The British Annexation of Burma

1885–1896

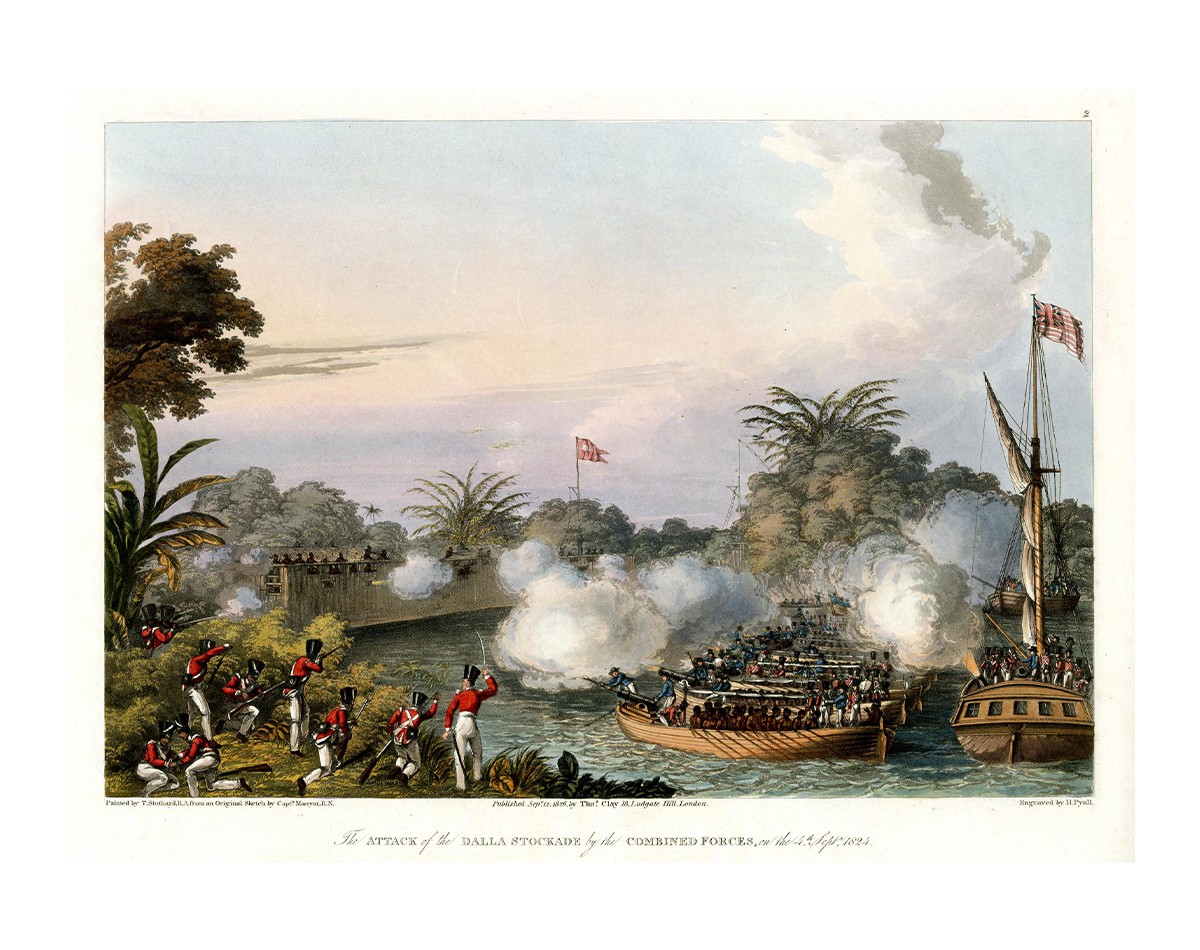

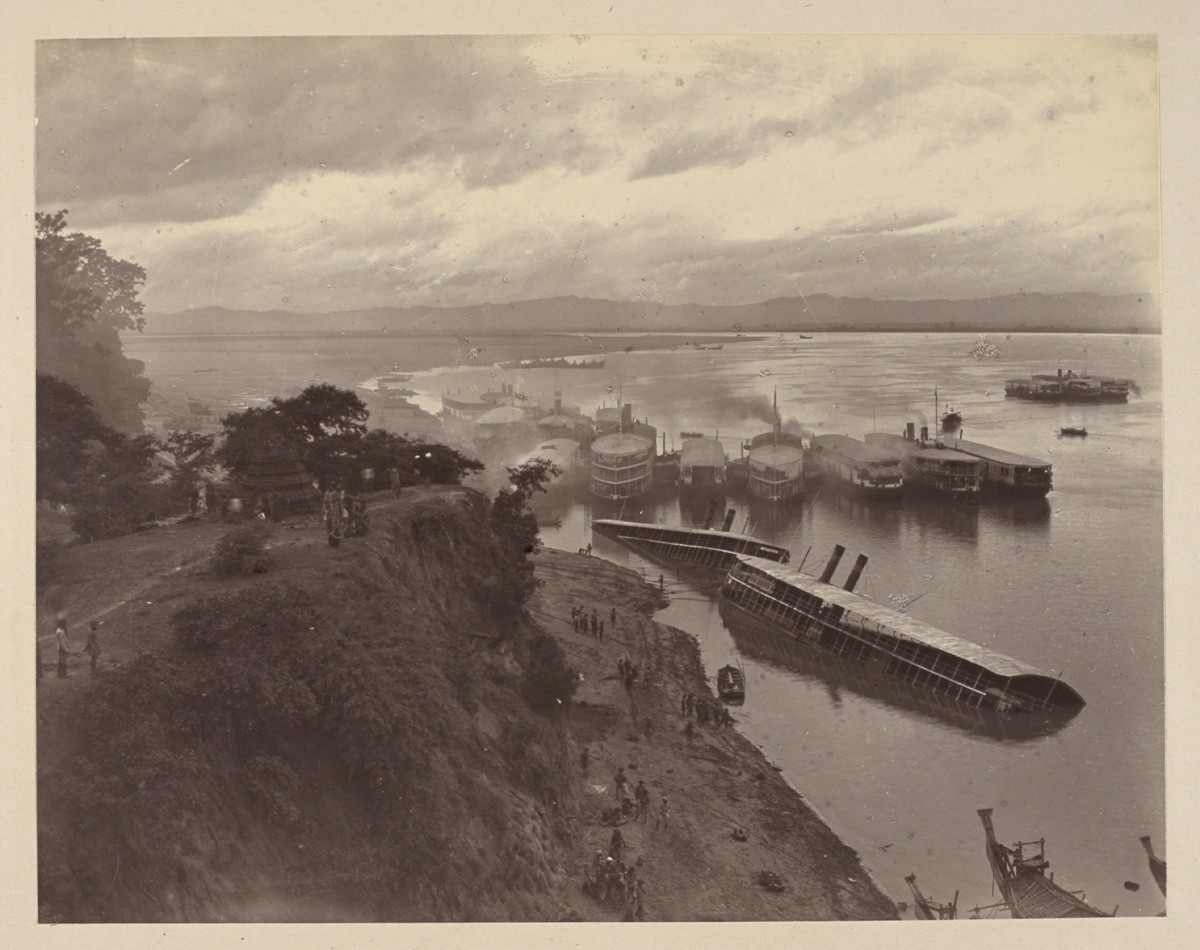

Prompted by British commercial interests and instability within the Burmese monarchy, the Third Anglo-Burmese War takes place in 1885. Two previous conflicts, the First (1824–26) and Second Anglo-Burmese War (1852), have already culminated in the British acquisition of the regions of Arakan (present-day Rakhine), Tenasserim (present-day Tanintharyi) and Pegu (also called Lower Burma).

In the fifty years since the signing of the Treaty of Yandabo in 1826, the British government in India has controlled a large portion of the Burmese coastline, monitored the political and administrative activity in Burma through their British Resident, and collected a heavy indemnity for the First War, effectively crippling the Burmese economy.

