The Indigo Revolt in Bengal

1859

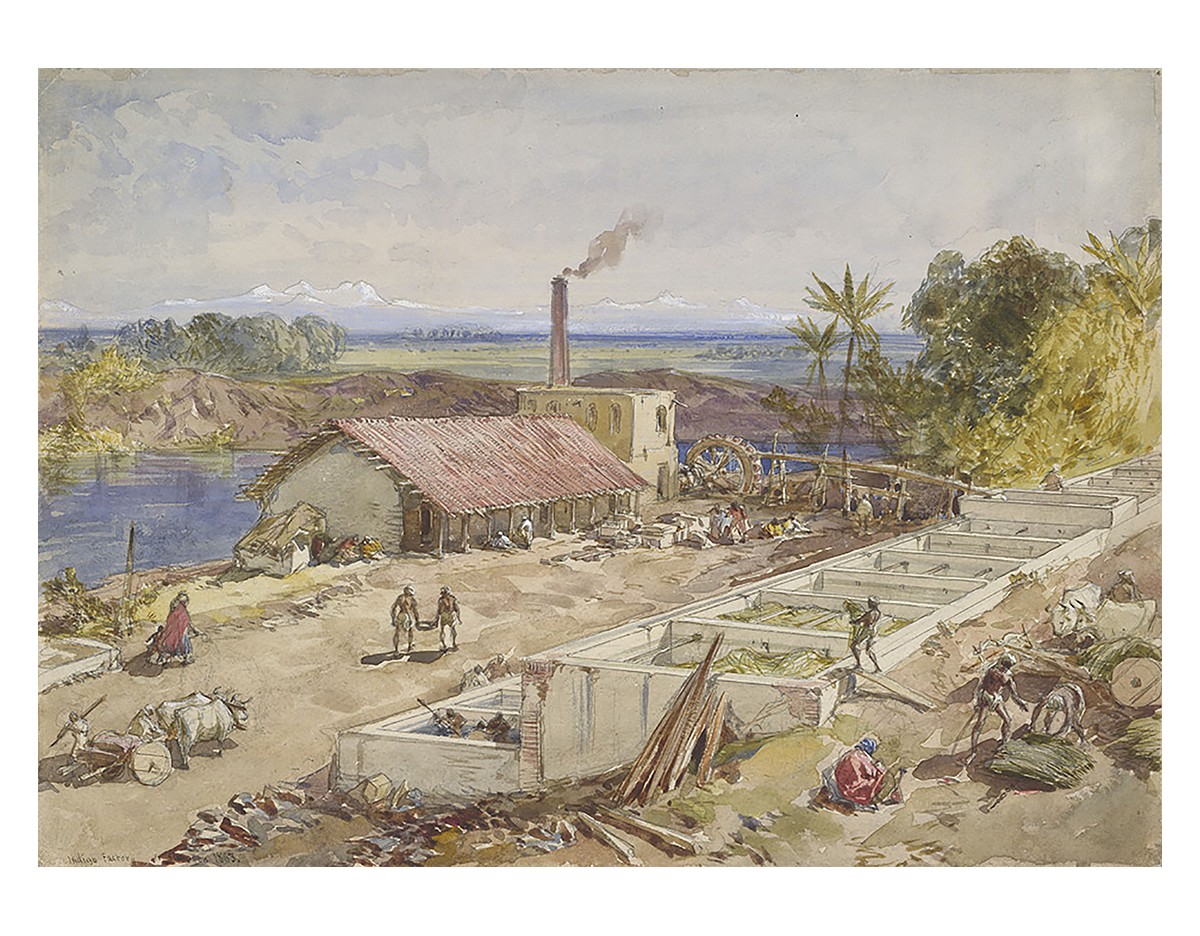

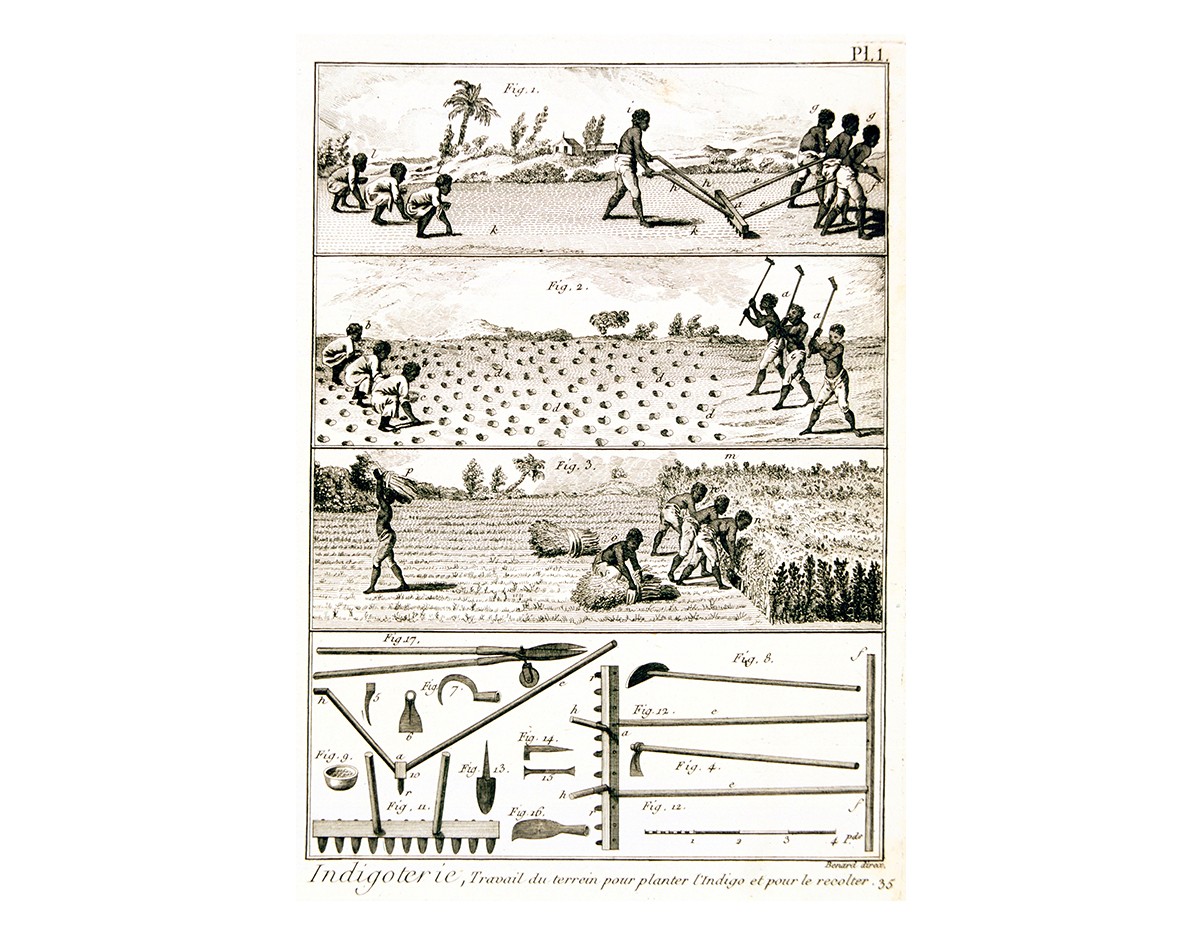

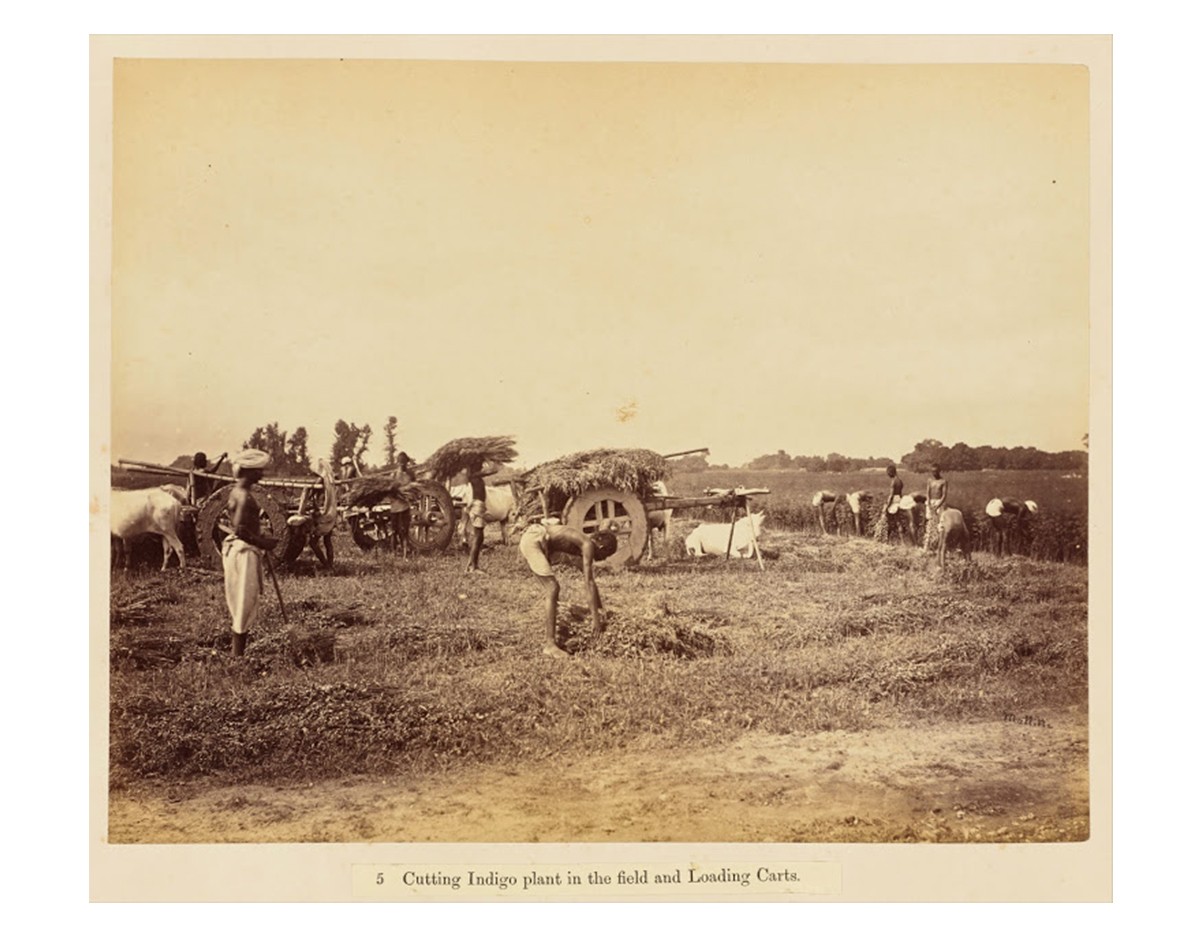

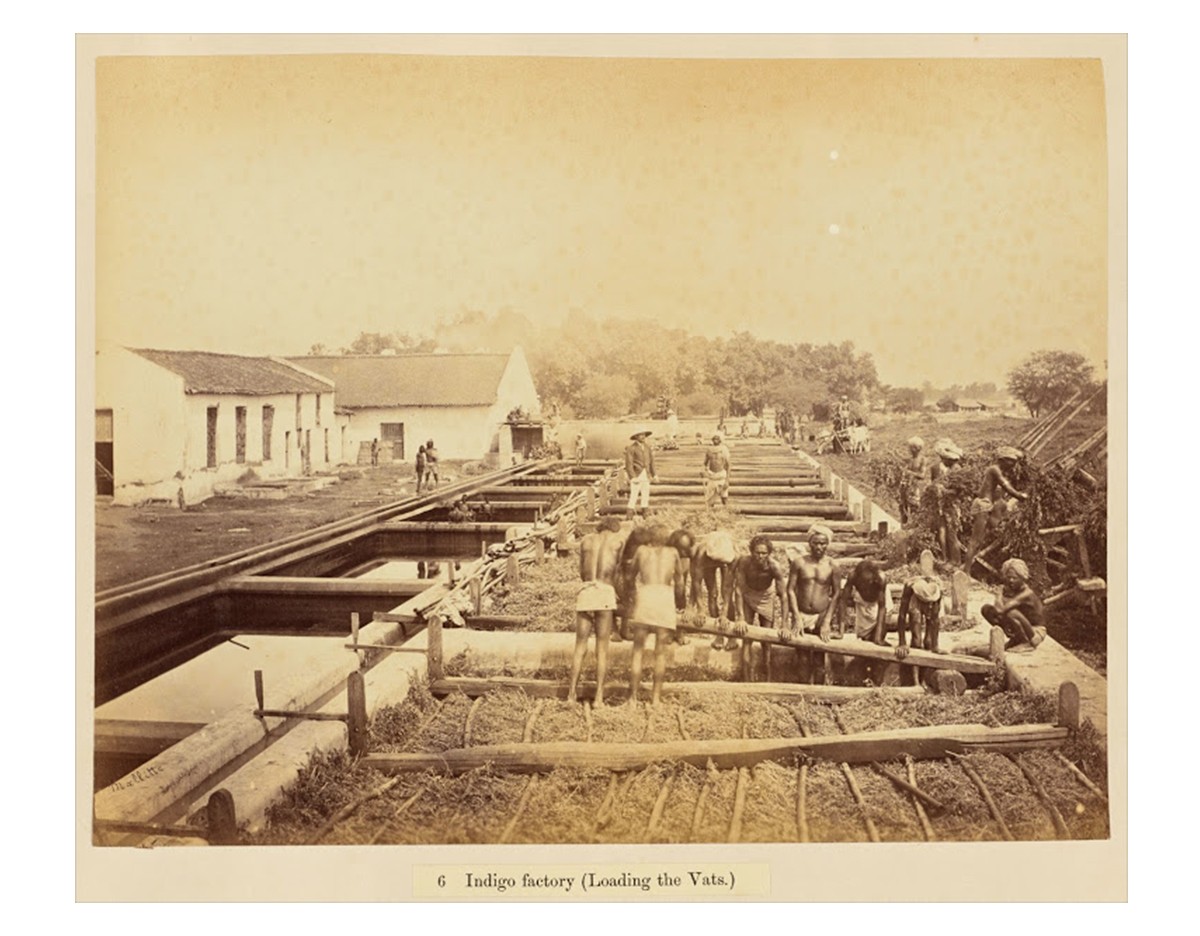

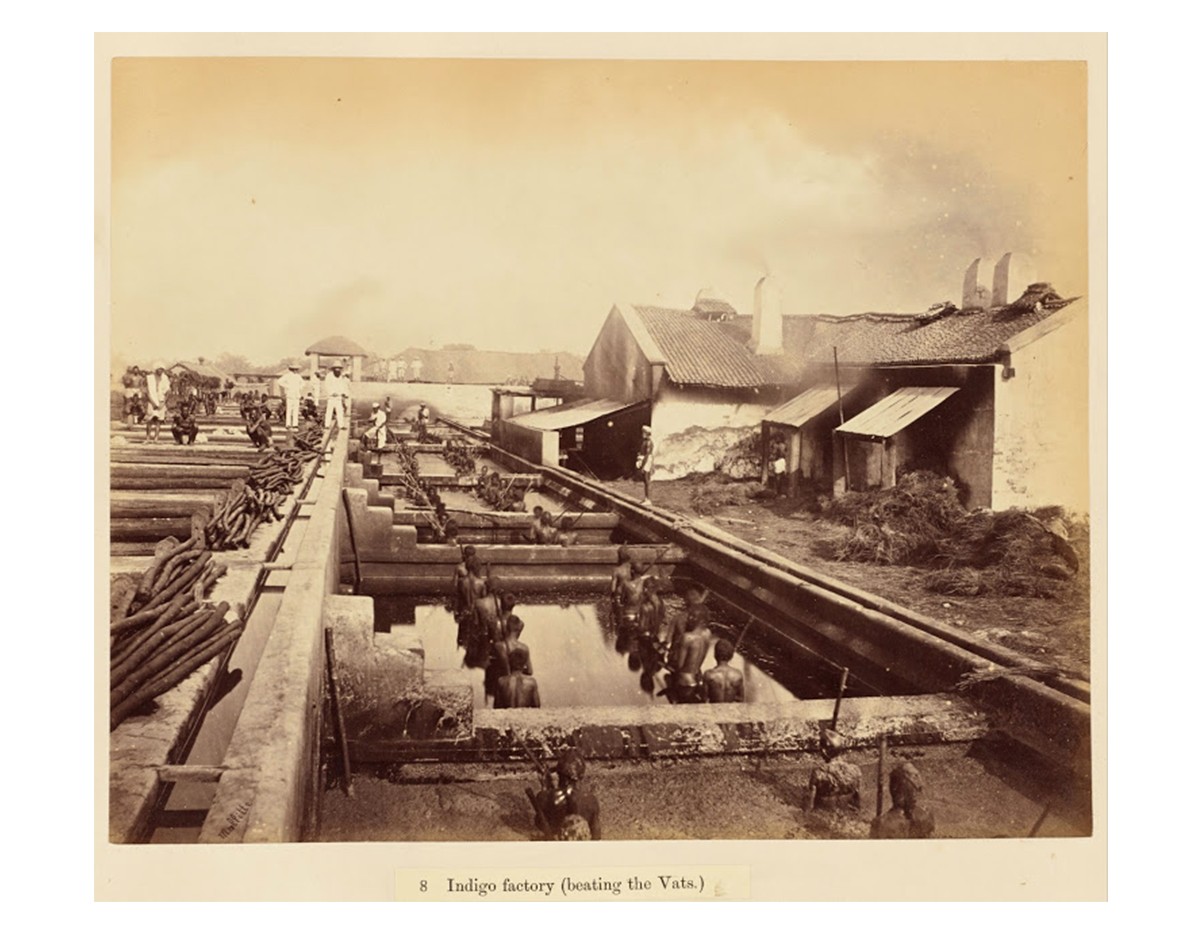

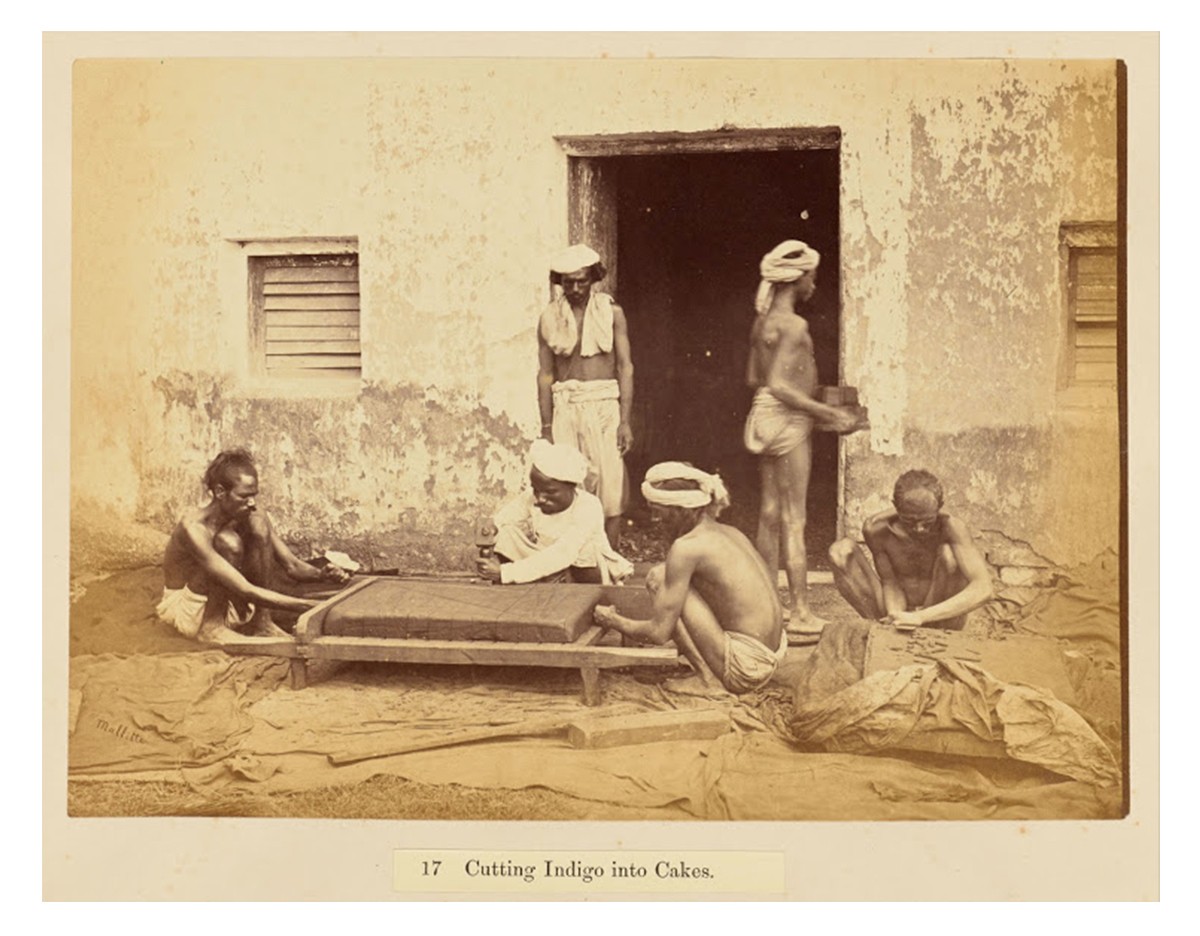

From 1757, the British East India Company’s Tinkathia (Hindustani for ‘three kathas’) system made it mandatory