Encyclopedia of Art > Articles

Rajasthani Manuscript Painting

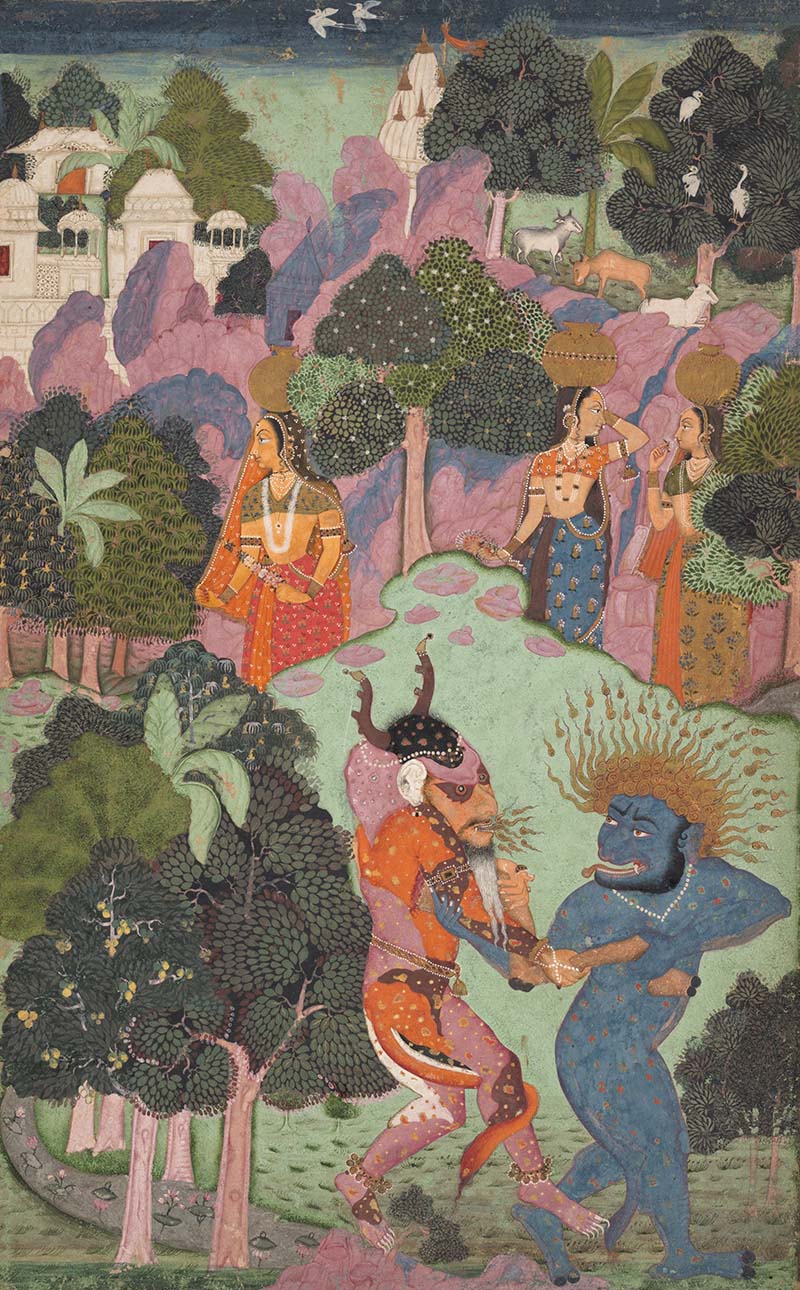

The traditions of manuscript painting that emerged in the Rajput courts of central and northwestern India between the sixteenth and the eighteenth century are collectively referred to as Rajasthani manuscript painting. Imbibing elements of naturalism, as well as Mughal and Islamic influences, these paintings were characterised by flat compositions, the use of black outlines, pointed facial features and a bold colour palette.

