Encyclopedia of Art > Articles

Somnath Hore

Born in Barama village of Chittagong in present-day Bangladesh, Somnath Hore was an influential artist, known for his paintings, sculptures and innovations in printmaking, through which he explored themes of war, starvation and human suffering.

Hore’s early years were marked by personal hardship and socio-political turmoil. He witnessed a series of tragedies, starting with the death of his father when he was thirteen, the Japanese bombing of a village near his hometown in Chittagong in 1942 and the Bengal famine of 1943 — impressions of which he carried into his adulthood. He was a sensitive child and a bright student. He completed his Intermediate (I.Sc) from Chittagong College, then pursued his bachelor’s degree at City College, Calcutta (now Kolkata). Although he had a talent for art, filling his sketchbooks with observations from his life and surroundings, it remained a private hobby until his encounter with the Communist Party of India (CPI) while in college. Swayed by their rhetoric, he began volunteering with them by creating campaign posters. His art therefore began as much as an expression of his political affiliation as a response to his socio-political environment.

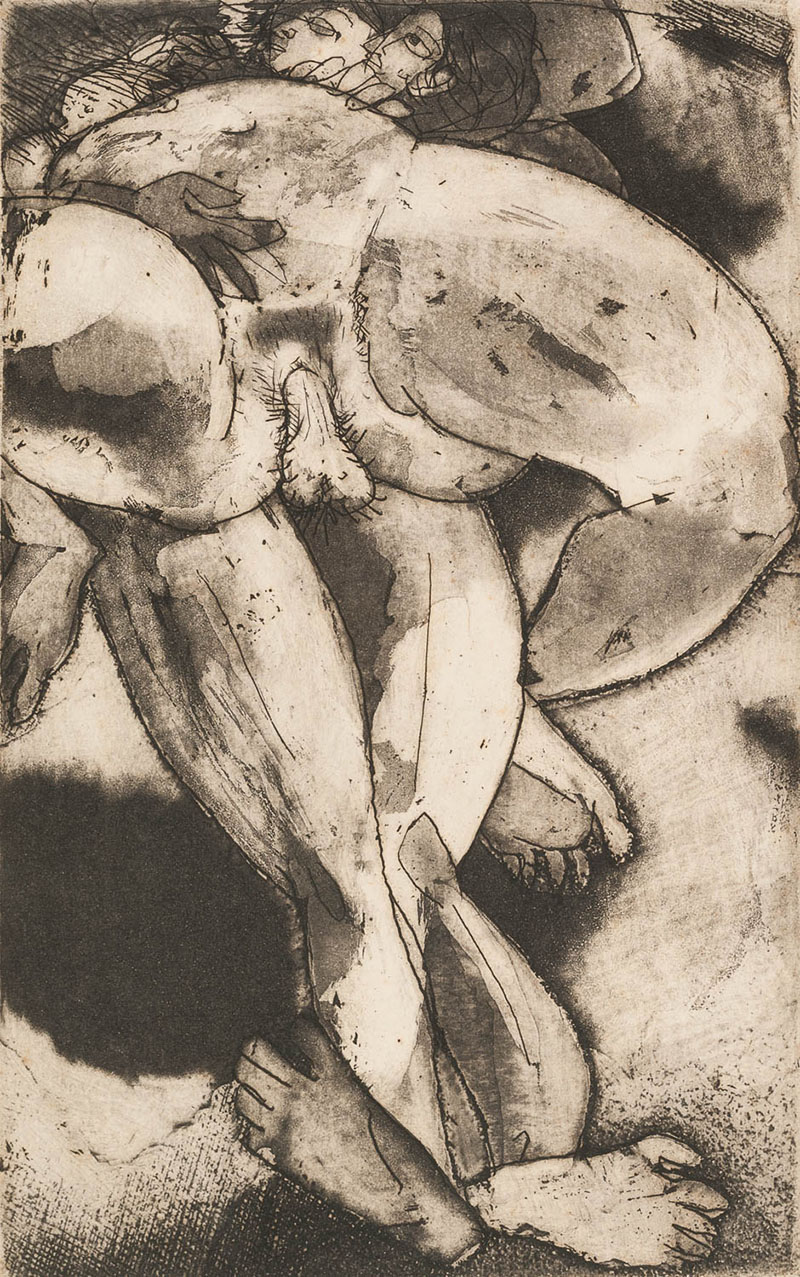

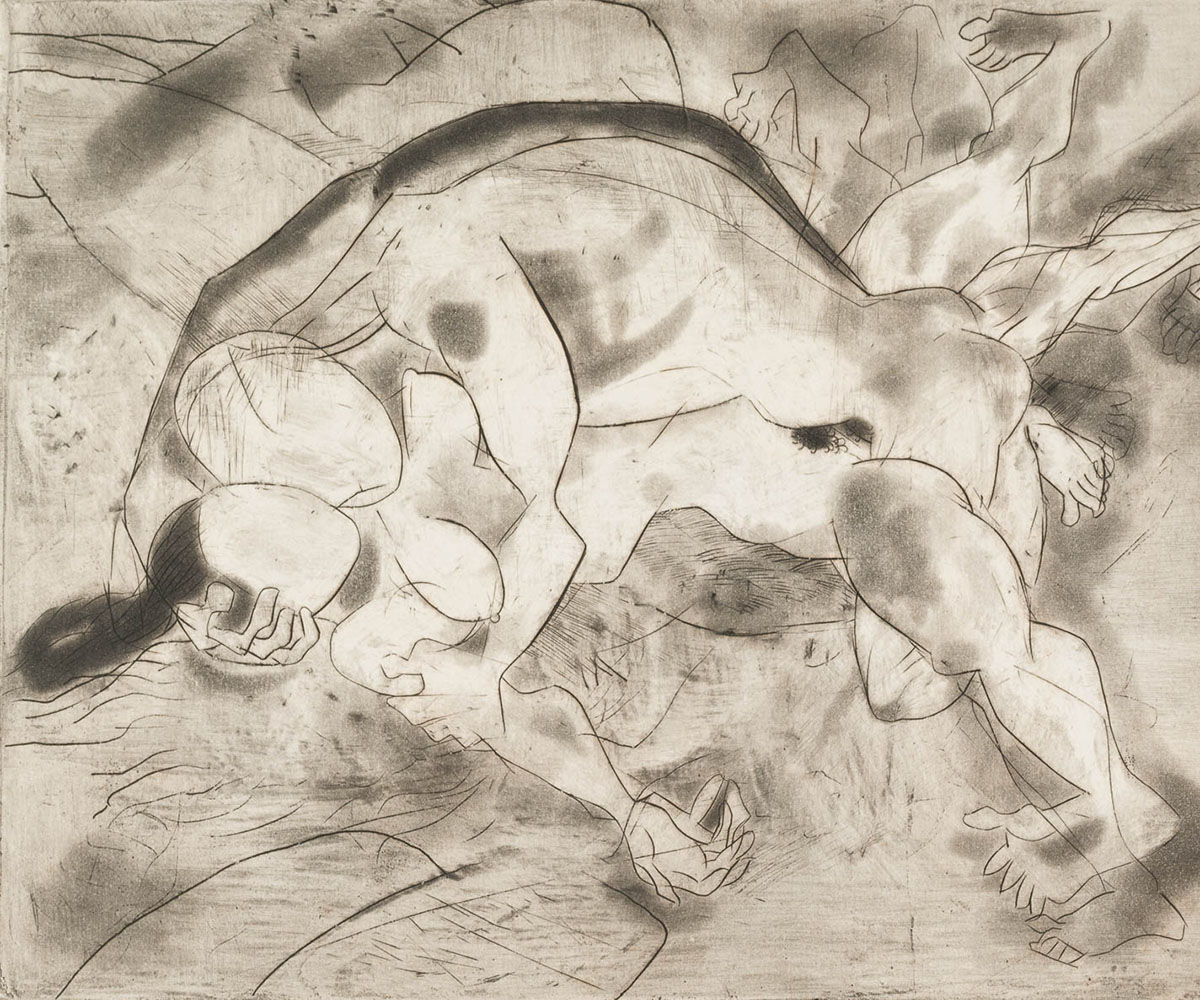

Dropping out of college, he joined the CPI as an artist-cadre and began touring the famine-hit districts of Bengal from 1943–44 to provide visual reportage for the Jannayuddha (People’s War) communist journal. During this period and after the highly charged Tebhaga movement (1946–47), Hore began producing a large number of sketches (several published in Tebhaga Diary) and prints, inspired by the work of his comrade and fellow artist Chittaprosad. In 1945, he gained admission into the Government College of Art and Craft, Calcutta, having been encouraged by the CPI to hone his artistic talents. Here, he trained in the techniques of printmaking and lithography — while also developing his own pulp-print technique, and graduated in 1947 with a diploma in fine arts. His work during this time included a series of woodcuts, prints and sketches that were inspired by the styles of Chinese Socialist Realism and German Expressionism. A few years after completing his formal education, Hore briefly returned to politics; however, his sensitivity to the horrors of famine and the war-stricken humanity that surrounded him eventually drove him back to his artistic practice.