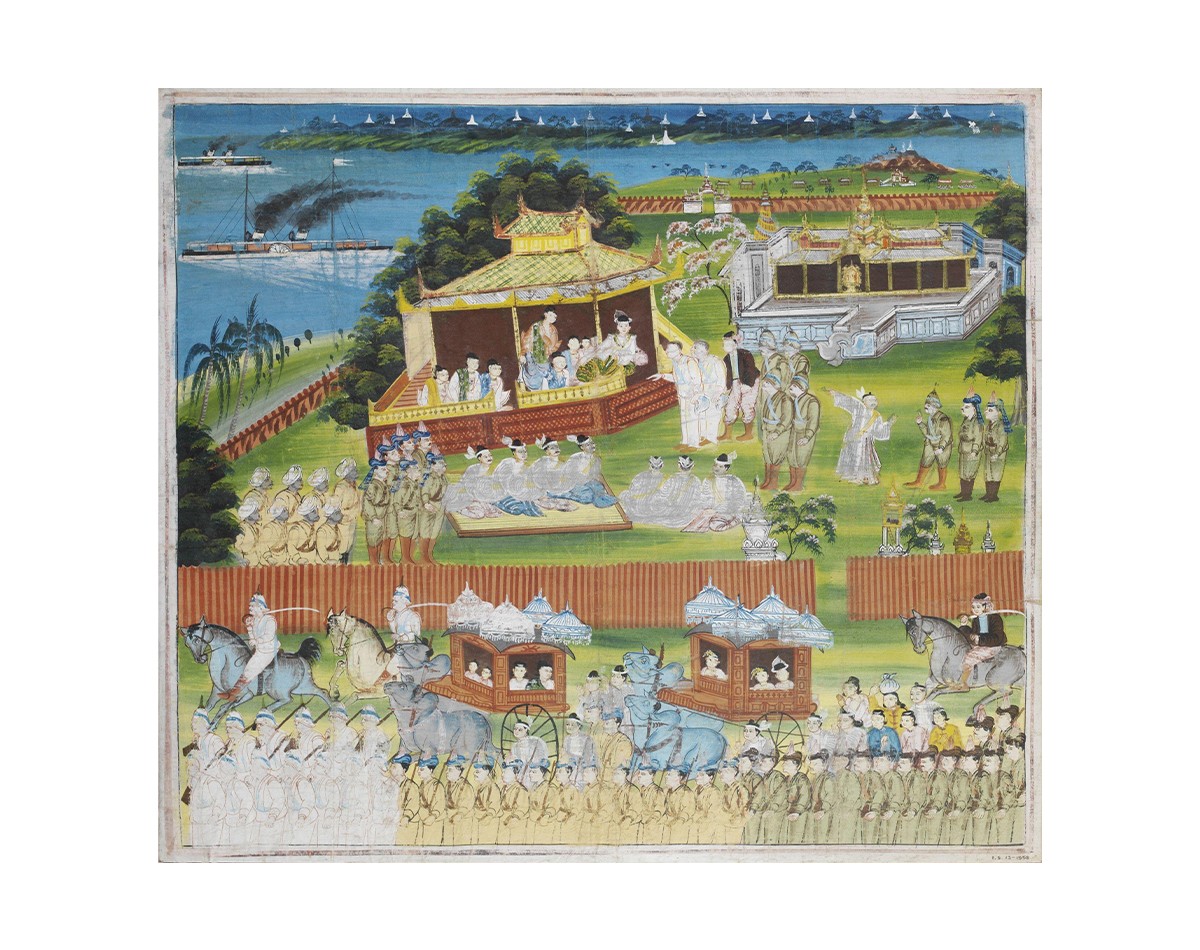

A succession dispute within the Konbaung dynasty and subsequent executions at the royal court in 1878 have made the British government uncertain about the safety of its citizens within Burmese borders. Following the natural death of the British Resident at Mandalay in 1879, therefore, the office has been dissolved. Despite efforts from both sides to come to an agreement on trade and political relations over the next three years, hostilities have remained, with no new treaties signed.

