The Revolt of 1857

1857–1859

The Indian Revolt of 1857, known variously as the Sepoy Mutiny or 1857 Rebellion, erupts as a result of both immediate and long-standing grievances against British rule in India. Immediate triggers include the use of new Enfield rifle cartridges greased with beef and pork fat for the British East India Company’s (EIC) army, which offends the religious sentiments of Hindu Brahmins and Muslim soldiers respectively. The Indians’ broader resentment stems from British policies that systematically undermine traditional Indian institutions, religious beliefs and social structures, as well as economic exploitation through annexation, indirect governance and heavy taxation on staple goods, which alienates the Indian elite as well as the masses.

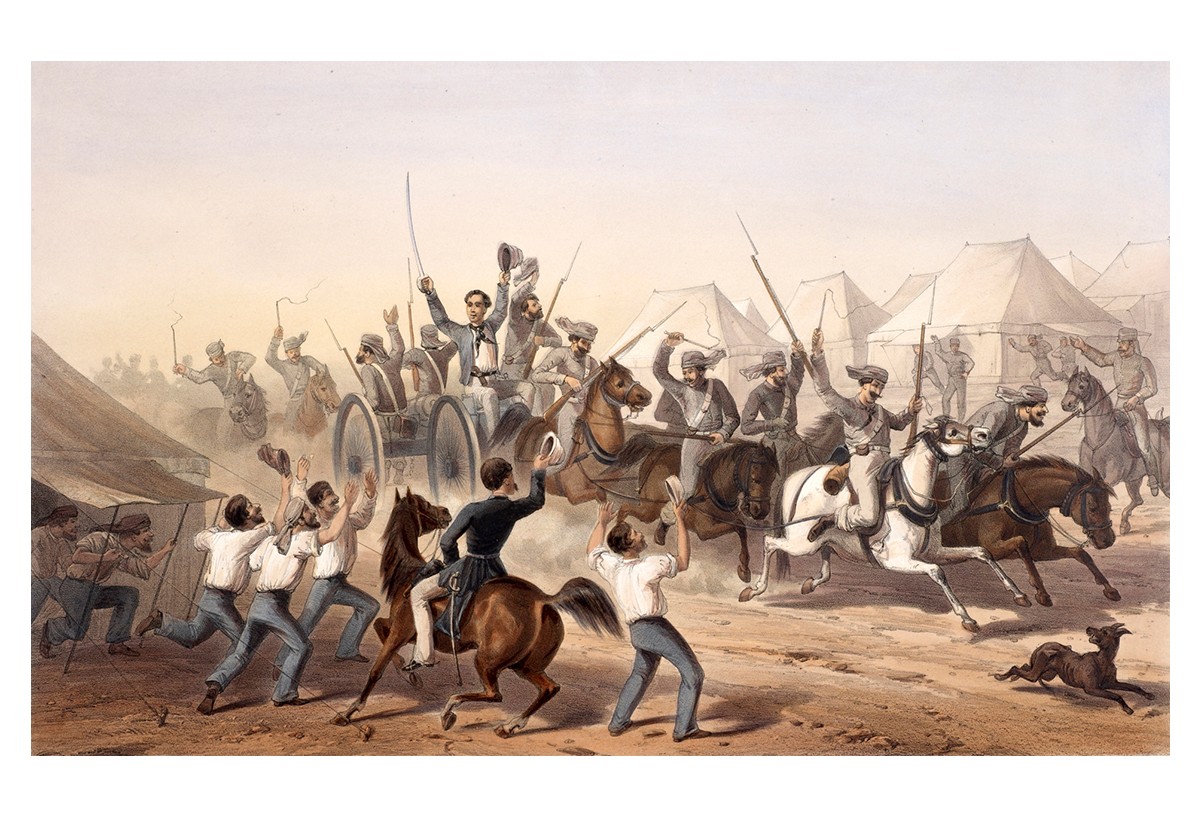

