The Colombo Museum Is Built

1873–1877

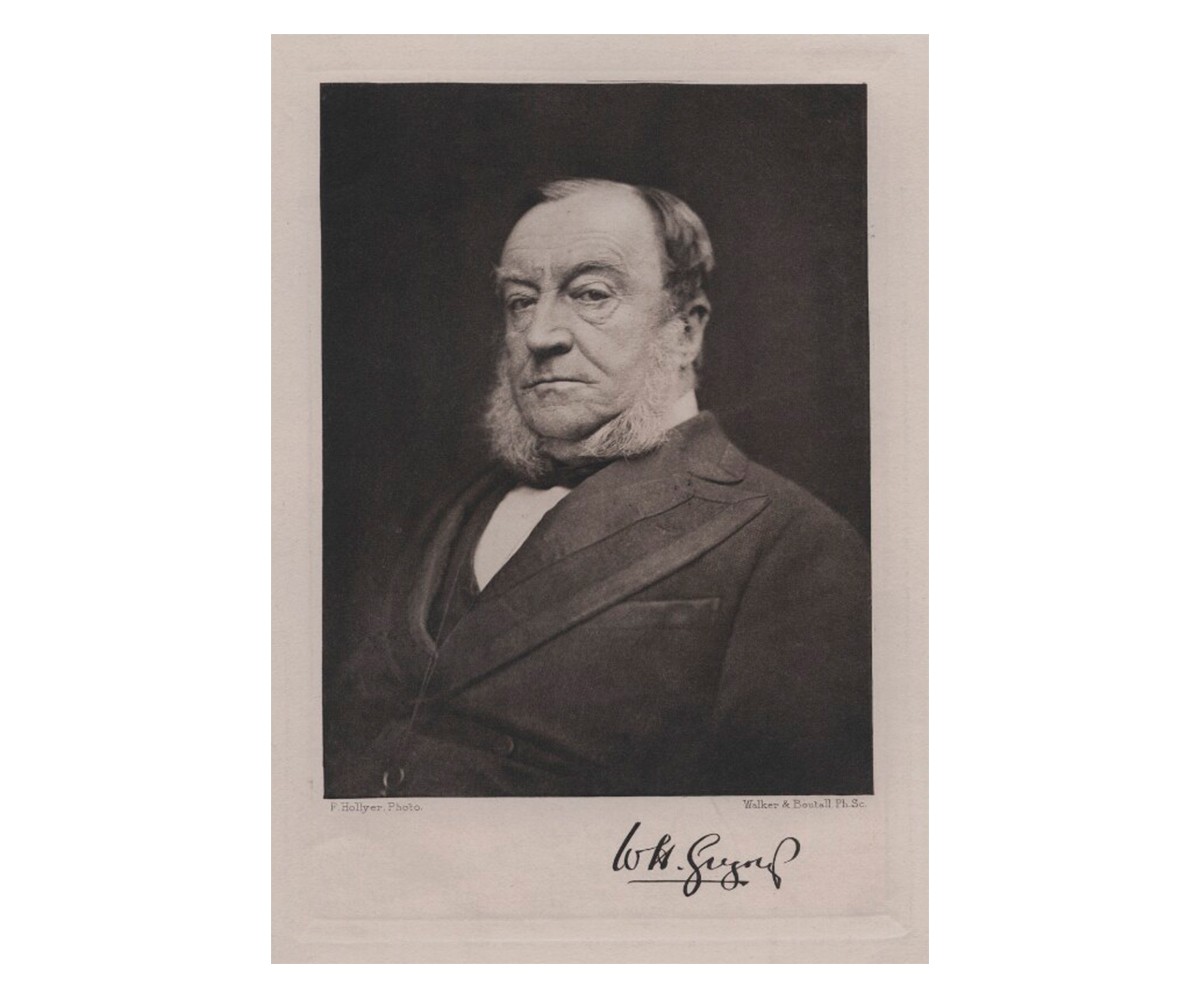

The first museum of British Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka) — today known as Colombo National Museum — is constructed in its capital. It is to house the island’s ancient and medieval artefacts, crucial to the growing body of scholarship on its natural and cultural history, which have so far been housed in the Royal Asiatic Society’s office in Colombo. In 1873, the British governor William Henry Gregory’s proposal to build a museum to house the collection — and thereby make space for the Society’s expanding library — is approved. The museum is built over the next three years, opening on January 1, 1877.

Designed by architect James C Smither and built under the supervision of SM Perera and Wapchi Marikkar, the building is an example of Neoclassical architecture, a popular style for public buildings in nineteenth-century Europe, and is distinctive for its Palladian windows on both storeys. Significantly, a hybridisation of local and European styles is not attempted here as it is with Indo-Saracenic buildings in India, such as the Government Museum in Madras (present-day Chennai).

