsoon; and Hadkai Mata, who protects her flock from rabies. The defining presence of the local goddesses in the textile not only records a religious tradition but also offers a glimpse into the social and cultural life of the Vaghris, the precarity of a nomadic and agricultural community, dependence on yearly monsoon rains and the naval trade along the coastline of Gujarat.

In Mata ni Pachedi the goddesses are depicted according to their iconographic aspects. In some variations, the Hindu god Ganesh appears in either the upper portions of the cloth or to the left of the goddess. Narratives from Mahabharata and Ramayana also find a portrayal where the artists improvise the scenes to suit the form of textile painting. For instance, it was difficult to render the golden deer (from the scene of Sita’s abduction in Ramayana) in colour so the artists depicted it as two-headed. Similarly, the game of dice from Mahabharata was substituted by a game of cards which is easier to portray.

The need to improvise and adapt the form has led to significant changes in the art; the grid-like structure for the narrative is no longer a requirement and traditional depictions of rows of worshippers carrying garlands and flags have been supplemented by angels carrying them. In some cases, the temples appear to be domed like mosques. The art has also incorporated a vast array of artificial colours including sap green, yellow ochre and indigo.

The popularity of Mata ni Pachedi is no longer restricted to its ritual aspect and its significance during Navratri. Artists now produce decorative consumer goods such as bed sheets, pillowcases, wall hangings and garments in the textile’s traditional style.

First Published: April 21, 2022

Last Updated: July 26, 2023