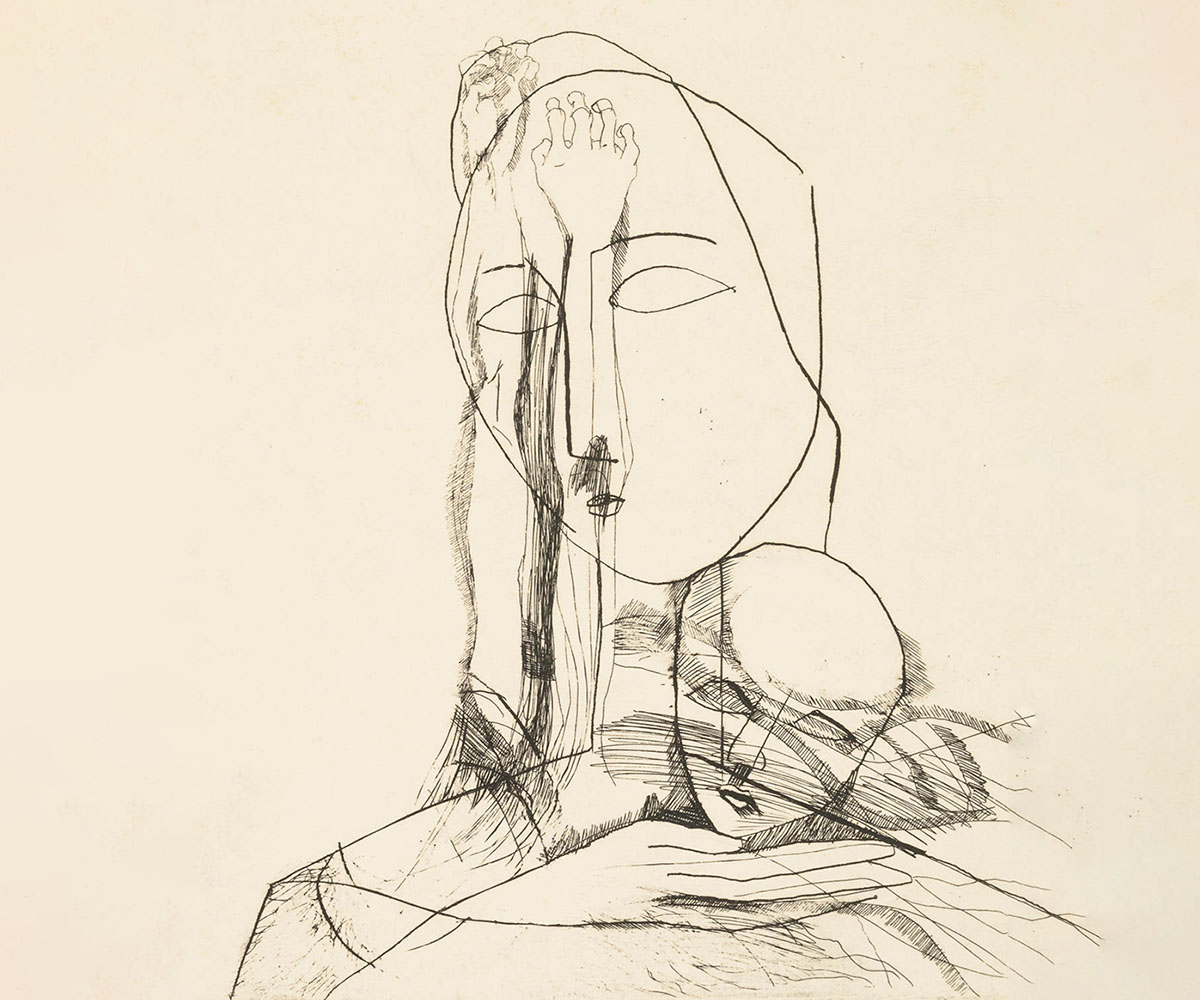

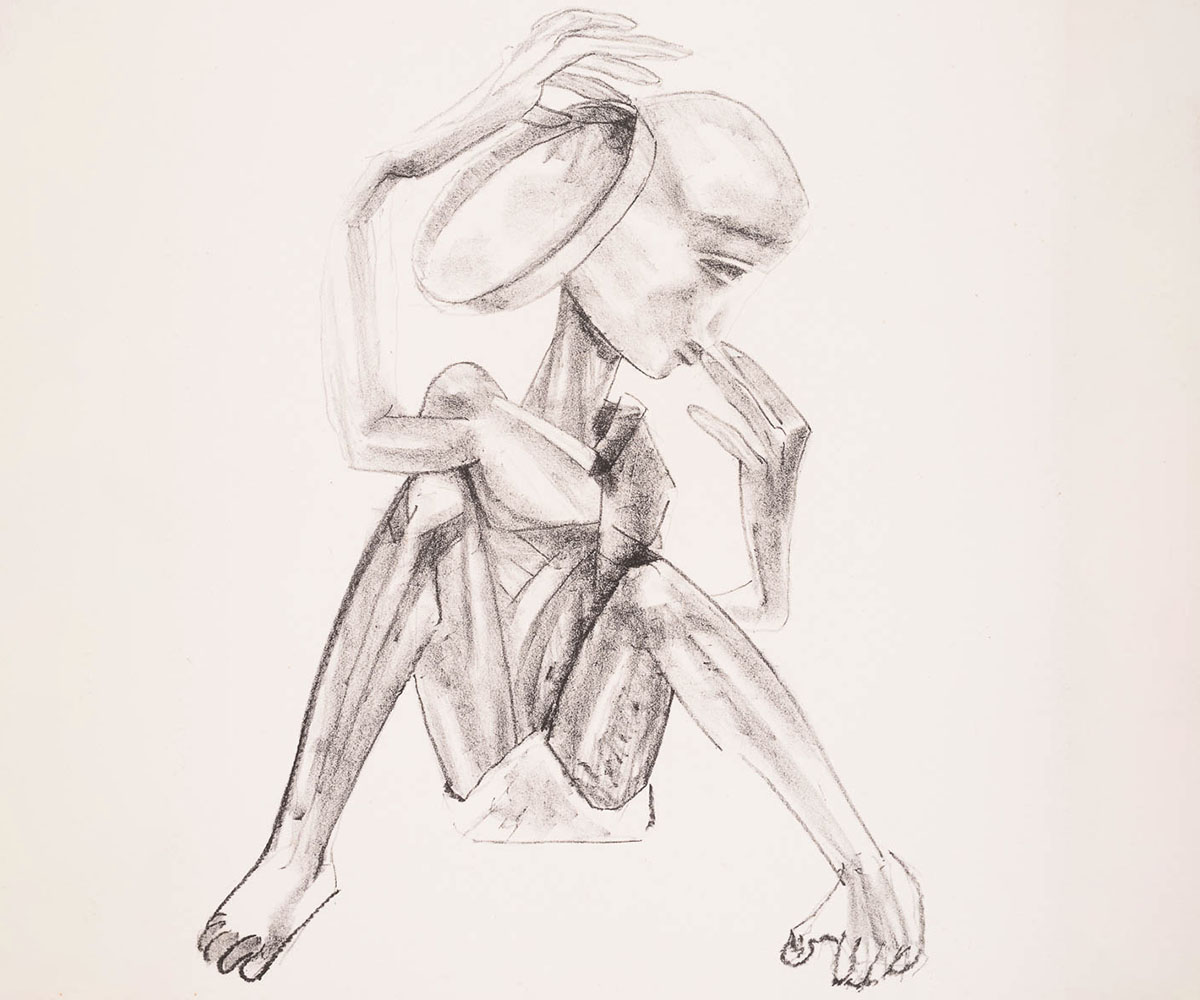

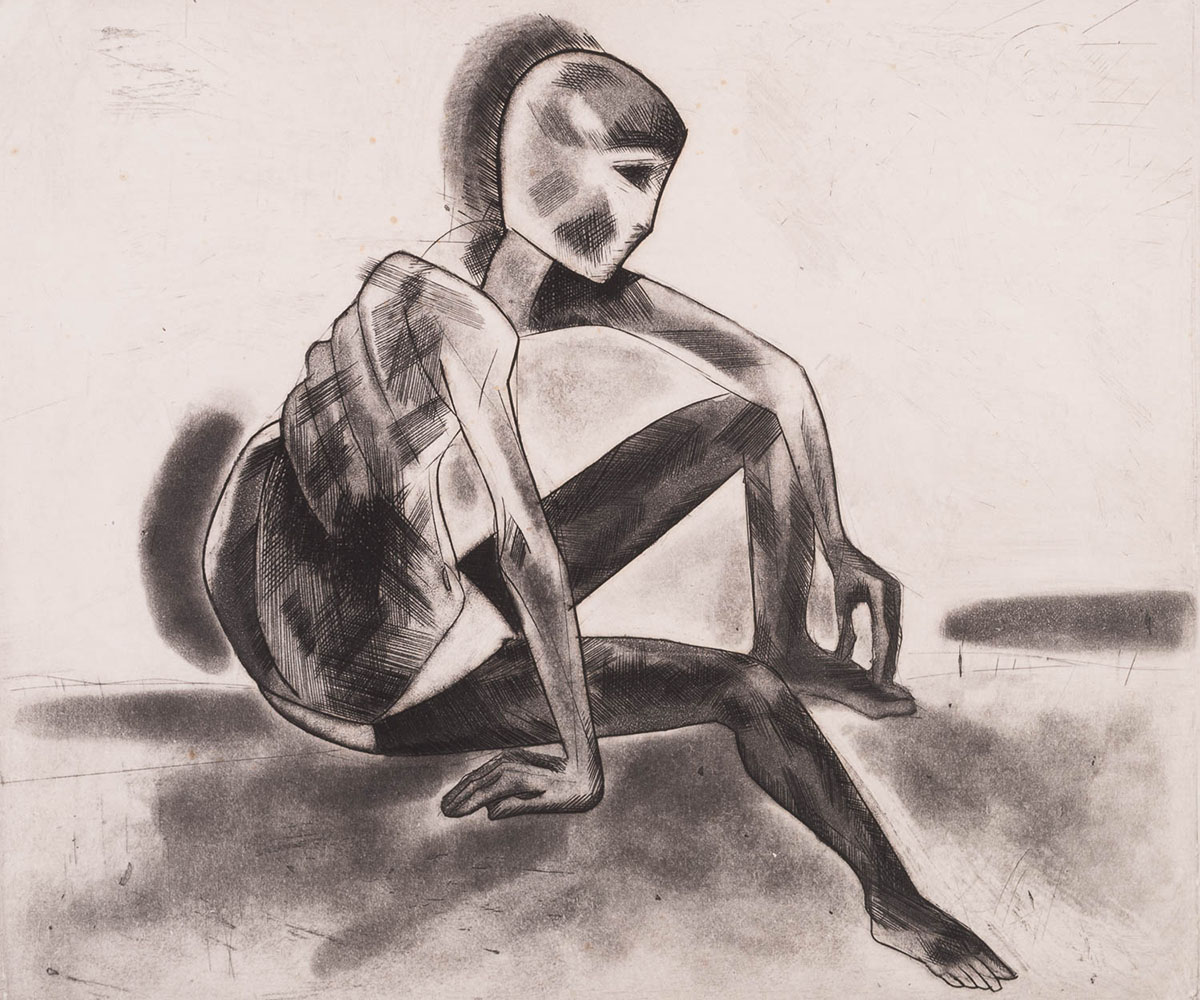

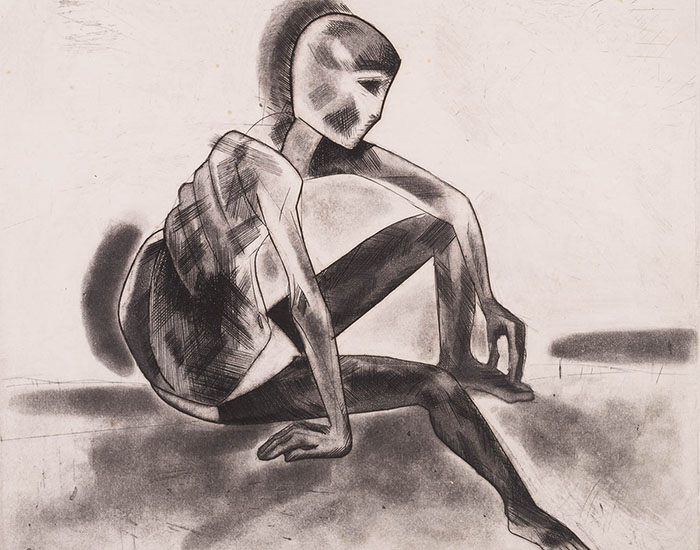

Taking charge of the graphic division of the Indian College of Art and Draftsmanship, Calcutta, in 1954, he began experimenting with intaglio with the desire to build a set of technical skills with which to express his angst at the unfolding scenes of suffering and socio-political strife. While initially preoccupied only with the message of his art, he turned his attention to pictorial language and style when form and content alone no longer felt adequate as vehicles of expression. This led to his tentative exploration of abstraction, best typified by the untitled etching of a sitting figure dated to 1956. Two years later, after having adopted printmaking as his principal medium of expression, Hore joined the Art Department of the Delhi Polytechnic as faculty and supervisor of the printmaking section. For the next ten years, he continued perfecting techniques such as lithography and etching, and carried out both technical and stylistic experiments by juxtaposing form, motif, colour, line and texture. In 1968, he returned to Bengal to head the graphics and printmaking department at Kala Bhavana. While there, he returned his focus to paper-making and paper-based techniques using rag-paper and papier-maché, readmitting the possibilities that other mediums and techniques offered.