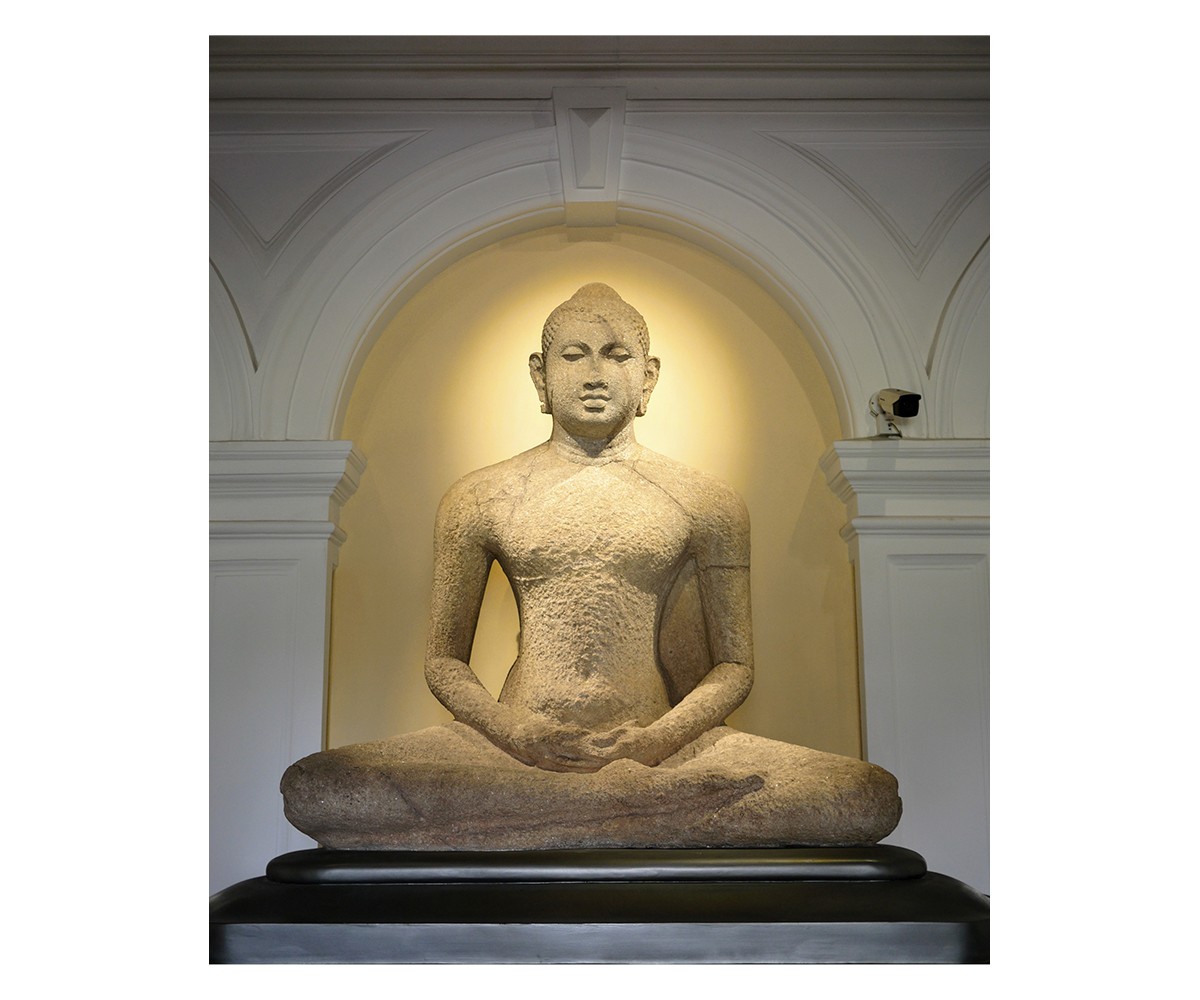

Beyond its physical form too, at its inception, the museum is an emphatically colonial project, with exclusively European administrative staff and an English-language journal called Spolia Zeylanica, literally meaning ‘Spoils of Ceylon’. Over subsequent years, however, the museum — like many other institutions of colonial origin — will be reclaimed by the country, coming to reflect Sri Lankan history better. In particular, the collection will grow to include several artefacts connected to the Relic of the Buddha’s Tooth, such as the remains of elephants who carried the Tooth in Kandy’s annual Esala Perahera festival, and artefacts that suggest the extent of the island’s pre-colonial influence on global trade and politics, such as the the fifteenth-century Trilingual Inscription left by the Chinese admiral Zhang He, engraved in Tamil, Mandarin and Persian. Today, the museum also houses important repatriated artefacts — most notably the Kandyan throne, taken by British forces in 1815 and returned in 1934 — and replicas of objects that either could not be acquired, such as the seventh-century gilt bronze statue of Tara housed at the British Museum, and others that have since been destroyed, such as some of the Sigiriya murals.

Bibliography

Dewaraja, Lorna. “Cheng Ho’s Visits to Sri Lanka and the Galle Trilingual Inscription in the National Museum in Colombo.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Sri Lanka 52, no. 1 (2006): 59–74. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23731298.

Kiribamune, Sirima. “Tara, a Replica.” Digital Library for International Research Archive. Accessed December 21, 2023 http://www.dlir.org/archive/items/show/12502.

Perera, Janaka. “National Museum: Looking Back 130 Years.” Sunday Observer, January 14, 2007. Accessed December 20, 2023. https://archives.sundayobserver.lk/2007/01/14/fea10.asp.

Raheem, Ismeth. “The Dutch Came Bearing the Kandyan Royal Throne!” Sunday Times, June 28, 2020. Accessed December 20, 2023. https://www.sundaytimes.lk/200628/plus/the-dutch-came-bearing-the-kandyan-royal-throne-407500.html.

Salie, Ryhanna. “National Museum: Window into the Past.” Sunday Observer, February 25, 2018. Accessed December 20, 2023. https://archives1.sundayobserver.lk/2018/02/25/heritage/national-museum-window-past.

Feedback

This entry appears in

Art in South Asia

Visit Timeline

Associated Timeline Events

First Published: March 11, 2024

Last Updated: July 2, 2024