The earliest examples of painted narratives from the region – which comprises the present-day states of Gujarat and Rajasthan – are the palm leaf manuscripts of Jain texts, which were stored in bhandaras, or libraries. By the fifteenth century, secular and Hindu religious manuscripts also began to appear, including illustrated versions of the Gita Govinda, the Devi Mahatmya, the Panchatantra and the Rati Rahasya. Despite their use of paper, these texts retained the restricted, horizontal format of palm leaf manuscripts. The illustrations themselves are characteristic of the Western Indian style of painting, featuring saturated colours, angular silhouettes, protruding almond-shaped eyes and faces depicted in three-quarter profile.

By the mid-fifteenth century, a stylistic shift was precipitated by the growing influence of Persian and Islamic court art, with Jain manuscript paintings from this period incorporating elements such as decorative borders as well as embellishments like silver, gold and lapis lazuli. An illustrated Bhagavata Purana from this period also reflects the influence of Islamic codexes, with images becoming independent of text and expanding in size, sometimes occupying the entire folio. Another significant evolution was the development of an early Rajasthani style, also known as the Chaurapanchasika style, which derived its name from a group of sixteenth-century poetry manuscripts.

During the Mughal era, Rajasthani manuscript painting developed in the Rajput courts of the region, in workshops that were likely inspired by their Mughal counterparts. The Mughal techniques of naturalism in landscape and physiognomy, spatial depth and perspective, were absorbed to differing degrees in these courts and co-existed alongside their own traditional styles. The themes of the manuscripts from this period were diverse, encompassing religious texts such as the Bhagavata Purana, epics such as the Ramayana and Mahabharata, as well as legends and stories about local folk heroes. Works about the life of Krishna, in particular, were popular and produced across the different royal courts. Poetical works such as Rasamanjari, Rasikapriya were also commissioned, as were devotional works like the Gitagovinda and Sur Sagar.

Each Rajput court across the region had its own legacy and style of manuscript painting. These were not always limited to royal workshops. In Marwar, for example, a Meghaduta manuscript was commissioned by lay patrons in 1699 and was stylistically similar to a traditional Ragamala series dating back to 1624. At Mewar, which was another prominent school of miniature painting, the earliest manuscript, Chawand Ragamala, dates back to 1605. It is one of several notable works produced by the court’s workshop during the first half of the seventeenth century, including the Mewar Ramayana (1649–53). The central Indian region of Malwa already had a longstanding manuscript painting tradition, now known as the Malwa school of painting. After the fall of its capital, Mandu, in the second half of the sixteenth century, the smaller Rajput principalities of the region kept its tradition of illustrated manuscripts alive.

In the seventeenth century, the style of the Bikaner school continued to parallel the Mughal artistic style of the time. However, by the second half of the century, the Mughal workshops suffered a decline and its local painting tradition re-emerged and gained prominence, as evidenced by a Rasikapriya series and Bhagavata Purana dating to this time. During the same period, manuscript painting was also flourishing in the workshops or chitrashalas of Bundi and Kota. The former is notable for its use of elements from both the Mughal and the Deccani schools. The latter, after its separation from Bundi, established its own painting tradition, which included detailed depictions of landscapes and hunting scenes in addition to devotional works.

The apogee of the Kishangarh school, meanwhile, came in the first half of the eighteenth century, characterised by devotional paintings of Radha and Krishna. These paintings, primarily executed by the master artist Nihal Chand, were based on the Bhagavata Purana, the Gita Govinda and the poems of Savant Singh, the then ruler of Kishangarh. In the court of Amber at Jaipur as well, court painting gained prominence in the eighteenth century, with several manuscripts produced under the royal patronage of its ruler Savai Pratap Singh, including a Ragamala series and a Rasikapriya series.

Like many manuscript painting traditions in the subcontinent, the administrative and economic policies of the British Crown in the nineteenth century led to a decline in patronage as the wealth of most smaller courts was reduced. Coupled with the arrival of photography, which attracted the interest of royal patrons, and new forms of employment for artists, such as Company Painting, Rajasthani and other miniature painting traditions faded away by the late nineteenth century.

First Published: April 21, 2022

Last Updated: July 26, 2023