for planters (landowners) to grow indigo on at least three kathas (a unit of land measurement) in each bigha (1 bigha = 20 kathas) of their land, for export to Europe. Landowners enlisted the services of ryots or tenant farmers, who were often made to cultivate indigo (historically a crop not grown in Bengal) instead of food crops. While landowners and British traders made considerable profits, the workers were compensated poorly and forced into debt, sometimes even starvation.

The Indigo Revolt of 1859 is the first major uprising by indigo farmers against landowners and indigo traders, and not exclusively the colonial government. Beginning with the Nadia district and spreading to other areas of the Bengal Presidency (which spanned the northern and eastern regions of South Asia), farmers refuse to continue cultivating indigo. While the revolt itself is non-violent, the response enacted by the landowners is — they file lawsuits and often hire mercenaries to attack farmers after production slows. In March 1860, the British colonial government passes the Indigo Act which guarantees farmer contracts for another season, and appoints the Indigo Commission to investigate cultivation practices. The findings of the Commission confirm the poor working conditions of the farmers and the exploitative practices of the planters.

Bibliography

Gilon, Catherine. “Indigo: The Story of India’s ‘Blue Gold’.” Al Jazeera, December 13 2020. Accessed October 12, 2023. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2020/12/13/indigo-and-the-story-of-indias-blue-gold.

Kumar, Prakash. Indigo Plantations and Science in Colonial India. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Nadri, Ghulam A. The Political Economy of Indigo in India, 1580-1930: A Global Perspective. Boston: Brill, 2016.

Feedback

This entry appears in

Art in South Asia

Visit Timeline

Associated Timeline Events

First Published: March 11, 2024

Last Updated: August 5, 2024