An embroidery tradition historically practiced and inherited by the women of Punjab in India and Pakistan. Literally meaning “flower work,” phulkari is a counting-thread embroidery recognised by its neat, regular patterns of geometric and natural motifs. Embroidery is traditionally considered an integral skill for women in the region, and phulkari garments are closely associated with major events in their lives, particularly marriage. In the medieval and colonial periods, girls would initially learn to embroider small garments like odhinis for themselves, and as they grew older, produce chaddars to be handed down to younger generations of women in their families. Phulkari shawls are often gifted on wedding days, especially by maternal relatives.

The origin of the craft is debated, with some scholars suggesting that it was introduced to India from Central Asia by the Jat community in the late medieval period, while others state that the craft was born of influences from Persian gulkari embroidery designs. Phulkari embroidery and the traditions surrounding it have been mentioned in the Sikh holy book, the Guru Granth Sahib, and the eighteenth century Punjabi epic Heer Ranjha.

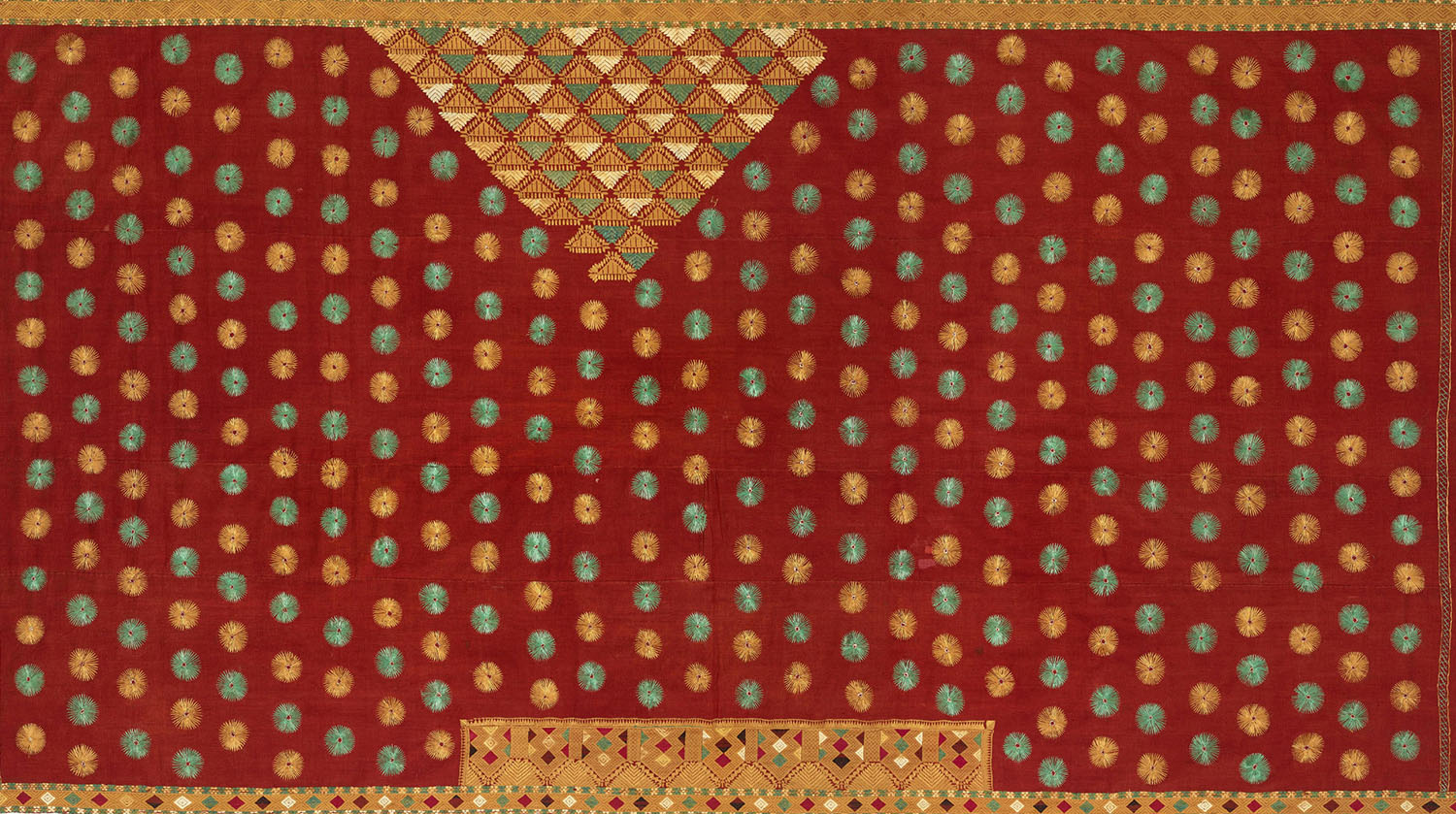

The coarse, handwoven cloth used for phulkari embroidery is called khaddar (or khadi), and is prepared by stitching together strips of heavy cotton fabric that are less than two feet wide. In most cases, the khaddar was traditionally dyed red using plant-based dyes obtained from palash flowers, madder or the bark of acacia trees. Earthy colours like green, brown and yellow are less frequently used, and blue relatively rarely. Phulkari embroidery is done using a running stitch with brightly coloured untwisted silk thread historically imported from Kashmir and Bengal. The floral imagery used in phulkari includes marigolds, jasmines, lotuses and Tree of Life motifs. Despite its name, phulkari embroidery usually depicts animals and geometric forms as well as flowers. Modern motifs such as trains, trucks and cars have also found their way into phulkari patterns.

The counted thread method lends phulkari designs a floral symmetry. In some cases, the embroiderer deliberately breaks the geometrical pattern in a small area, exposing the base fabric below. These are known as nazarbuti motifs and are meant to ward off misfortune for the wearer.