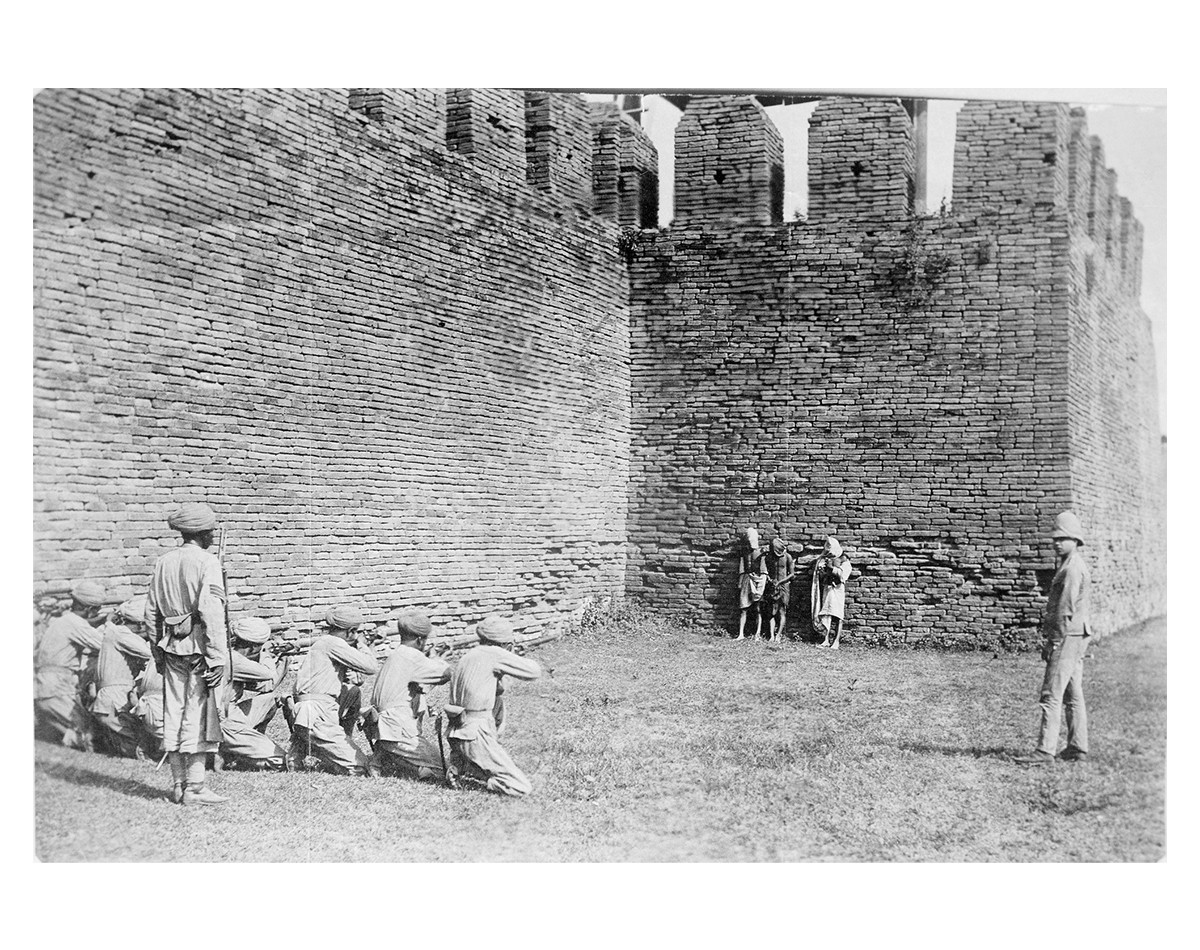

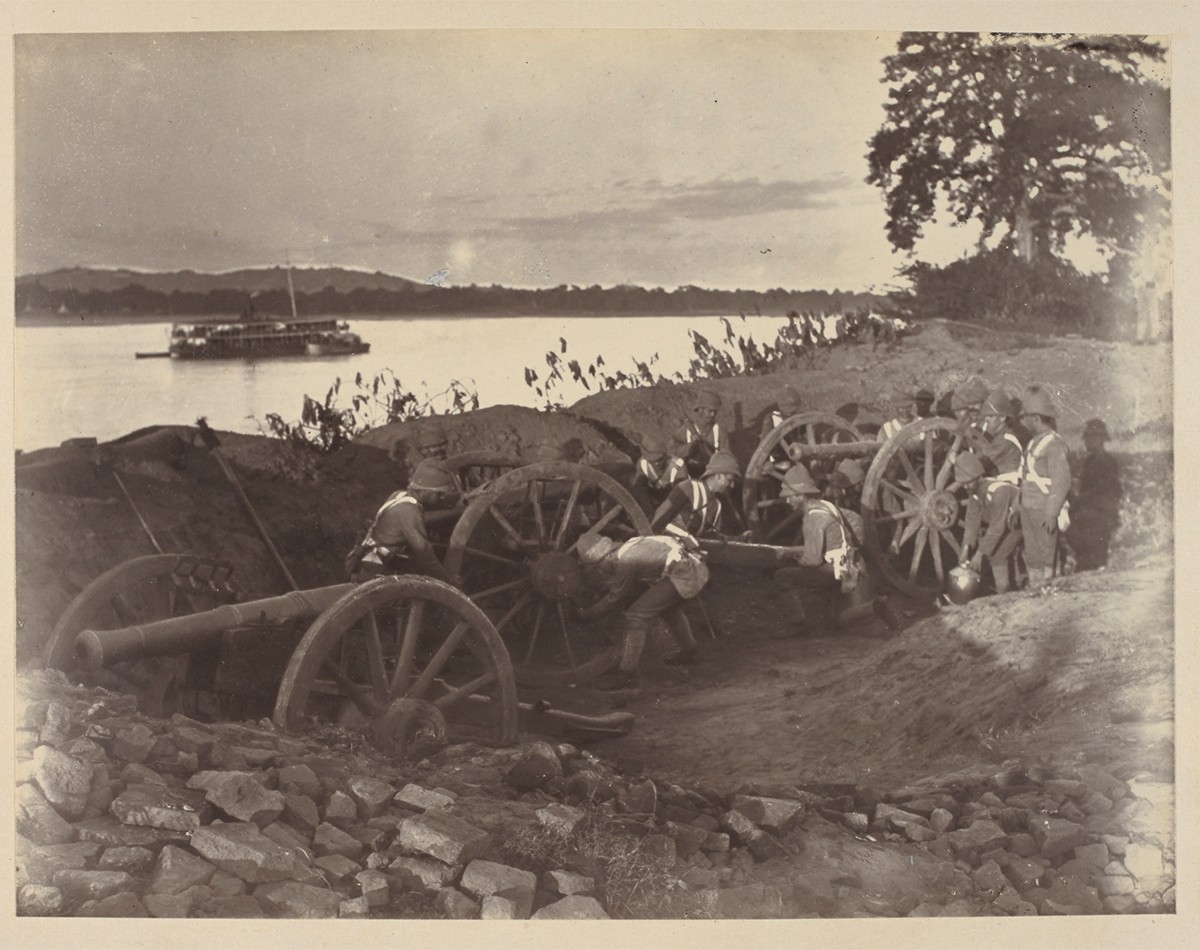

On the pretext that the Burmese court has been secretly purchasing arms from France and has unjustly sued a corporation in Bombay (now Mumbai, India) over a purchase of timber, the British government offers an ultimatum that would effectively place the Burmese royal family and the country’s economic policy under British control. Ignoring the Burmese counter-proposal, British forces begin a military campaign in November 1885. They face almost no resistance due to a lack of loyalty to the king, coupled with various rumours about a British plan to replace the king with a more popular prince. British forces accordingly capture Mandalay quickly, annexing Upper Burma and completing colonial dominance by the end of the month. King Theebaw is made to abdicate and the royal family is exiled to India, signalling the end of the Konbaung dynasty and the Burmese monarchy in general. Scholars today speculate that among the government’s unstated motivations for the war was acquiring access to resources over which the Burmese court had a royal monopoly, namely teak forests, oil wells and jade mines, the products of which would enable British merchants to broaden their trade with China.

Post-annexation, a number of guerrilla resistance movements emerge, led by several princes and nobles across Burma, as well as a number of indigenous groups living in forests and other remote parts of the country, such as the Chin. However, the disorganised attacks struggle to challenge British control effectively, and are quelled by 1896.

Bibliography

Aung, Maung Htin. A History of Burma. New York: Columbia University Press, 1967.

Aung, Maung Htin. The Stricken Peacock: Anglo-Burmese Relations 1752–1948. The Hague: Springer Netherlands, 2013.

Myint-U, Thant. The River of Lost Footsteps: Histories of Burma. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006.

Feedback

This entry appears in

Art in South Asia

Visit Timeline

Associated Timeline Events

First Published: March 11, 2024

Last Updated: August 5, 2024