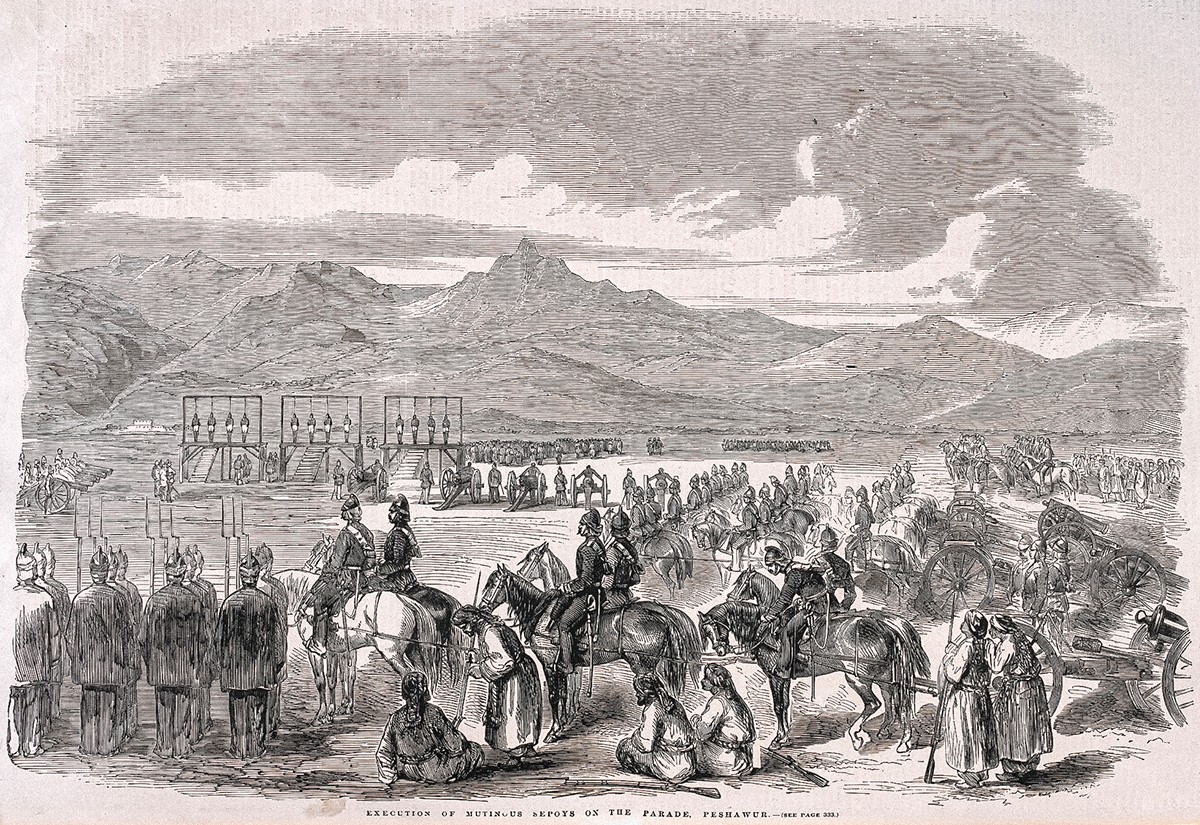

The military revolt spreads across large sections of northern and central India, primarily at urban centres such as Delhi, Kanpur, Lucknow and Jhansi, as well as rural areas, and key figures emerge as symbols of resistance. Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi, Nana Sahib of Kanpur and Bahadur Shah II, the last Mughal emperor, play pivotal roles in rallying rebels against British rule, either leading by example or serving as figureheads for the movement. After months of fighting, British forces take back the various areas temporarily held by the rebels, and the movement’s leaders are either executed or exiled. The following year, the British Crown formally takes over the administration of India through the Government of India Act of 1858, as the EIC is seen as unfit to continue the task.