The shawls and wraps traditionally made with this craft are also called phulkaris, as the embroidery is their main feature. There are various types of phulkari, distinguished by their size, style and ceremonial value. Thechhope, made with a reversible, double darning stitch, is the largest and has the most ritual importance in Punjabi culture, as it is embroidered by a bride’s grandmother, presented as a wedding gift and worn during the marriage ceremony. Others include the sainchi phulkari from the Bathinda and Faridkot districts; the blue nilak phulkari embroidered in red and yellow; the thirma phulkari made on a white base; the shishedar phulkari embellished with glass pieces; the til patra phulkari made with patterns of sesame seed motifs; and suber phulkari, which is embroidered only in the corners. Bagh embroidery, which uses an all-over design where the base is completely obscured, is sometimes regarded as a type of phulkari, but this and its subtypes are distinct textiles.

Until the colonial period in South Asia, phulkaris were not produced for commercial purposes and were circulated in what is now Pakistani Punjab, mainly in the Peshawar, Sialkot, Hazara, Rawalpindi and Jhelum districts. From the nineteenth century onwards, embroidered shawls began to be given to British officers as tokens of goodwill. This period also saw the beginning of the commercial application of the craft on other garments, such as coats for women customers living in cities. Following the Partition and the subsequent political turmoil in Punjab, phulkari embroidery went into a decline in India and Pakistan through the 1950s.

Concerted efforts by both governments, in the form of classes and mechanisation, helped reduce the labour of preparing the khaddar and obtaining the silk embroidery thread. Artisans were given financial support from banks and other government organisations like the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD), Khadi and Village Industries Commission (KIVC), the Ministry of Textiles and the Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI). From the 1980 onwards, fashion designers and NGOs like the Nabha Foundation have also played a major role in supporting local artisans by expanding the market presence of phulkari embroidery and design.

Today phulkari is produced mainly in Gurdaspur and Patiala, India, and is applied to several types of Indian garments, particularly dupattas, kurtas, blouses and sarees, using various cotton fabrics as a base.

First Published: April 21, 2022

Last Updated: July 26, 2023