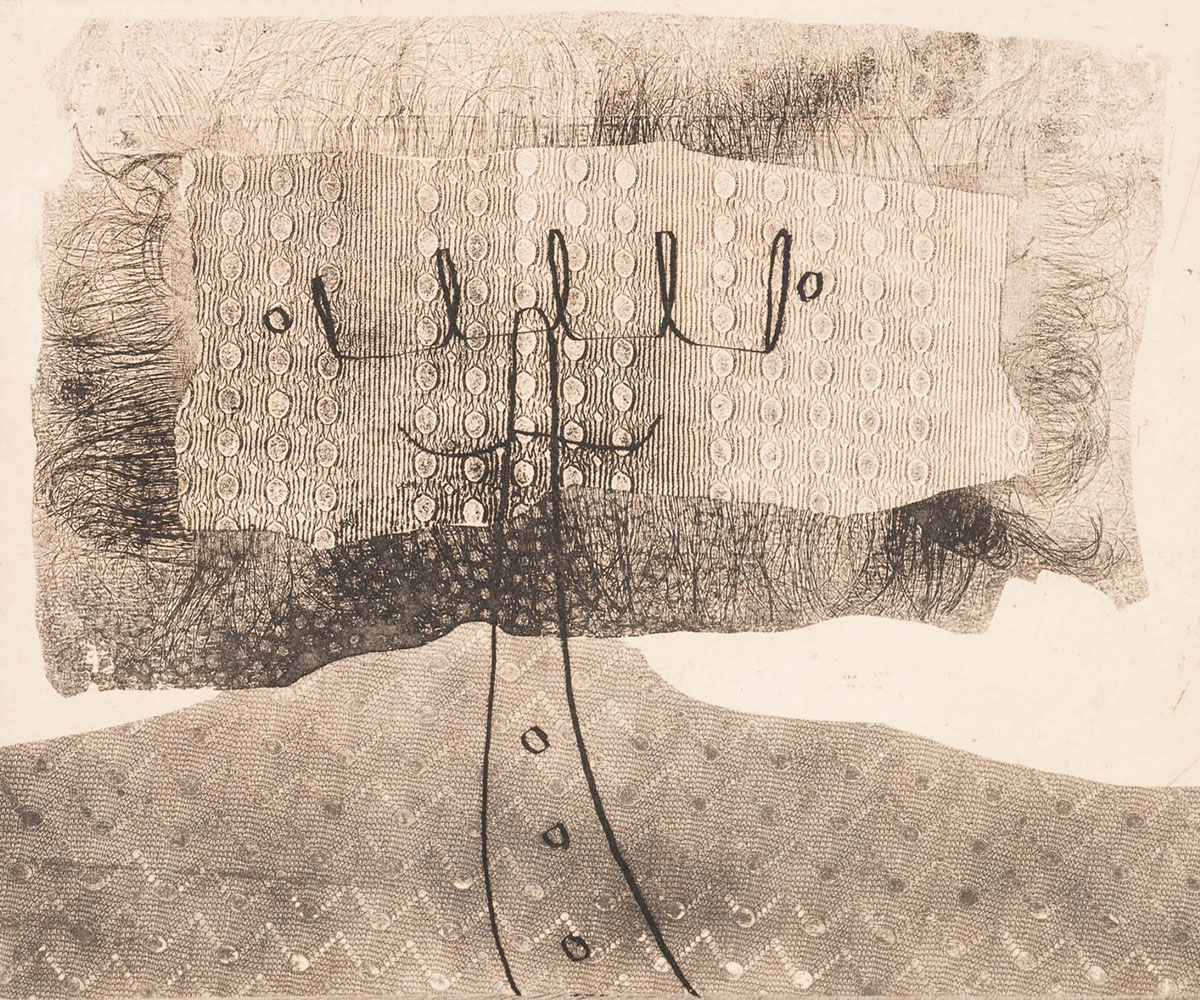

Hore’s earlier explorations in abstraction in terms of colour planes, logography, calligraphy and texture led to a subsequent and decisive shift in his practice in the early 1970s. His expertise in paper pulp-making techniques culminated in the production of his Wounds series (1970s). Through these mostly monochromatic compositions, Hore revisited themes of violence and trauma, which had come to inhabit much of his art. He used hot knives and rods to slash into pieces of clay, which were then used as moulds for his paper pulp. This resulted in prints that had scarred, ripped, dented, torn and blistered surfaces, symbolising the wounds on human skin inflicted by violence and strife. In some cases, Hore traced the contours of the surfaces with red ink to provide an illusion of real blood.

Starting in the 1970s, Hore also began creating bronze sculptures of tortured and skeletal human and animal figures that reflected his lifelong concern with socio-political depredation. Gaunt, starved and half-dead or dying figures remained the central and guiding motif of his sculptural practice, which he pursued to the end of his long and varied artistic career. So universal was his thematic concern and so profound his own reaction to war that one of his largest works transcended national borders. Created in the backdrop of the anti-Vietnam War protests in which Hore himself was an active participant, his Mother and Child (1977) sculpture — 1-metre tall