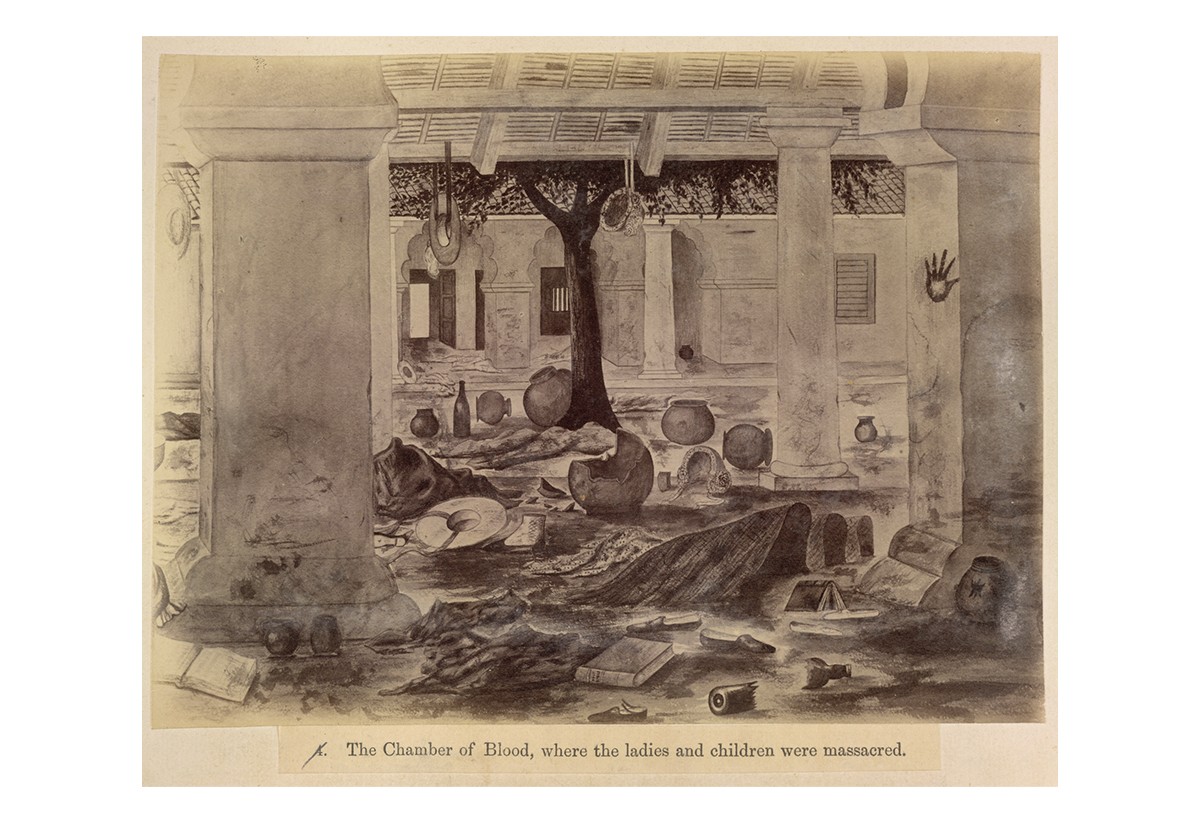

Among other things, rumours about the rape and murder of British women in cities taken over by the rebels — despite the lack of corroboration from any survivors — are used by the British to justify a swift and aggressive suppression of the revolt.

