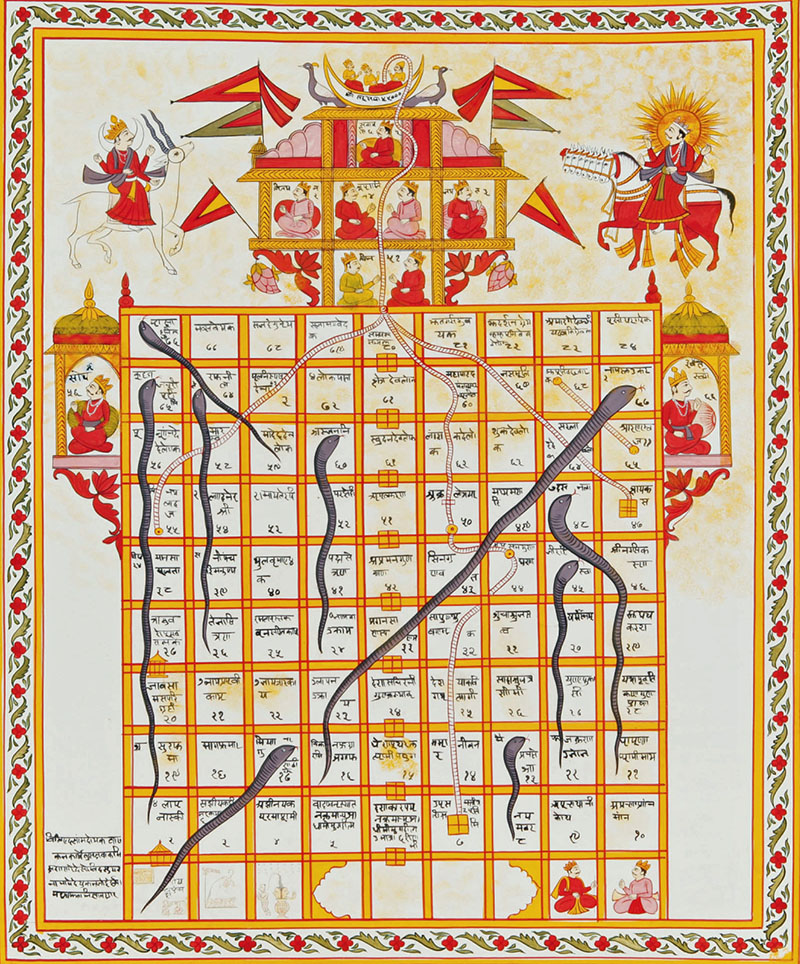

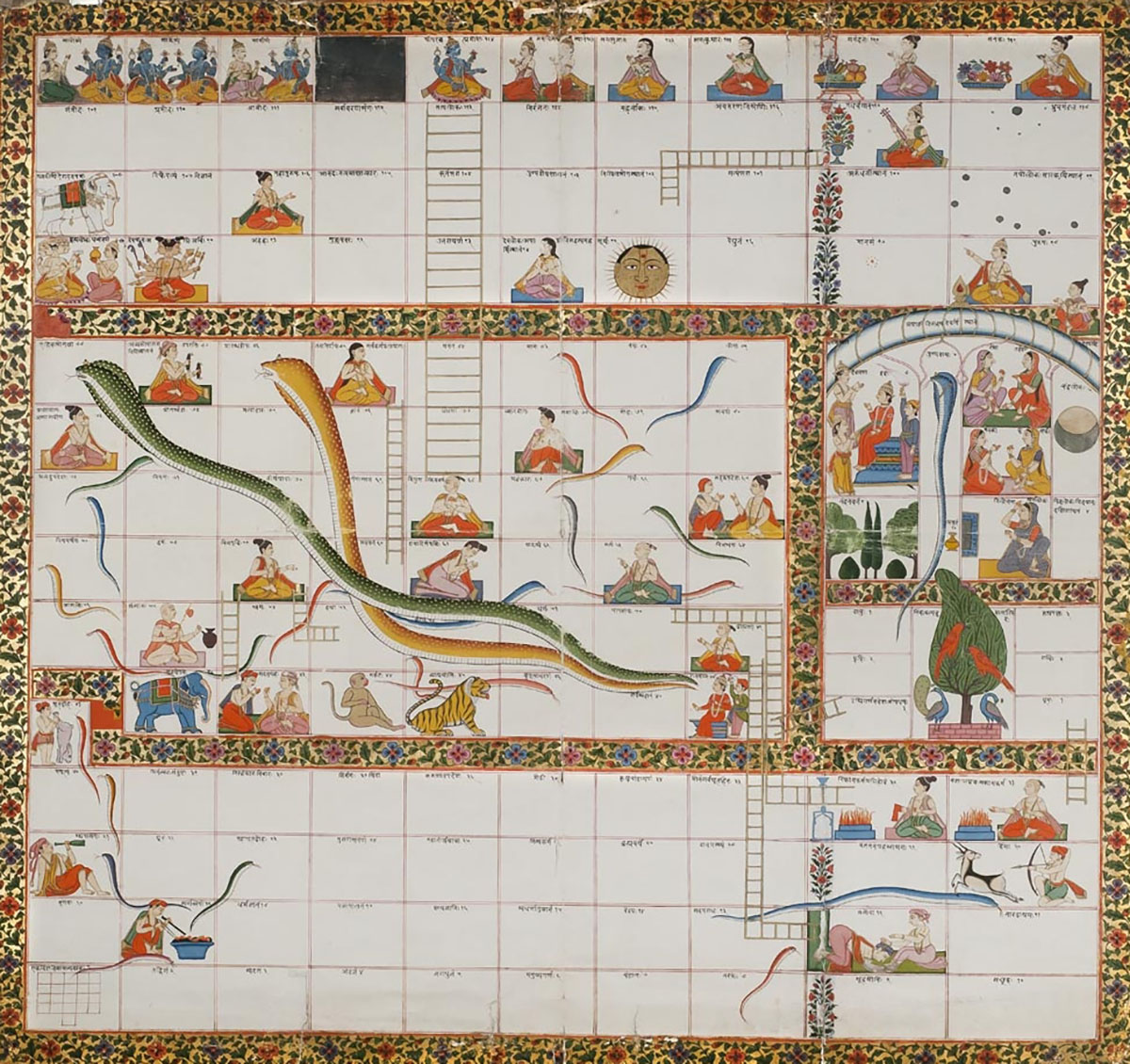

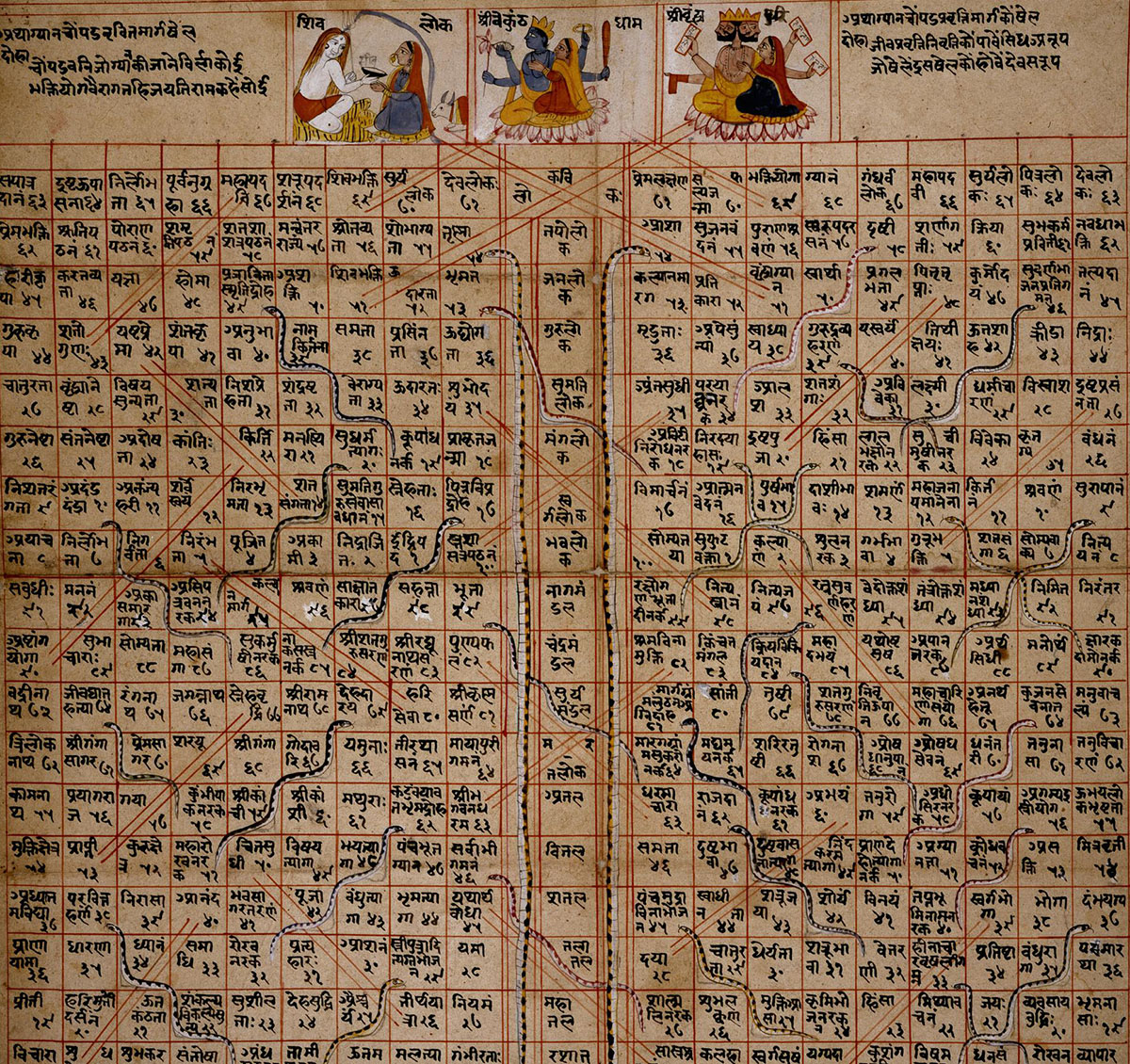

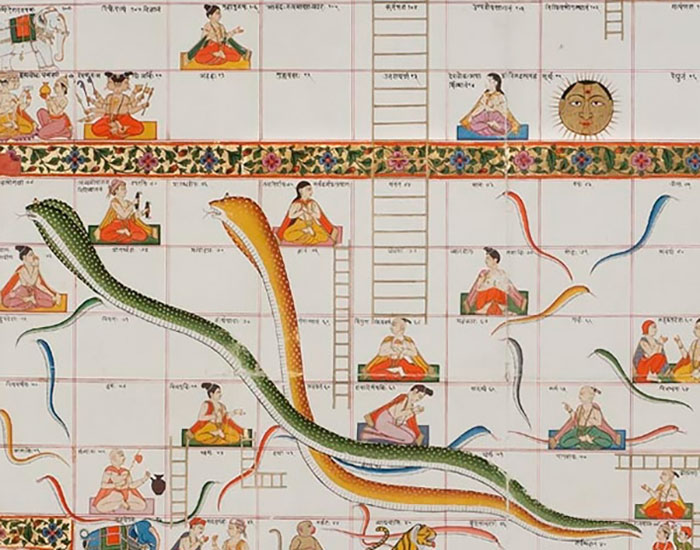

Also known as Gyan Chaupar, Moksha Patam is a board game dating back to mediaeval India. It was traditionally played on a board made of cloth, featuring a series of squares, snakes and ladders. Some more elaborate boards included additional imagery, such as portraits or decorative borders.

The origins of Moksha Patam remain a matter of debate, with some scholars attributing its invention to Dnyaneshwar, a thirteenth-century Marathi saint, while others interpret a passage from the tenth-century text Rishabh Panchasika as an even earlier reference to the game. The oldest surviving example of the game is from seventeenth-century Mewar.

The gameplay of Moksha Patam was as follows: each player has a token and moves between numbered squares from the bottom to the top of the board, according to the roll of the dice. The board contains images of snakes and ladders, which function as conduits between squares on different vertical levels: if a token lands on a box at the head of a snake, it must immediately descend to the box containing the snake’s tail, and if it lands at the foot of a ladder, it may ascend to the topmost rung. The objective of the game is to reach the last box at the top and exit the game.