and weighing 40 kilograms — was in some ways the culmination of his deeply sensitive and socially responsive art. However, this tribute to the victims of the Vietnam war, which he spent two years making, remained in obscurity as it was stolen from Kala Bhavana almost immediately after its completion and never subsequently retrieved. The work of his preceding and succeeding years however found their way to various shows, exhibitions, galleries and collections, where they remain to this day.

Some of prominent Indian venues that have displayed Hore’s works are Birla Academy of Art and Culture, Kolkata; NGMA; Jehangir Art Gallery, Mumbai; the Kerala Lalithakala Akademi and Durbar Hall Art Centre, Ernakulam; and the 1st Triennale of World Art at Lalit Kala Akademi, New Delhi. Internationally, he had showings at several important events and venues; these included Lugano, Venice, São Paulo, Amman, New York, Warsaw and London. In 1960 and 1963, Hore won Lalit Kala Akademi’s National Awards for painting and graphics, respectively. Subsequently, in 1984, he was made Professor Emeritus at Kala Bhavana, and in the same year awarded the Gagan-Abani Award in Kolkata. Lalit Kala Ratna Puraskar in 2004, the last award he received while alive, capped his full and long journey. The highest recognition for Hore’s work, however, came a year after his death in 2006, in the form of the Padma Bhushan that was posthumously awarded to him in 2007.

First Published: April 21, 2022

Last Updated: July 26, 2023