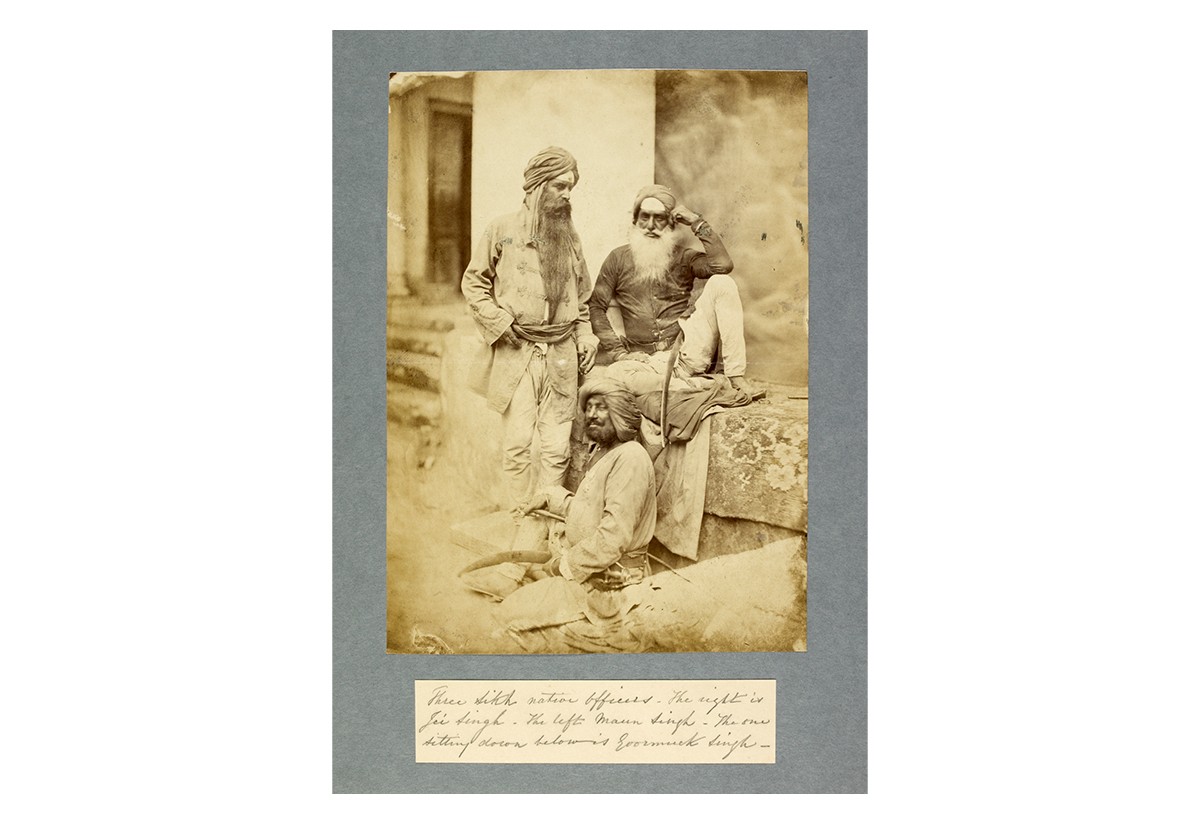

War photography is also used to considerable effect to portray the rebels as cruel and violent. Lord Canning, the then Governor-General of India, employs John Murray to take photographs of the revolt, with specific instructions to highlight the Indian sepoys’ disobedient and anarchic nature. In early 1858, Felice Beato, an Italian photographer, takes the help of army officers to record scenes from the aftermath of the uprising at the major staging points of Delhi, Agra, Lucknow and Kanpur. He sometimes composes images at these sites in ways that seem to celebrate war, driven both by the need to recreate the scenes of battle, particularly the defeat of the enemy — in one instance, even using exhumed human remains — as well as a desire to meet the growing commercial appeal of high drama among his Western viewership.

Bibliography

Chari, Mridula. “Haunting Images of India’s 1857 Uprising Against the British, Shot by Felice Beato.” Scroll.in, June 25, 2014. Accessed September 26, 2023. https://scroll.in/article/666129/haunting-images-of-indias-1857-uprising-against-the-british-shot-by-felice-beato.

Chaudhary, Zahir R. Afterimage of Empire: Photography in Nineteenth-Century India. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Desmond, Ray. “Photography in Victorian India.” Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 134, no. 5353 (December 1985): 48–61.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/41374078.

Doniger, Wendy. The Hindus: An Alternative History. New Delhi: Speaking Tiger, 2009.

Gaskell, Nathaniel, and Diva Gujral. Photography in India: a Visual History from the 1850s to the Present. Munich: Prestel Publishing, 2018.

Lothspeich, Pamela. “Unspeakable Outrages and Unbearable Defilements: Rape Narratives in the Literature of Colonial India.” Postcolonial Text 3, no. 1 (2007). https://www.postcolonial.org/index.php/pct/article/viewFile/604/402.

Feedback

This entry appears in

Art in South Asia

Visit Timeline

Associated Timeline Events

First Published: March 11, 2024

Last Updated: May 22, 2024