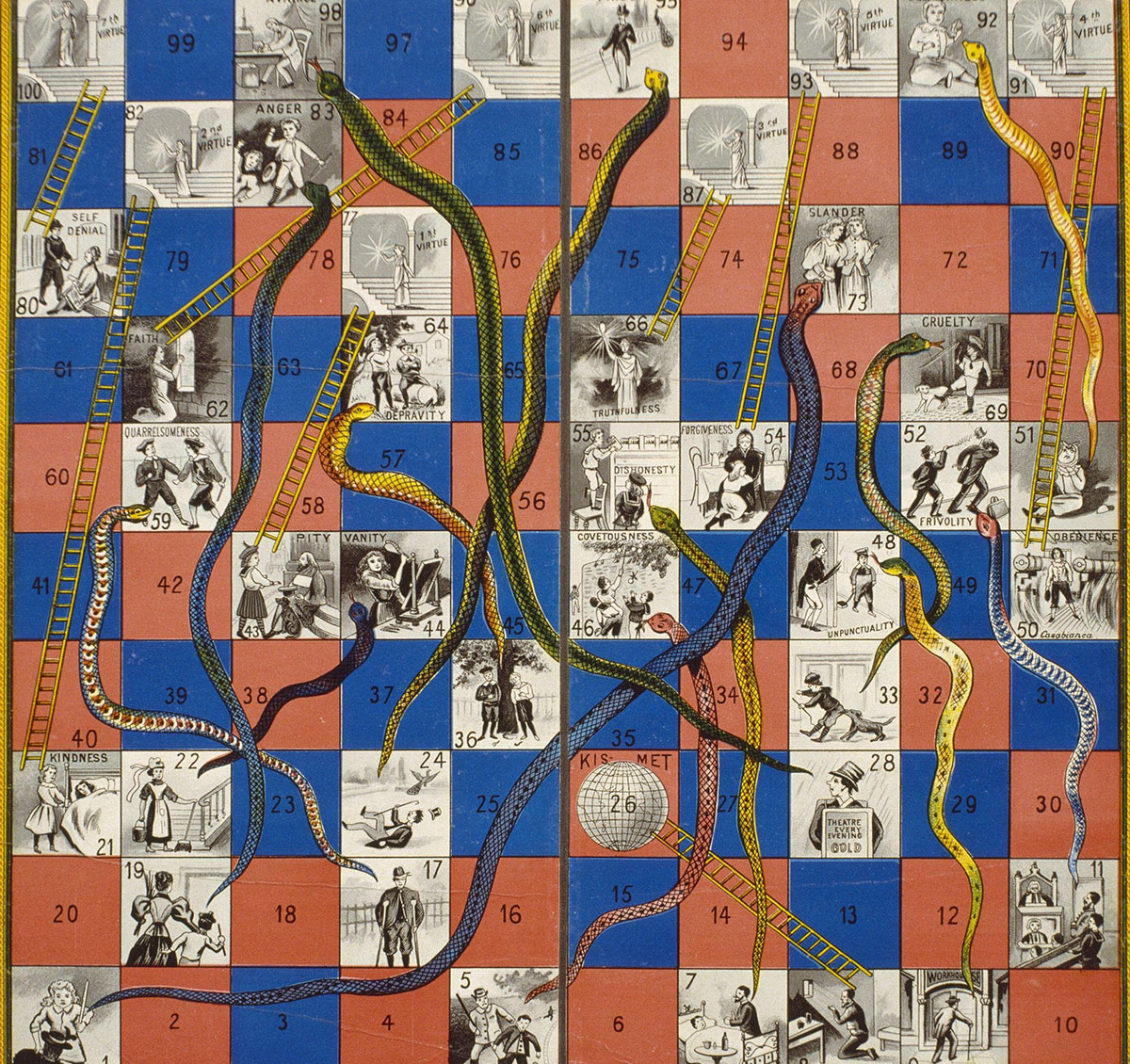

In addition to being a form of recreation, the traditional Moksha Patam had a spiritual and didactic purpose. The last square of the game represented the attainment of moksha or release from the cycle of death and rebirth. The snakes and ladders on the board were meant to function as karmic devices, either thwarting or aiding a player’s efforts to reach moksha. To emphasise this, the squares from which the tokens either ascended or descended were labelled with names of various virtues or flaws. The positive attributes listed were dependability, asceticism, faithfulness, generosity and knowledge, while the negative attributes and crimes were rebelliousness, vanity, crudeness, theft, lust, debt and violence, to name a few. The game, as a whole, was meant to educate players on which personality traits were morally desirable and which were repugnant. The number of snakes was typically much larger than that of ladders — often twice as many — to underscore the difficulty of the path to enlightenment.

In the 1890s, Moksha Patam made its way to Britain, where it eventually acquired the name Snakes and Ladders. While the British version retained some emphasis on ideas of morality – with illustrations of good and bad deeds on the squares that bookended each ladder or snake – it did away with the spiritual connotations and nuances of the Indian version. Later, in 1943, the game was introduced in the USA by Milton Bradley under the name Chutes and Ladders, as the company felt that the image of snakes would scare children away. Other versions of the game include Leiterspiel, a German version that used pictures of circus animals.

Although the modern version of the board has been standardised as a hundred squares arranged in a rectangle, the mediaeval Moksha Patam varied widely in design, containing anywhere between 72 to 124 squares, arranged in a cross or in a custom shape that followed a theme. For instance, in a Mewari board that is housed in the National Museum, the playing area is shaped like a Rajput fort. Some versions of Moksha Patam made for Hindus featured Vaishnavite imagery and labelled the last square as Vaikuntha, or the abode of Vishnu. Gyan Chaupar, as the Jains called Moksha Patam, was especially popular during the period of Paryushan, when devotees fasted and played the game as a form of spiritual engagement. Some Gyan Chaupar designs depicted the playing area surrounded by an image of the Cosmic Being or Lok Purusha. To a lesser extent, versions of Moksha Patam were also made using Islamic or Sufi references, with the last square denoting the moment of merging with God.

Moksha Patam boards from mediaeval India are housed in the collections of the National Museum, New Delhi; the Rajasthan Oriental Research Institute, Jodhpur; the Calico Museum of Textiles, Ahmedabad; and the British Library, London, UK.

First Published: April 21, 2022

Last Updated: July 26, 2023